Twitter

Facebook

LinkedIn

Reddit

WhatsApp

It is a statement of the obvious but unless a force can move to where it is needed, it cannot be of much value.

Deployability is an essential component of capability and deterrence.

Deployability is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as

(of soldiers and equipment) able to be moved to a place where they can be used when they are needed

Soldiers and equipment need vehicles for the most part, and so vehicle mobility is a key building block of deployability. If a vehicle is too large or heavy to use a particular mode of transport it may be of less use to operational leaders and provide decision-makers with fewer options.

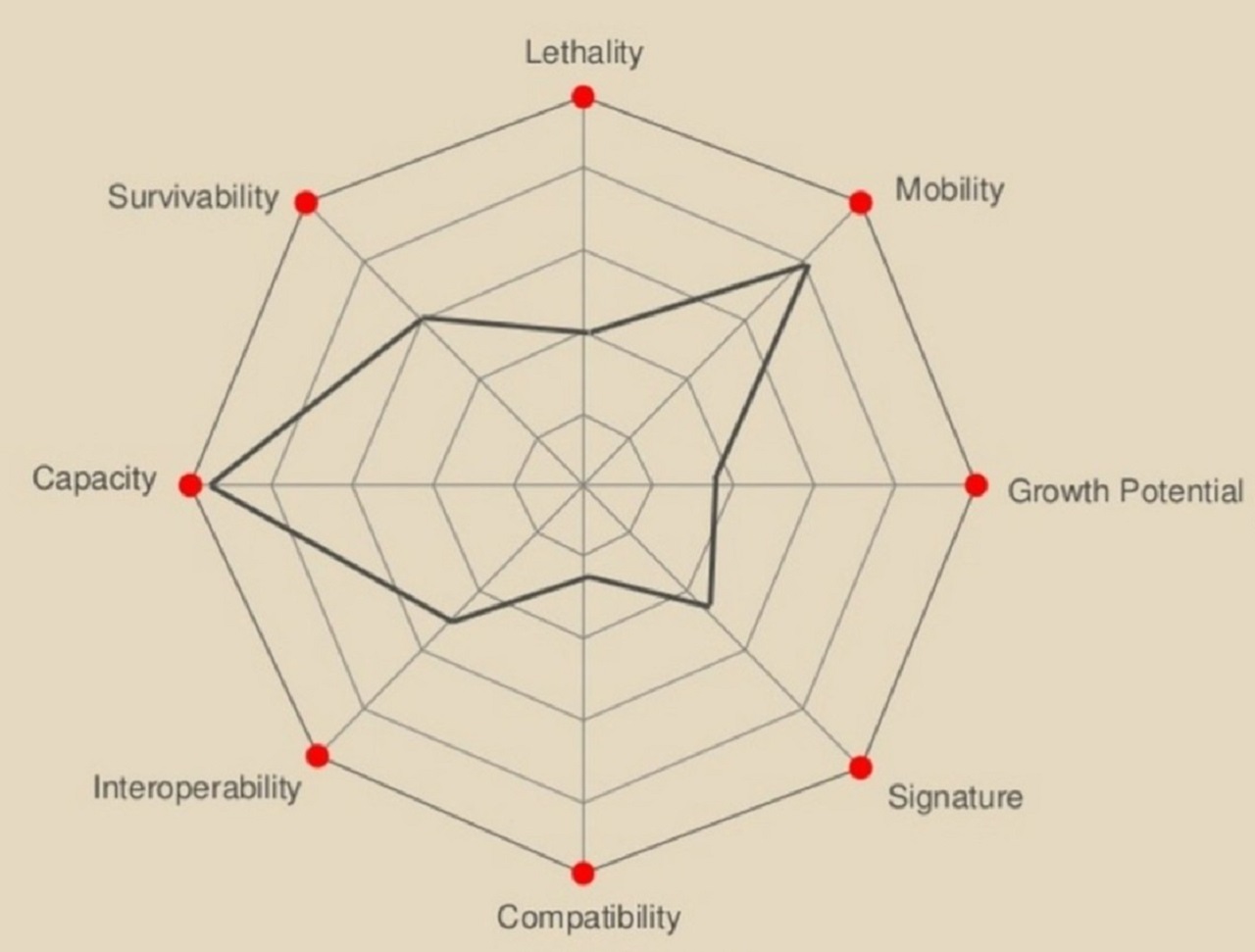

Vehicle designers fully understand the compromises inherent in meeting requirements.

Mobility can be further broken down by category, ground pressure, turning circles, fuel consumption, gap crossing, approach and departure angles, traction, flotation, fording ability, or the hundreds of other design criteria that determine a vehicle’s strategic and operational mobility.

For this article, I am going to consider transportability.

Transportability is the inherent capability of materiel and units to be moved efficiently by existing or planned transportation assets

Transportability is important for everything from light role infantry to armoured.

There is little point in having a rapid deployment force whose main feature is the ability to exploit the speed and reach of air power if its vehicles and equipment are too big or heavy to use the most common aircraft readily available to it.

A main battle tank is no good sitting in a storage shed if there are no trailers to move it from there to where the enemy might be or is.

Wilfred Owen makes a good argument for transportability in a 2016 RUSI Journal article

Much of the discussion on mobility has been hampered by the way the concept has been understood. Western military doctrine and academic studies have tended to address mobility in three categories: strategic; operational; and tactical. In other words, conventional conceptual understanding of mobility is strongly aligned to the levels of war. This way of thinking is not fit for purpose. As such this article proposes four alternative categories; transportability, marching, obstacle-crossing and protection as a more appropriate lens through which to understand the idea of mobility.

Transportability is defined here as the ability to move a unit, formation or force in or on other vehicles, such as ships, aircraft, rail or road vehicles (transporters). Marching is the ability to move long distances by road at an effective speed and with relative security. Obstacle-crossing is the ability of individual vehicles to surmount a set series of obstacles or move over various surfaces and inclines. That may include amphibious capabilities.

It doesn’t matter whether we are talking about an e-bike or an MBT, they are virtual ‘loading gauges’ they must pass through in order to be useful. Transportation and the built environment will determine what these loading gauges look like.

Whilst we can mostly define transportability in terms of weight and dimensions, as with many similar subjects, it is more complicated than that. Axle weights, G loading and tie-down arrangements are just three subjects that will influence whether vehicle A can travel inside Vehicle B.

This article is therefore hugely simplified, it only considers weight and dimensions.

Whether land, sea or air, transport assets have limits.

Transport Aircraft

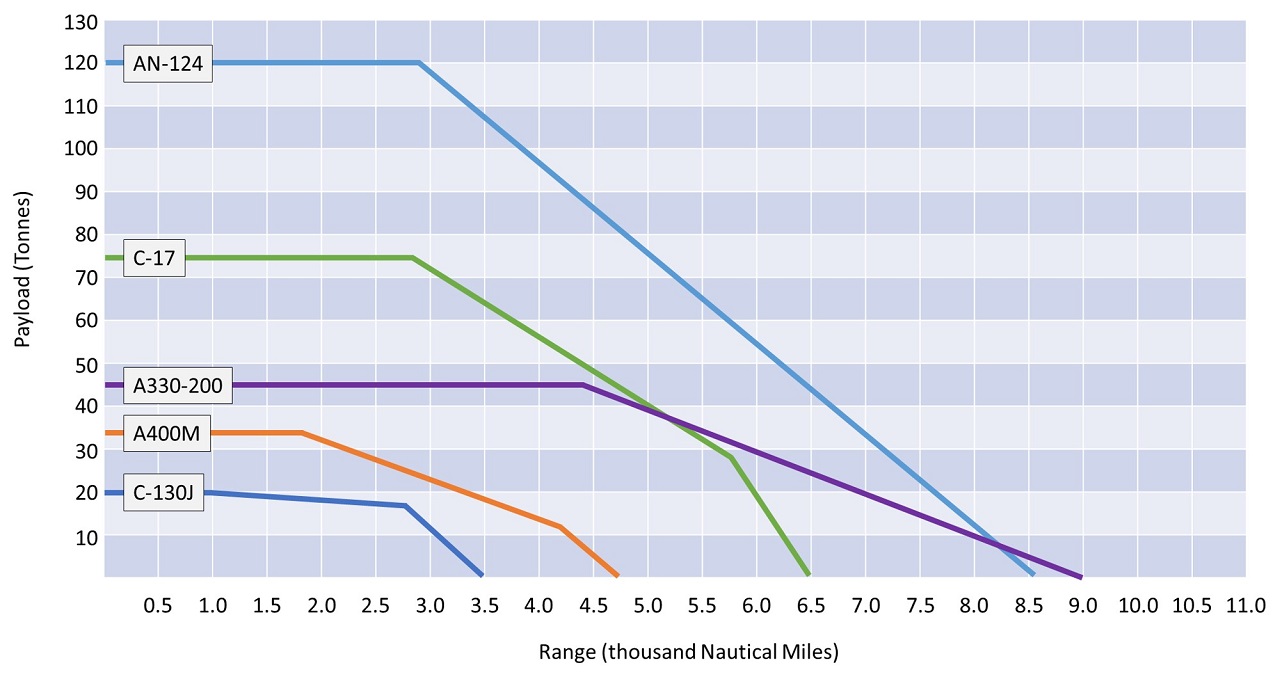

The closer the aircraft gets to its maximum payload, the more performance (especially range) will be reduced.

When we talk of vehicle weights we must also talk about aircraft range/landing altitude and consider what might be ‘normal’ weights, not theoretical maximums in the brochures.

The maximum payload of the A400M Atlas objective was 37 tonnes. For planning purposes, I would tend to a figure of 30-32 tonnes, compared to 15-16 tonnes for a C-130J. Likewise, with the C-17, a more sensible figure to use is 60-65 tonnes rather than the absolute maximum.

Even with these weight limits, there are many factors that might reduce the actual cleared figure; weight distribution, floor loading limits, uniformity of shape, securing practice and safety considerations for example.

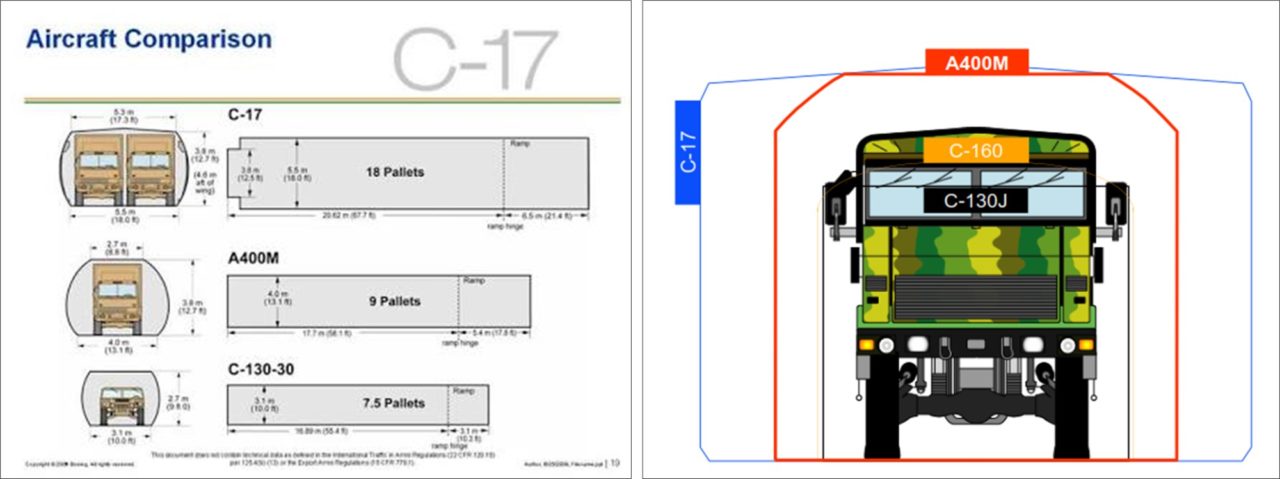

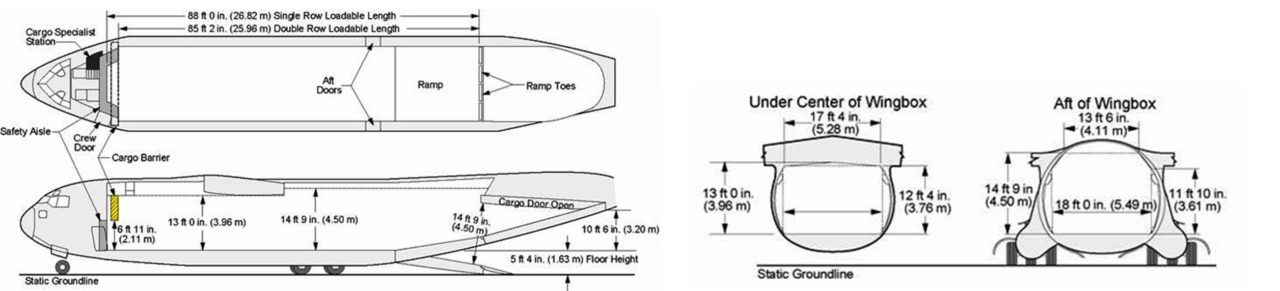

Cargo hold dimensions are a limiting factor for many vehicles.

Not all aircraft have a uniform roof height or cargo bay width, the wing box or landing gear may impinge and reduce height for some parts of the aircraft, the C-17 being a good example of this.

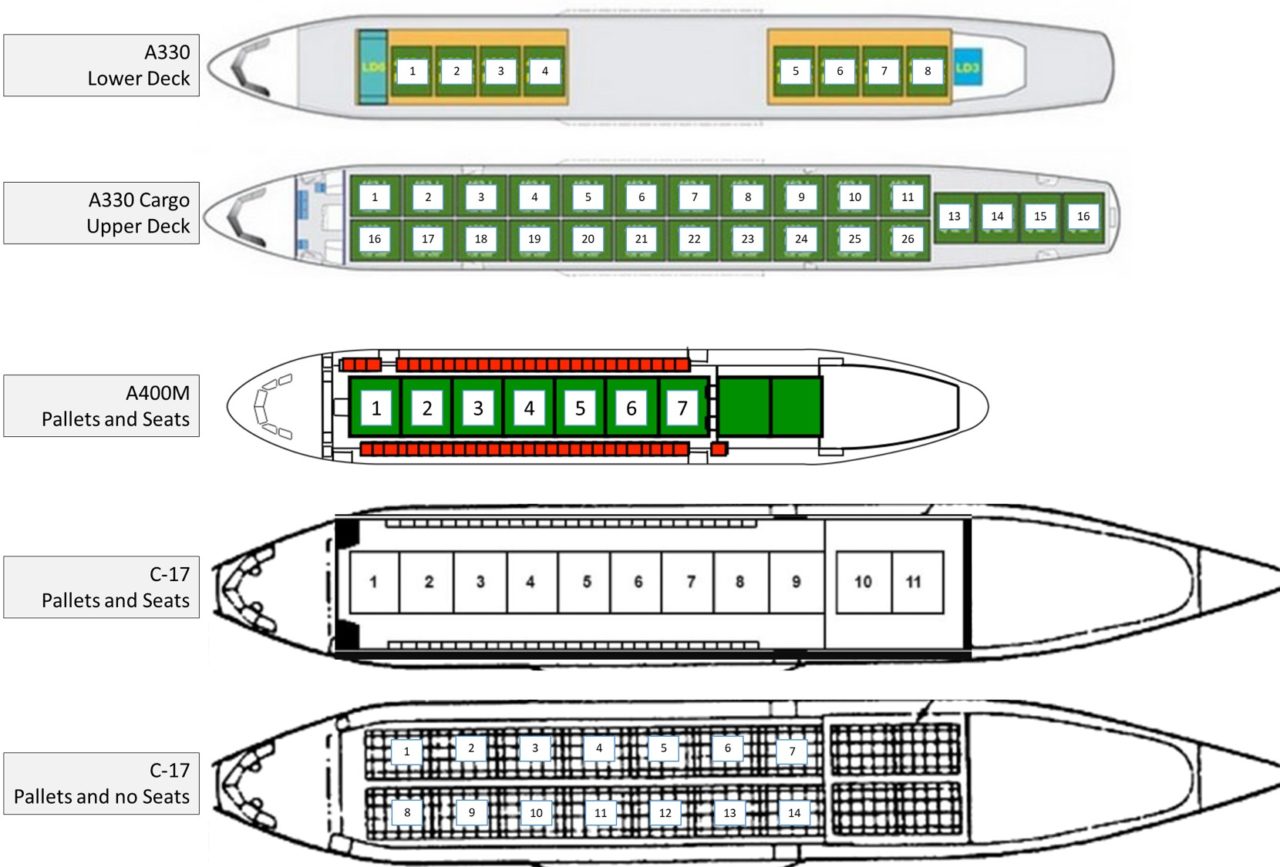

For some vehicles and aircraft combinations, not exploiting the full allowable width will allow personnel seating to be used at the same time. The image below shows an A400M configured with and without seating.

Aircraft ramp areas can also be utilised as overhang space in some configurations, this is a fantastically complex subject but as a rule of thumb, the following might be considered.

| Aircraft | Width | Height | Length | Sensible Max Payload |

| C-130J | 3.12m | 2.74m | 12.1m | 15-16 tonnes |

| C-130J-30 | 3.12m | 2.74m | 17.0m | 15-16 tonnes |

| A400M | 4.00m | 3.85m | 17.7m | 30-32 tonnes |

| C-17 | 5.50m | 3.80m | 19.9m | 60-64 tonnes |

| AN-124 | 6.60m | 4.40m | 36.0m | 90-100 tonnes |

Packing density is important for inter-theatre lift and given a finite number of aircraft sorties available in a given time period, it will determine the force build-up speed when utilising aircraft.

Helicopter – Internal Carriage

The UK only operates two cargo ramp-equipped helicopters (Merlin and Chinook) but it might also be useful to consider others for reference.

Seat arrangements, differences between the ramp and internal dimensions, ramp break-over dimensions, cargo floor equipment and other internal obstacles might ultimately result in a vehicle not being able to actually fit inside so the dimensions are shown below and indicative only.

| Helicopter | Width (m) | Height (m) | Length (m) |

| Merlin | 2.0 | 1.8 | 6.5 |

| Chinook | 2.1 | 1.9 | 9.3 |

| NH90 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 4.8 |

| Mil 8 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 5.3 |

| CH-53K | 2.7 | 1.9 | 9.1 |

| V-22 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 7.4 |

Carrying vehicles inside a helicopter is always going to be an exercise in compromise but it does have many performance advantages compared to carrying them as an underslung load.

Maximum weights for internally carried vehicles may be somewhat similar to those on the hook, but in many cases will be lower and have specific floor and ramp limits.

Helicopter – Underslung Load

Using helicopters for external loads is quite commonplace, but it is a complex and potentially dangerous business where the limits and operating procedures have evolved over many years.

All UK helicopters (except AH and some training types) have external lift capabilities.

Simply saying X vehicle weighs Y and will therefore be able to be slung load from Z helicopter might not be true, clearance will depend on many factors and in general terms, more weight equals less range, speed or ability to operate at higher altitudes.

The table below shows external load clearances obtained from open-source data and is only indicative.

| Helicopter | Sling Load Clearance (tonnes) | Notes |

| Wildcat | 1.00 | equipped with a Drallim Semi-Automatic Cargo Release Unit (SACRU) No 2 Mark 1 cargo hook with a design load of 1,497kg |

| Puma Mk2 | 2.25 | has a SACRU Number 1 Mk3 with a safe working load of 2,724kg |

| Merlin HC | 4.10 | has a Talon SACRU with a safe working load of 5,443 kg |

| AW149 | 2.80 | |

| Chinook | 11.3 | the centre hook has a safe working load of 11,300kg |

| Mil 8 | 3.00 | |

| NH90 | 4.00 | |

| Blackhawk | 4.08 | |

| CH-53K | 15.90 | |

| V-22 | 6.80 | the single hook is rated at 4,536kg although, with a two hook system, this is increased |

Strops, slings, spreader bars, nets and other equipment fall into the general term of Helicopter Underslung Load Equipment, or HUSLE.

Taken together, these can weigh up to several hundred kilograms so, in addition to operating margins and clearances, it is also important to take these into account.

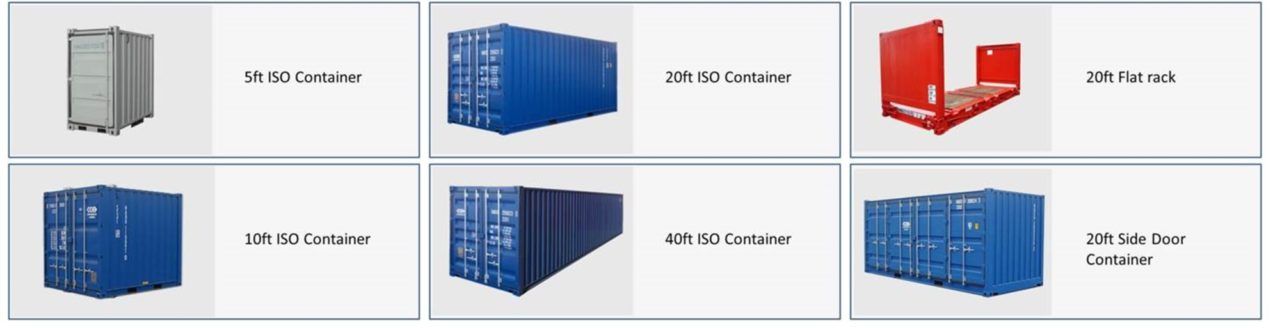

Intermodal Containers and Flatracks

The standard ISO containers’ numerous advantages of protection, reduction in handling and compatibility with ships, trains and vehicles are obtained when the container changes the mode of transport i.e. intermodal.

The International Standards Organisation (ISO) defines standards through an International Classification of Standards (ICS).

ICS 55 is for the packaging and distribution of goods and within that, 55.180.10 – General purpose containers include a range of standards for containers, with ISO 668 being the main one that defines dimensions and characteristics.

If the vehicle can fit within the most commonly used ISO containers it makes deployment to theatre that much easier, although perhaps not any quicker.

| Type | Door Width (m) | Door Height (m) | Interior Length (m) | Max Payload (tonnes) |

| 5ft Quadcon (1F) | 2.34 | 2.28 | 1.50 | 5.08 |

| 10ft Bicon (1D) | 2.34 | 2.28 | 2.80 | 10.16 |

| 20ft (1C) | 2.34 | 2.29 | 5.80 | 30.20 |

| 20ft Standard (1CC) | 2.34 | 2.28 | 5.80 | 28.80 |

| 20ft Pallet Wide | 2.40 | 2.28 | 5.80 | 28.25 |

| 40ft (1A) | 2.34 | 2.28 | 12.00 | 28.80 |

| 40ft Pallet Wide | 2.40 | 2.28 | 12.00 | 28.60 |

| 40ft Hi-Cube (1AAA) | 2.34 | 2.58 | 12.00 | 27.80 |

| 40ft Pallet Wide Hi-Cube | 2.40 | 2.58 | 12.0 | 27.80 |

Although the interior width and height are commonly quoted, the door aperture is more important for loading vehicles.

Hi-Cube containers are increasingly common, larger than the standard ISO container size, and designed to maximum volumetric efficiency.

Europallets are 1.2m x 0.8m and NATO standard pallets, often called industrial pallets in civilian use, are 1m x 1.2m. Neither of these two standard pallet sizes fit neatly into standard ISO containers and so the ‘pallet wide’ container is becoming increasingly popular.

Although for NATO/Industrial pallets in a 20ft container, there is no difference, for a 40-foot container length, having a pallet wide allows 24 instead of 21.

For Euro pallets, it is 30 instead of 25.

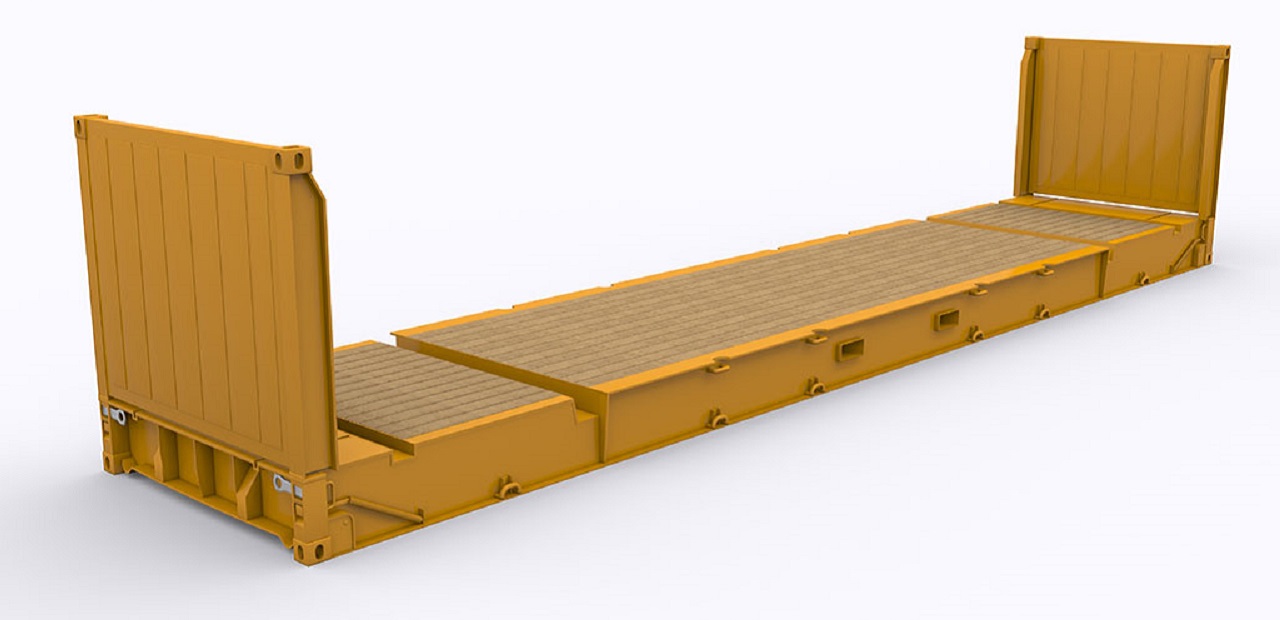

Intermodal flatracks are used for shipping heavy vehicles, equipment and materials, usually where they don’t fit inside a standard shipping container or where they require extra sturdiness.

They can be completely open or have integral ramps and corner posts and are designed to use the same handling equipment as more conventional containers.

Generally available in the same 20ft and 40ft ISO container footprint, although some outsize vehicles can be accommodated.

Flatracks are useful not only because they can be used on container ships and moved using container handling equipment, but because they allow vehicles to be quickly moved on and off RORO vessels without having to find drivers, start engines etc.

The RORO-handling vehicles and shuttle carriers can work quickly to move them.

Carrying capacities vary, but a good planning figure is 32 tonnes for a 20ft and 44 tonnes for a 40ft.

DROPS-style flatracks are also used for transporting vehicles.

As with intermodal flatracks, dimensions will be similar to an ISO container, although permissible payload is likely to be much lower.

The Vukka Frame from UNIT45 is another interesting alternative, using half-height open container frames, 20ft or 40ft.

Useful for lower-height vehicles.

Swap Bodies are more commonly used in Europe than in the UK (although they are increasingly being used in the UK by retailers and furniture manufacturers)

Swap bodies are not dissimilar to standard ISO containers but they are not designed for stacking and are generally much lighter, first invented in Germany in the early seventies.

| Internal Width (m) | Internal Height (m) | Internal Length (m) | Max Weight (tonnes) | |

| Class A | 2.55 | 2.69 | 12.2 to 13.6 | 34 |

| Class C | 2.47 | 2.69 | 7.67 | 14.5 |

Although of similar dimensions, swap body containers tend to have slightly more internal space and they are length optimised for European road legislation such as drawbar trailers.

Pallets – Conventional

Although one might not associate vehicles being carried on a pallet they can apply to smaller vehicles, e.g. quad bikes or e-bikes.

A MIL-STD 3028 JMIC has maximum internal dimensions of 1mx1.2m and a height of 840mm.

Military transport and logistics are built around the 1mx1.2m pallet, and potentially in the future, the JMIC. For small vehicles, it does make sense to explore options.

For example, a folding e-bike, now a common sight in many urban areas, and one that can be used to move NLAW about, could be folded down to fit JMIC for transport, two of them.

For quad-style ATVs, there are also a number of commercially available solutions for maximising battlegroup lift, stacking pallets for example.

Pallets – Air Transport

Vehicles would normally be driven on and off tactical transport aircraft so ordinarily aircraft pallets and load containers would not be a consideration

But for smaller and lighter vehicles, using aircraft pallets instead of driving on and off aircraft in the inter-theatre phase can lead both to space efficiency and open up opportunities for using non-tactical transport aircraft.

Tactical aircraft will be at a premium in any deployment, rapid or otherwise, so if we can provide options to avoid using them and use the thousands of civilian freight aircraft available, all good.

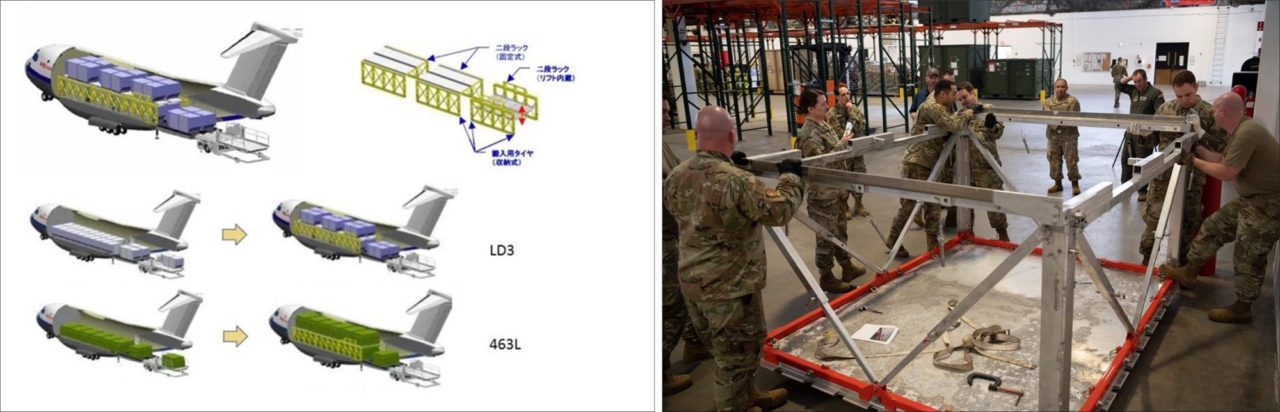

The 463L and ULD are two key systems used in the air carriage of goods.

The 463L pallet (also known as the HCU-6/E) is the main component of the 463L Materials Handling Support System.

The pallet and handling systems are designed with rolling in mind, a Euro/NATO pallet is lifted and shifted, and a 463L is rolled.

The useable space is 2.13m by 2.64m and two pallets can be linked together with couplers as shown below left.

Pallets would not be used for tactical landing but if the vehicle can fit within the 2.64m length of a 463L and under 4.5 tonnes they could be loaded across the width of the cargo bay rather than longitudinally.

An A400M can carry 7 such pallets (plus 2 on the ramp).

A C-17 is wide enough to carry 463L pallets two abreast, although they have to be rotated, and this would be without any seating. Without seating. 14, plus 4 on the ramp. With seating, 9, plus 2 on the ramp.

RAF A330 Voyager tanker aircraft can carry 463L pallets on the lower deck, 8 of them. Although we don’t have the version with the cargo floor on the upper deck, it can carry 26 463L pallets.

Because the height of both upper and lower cargo decks is affected by the fuselage curvature, this maximum number would be unlikely to be achievable for all but the lowest vehicles.

Interesting though.

There have also been a number of concepts for stacking 463L to maximum volumetric efficiency in large cargo aircraft.

Japan looked at a rolling frame (image left) and the USAF is working on a pallet frame (image right).

For small vehicles, this might also be useful.

463L pallets are mostly used on military cargo aircraft.

Although the image below is not an Airbus A330 (Voyager), it does provide a good illustration of what a typical wide-body airliner’s lower deck looks like.

Those aluminium containers on the lower deck, indicated by the red outline, are called LD3 Unit Load Devices, more often than not, stuffed with travellers’ suitcases.

The term Unit Load Device is a catch-all for a collection of pallets and containers used in the civilian air freight business.

There is a great deal more variety in dimensions and configurations than with the 463L system as they are often designed to be aircraft specific in order to absolutely maximise volume efficiency.

Specialist vehicle transport LD11 ULD’s are available from a number of manufacturers.

With the appropriate pallet, and assuming any vehicle is within dimensional and weight constraints, it could be potentially transported on a Voyager. VRR manufacture a ULD called the AMF/LD36 that is compatible with the Airbus A330 lower deck.

The internal base dimensions are 3.16m x 2.44m, with a maximum height of 1.6m, this should be one of the constraining dimension considerations, i.e. a small car.

Other non-463L flat pallets are also used.

For lighter and lower vehicles, racks (called VRA) are also availableto allow them to be stacked vertically for transport, maximising volume efficiency for larger civilian cargo aircraft.

Aircraft loaders will be required for civilian transport aircraft.

These generally have a maximum capacity of around 20 tonnes, the Atlas 4 at 19.6 tonnes and Atlas 5 at 22.7 tonnes are typical.

The civilian examples shown above might not be possible to replicate in a military context, different rules and regulations would apply, but it shows the potential for maximising scarce aircraft volume by staying within certain limiting dimensions and utilising systems already available in the commercial sector.

Air Despatch Platforms

Air despatch platforms, like the ATAX Platformfrom Irving, feature an airbag system for the heavier loads and integral shock absorption, and the flexible nature of the platform allows the platform to easily cope with ground undulation.

Each ATAX module supports a 4-tonne load and up to four modules can be combined for a maximum weight of 16 tonnes.Irvin GQ also make a trio of more conventional air despatch platforms

- Light: 23kg to 1,136kg

- Medium: 1,134kg to 8,100kg

- Heavy: 8,100kg to 16,000kg

As with helicopter sling loading, air despatch is a very complex and potentially very dangerous business, although in some cases, vital to operational success (see below from Mali)

Platform characteristics often change with aircraft type and payload figures tend to be given as ‘inclusive of rigging’.

Aircraft also have ramp limitations and minimum weights for various types of platforms.

Rail

Rail provides force commanders with the ability to move heavy equipment quickly, at both distance and scale. It is also generally cheaper than a road.

Moving the equipment by rail also allows drivers to travel by a separate means without the fatigue of driving long distances.

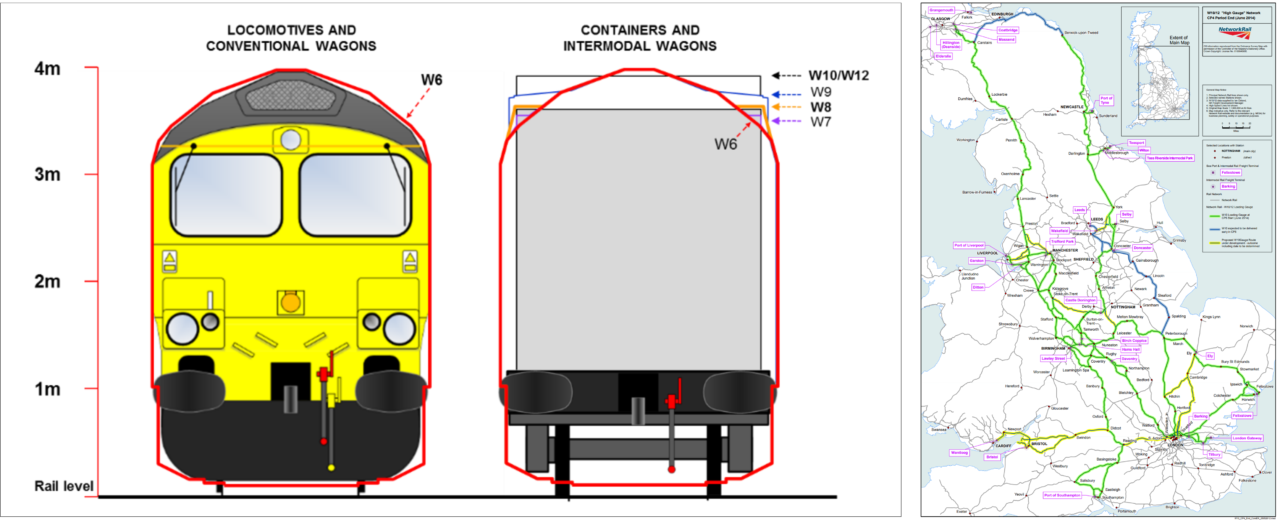

Rail transport is generally governed by a loading gauge.

And it is here that things get complicated.

Because the UK has the oldest rail network and was built at a time before containerisation, it has some of the smallest loading gauges in the world.

- W6a: Available over the majority of the British rail network.

- W8: Allows standard 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) high shipping containers to be carried on standard wagons.

- W9: Allows 2.9 m (9 ft 6 in) high Hi-Cube and pallet wide shipping containers to be carried on specialist wagons

- W10: Allows 2.9 m (9 ft 6 in) high Hi-Cube shipping containers to be carried on standard wagons

- W12: Slightly wider than W10 at 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) to accommodate refrigerated containers and is the recommended clearance for new structures, such as bridges and tunnels.

- UIC GC: Channel Tunnel and Channel Tunnel Rail Link to London

The size of the container or vehicle that can be conveyed depends both upon the size of the load that can be conveyed and the design of the rolling stock.

Modern low-slung wagon designs like the Davis SuperLow45 allow 45ft Hi-Cube containers (2.9m) to be carried on W9 routes.

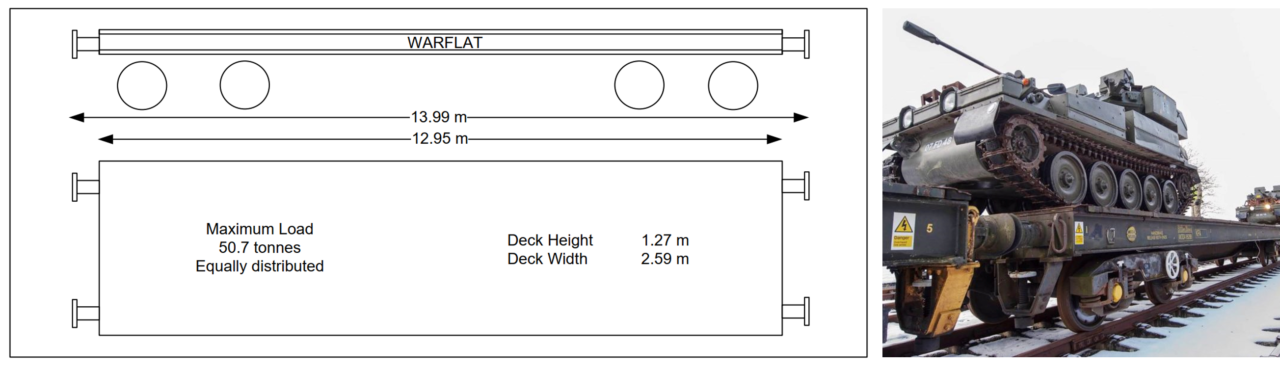

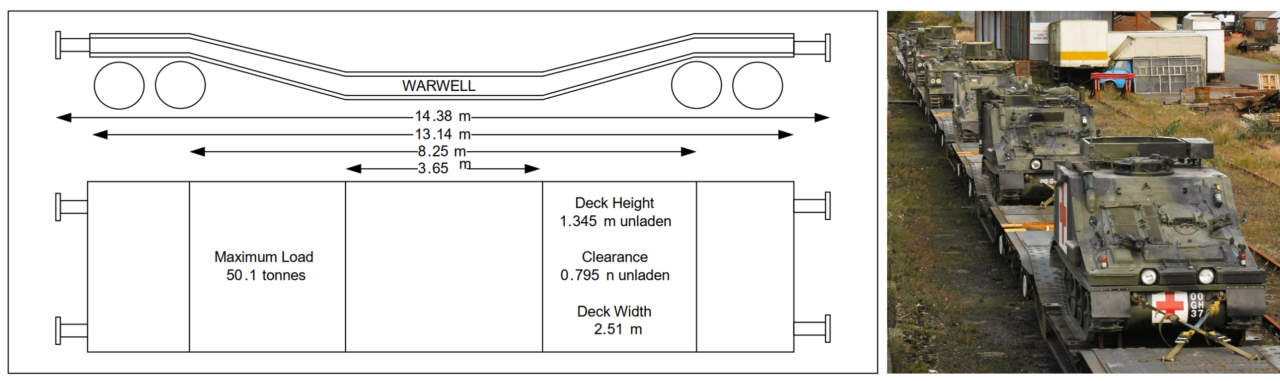

The old War Department rail wagon designs are still in service though, just.

Warflat

Warwell

Although newer designs are also increasingly used.

Although generally having larger loading gauges than the UK, there are differences across the continent, and there has been a general move to establishing rail freight corridors that can accommodate Hi-Cube and Swap Body type containers.

It is not easy to overhang a flatbed rail wagon because the load would hit platforms, and excess height is also a significant problem because of tunnels.

Challenger 2 and its derivatives are too wide for use on the UK rail network but CVR(T), Warrior and other vehicles can be moved by rail.

Challenger 2 can be moved on some European rail networks.

If we look at the constraining factors for vehicle design and railway mobility it is the width of a vehicle that is a key issue, to a lesser extent height and even less so, weight.

If a vehicle can be designed to be less than 2.35m wide and 2.39m high, the internal dimensions of a standard ISO container then it will be able to use the civilian rail container transport infrastructure in many countries.

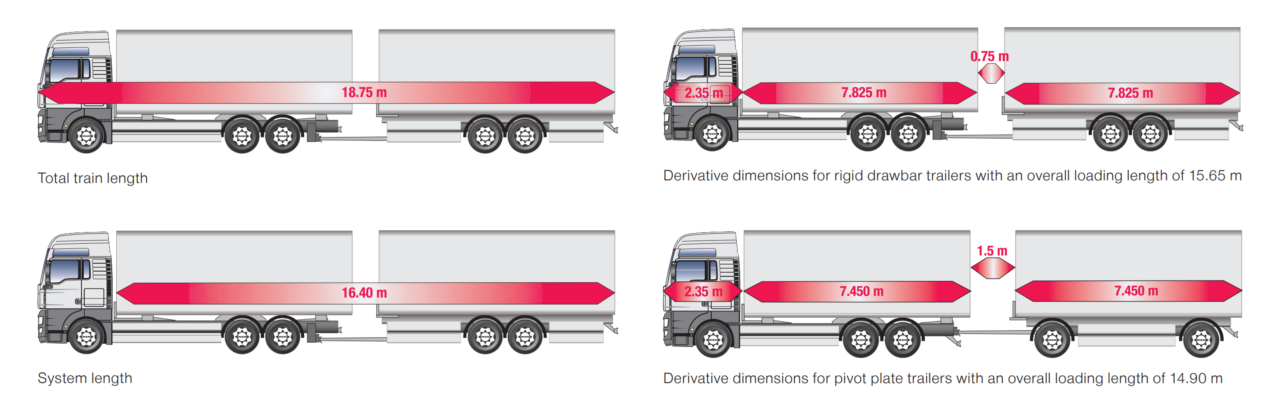

Road

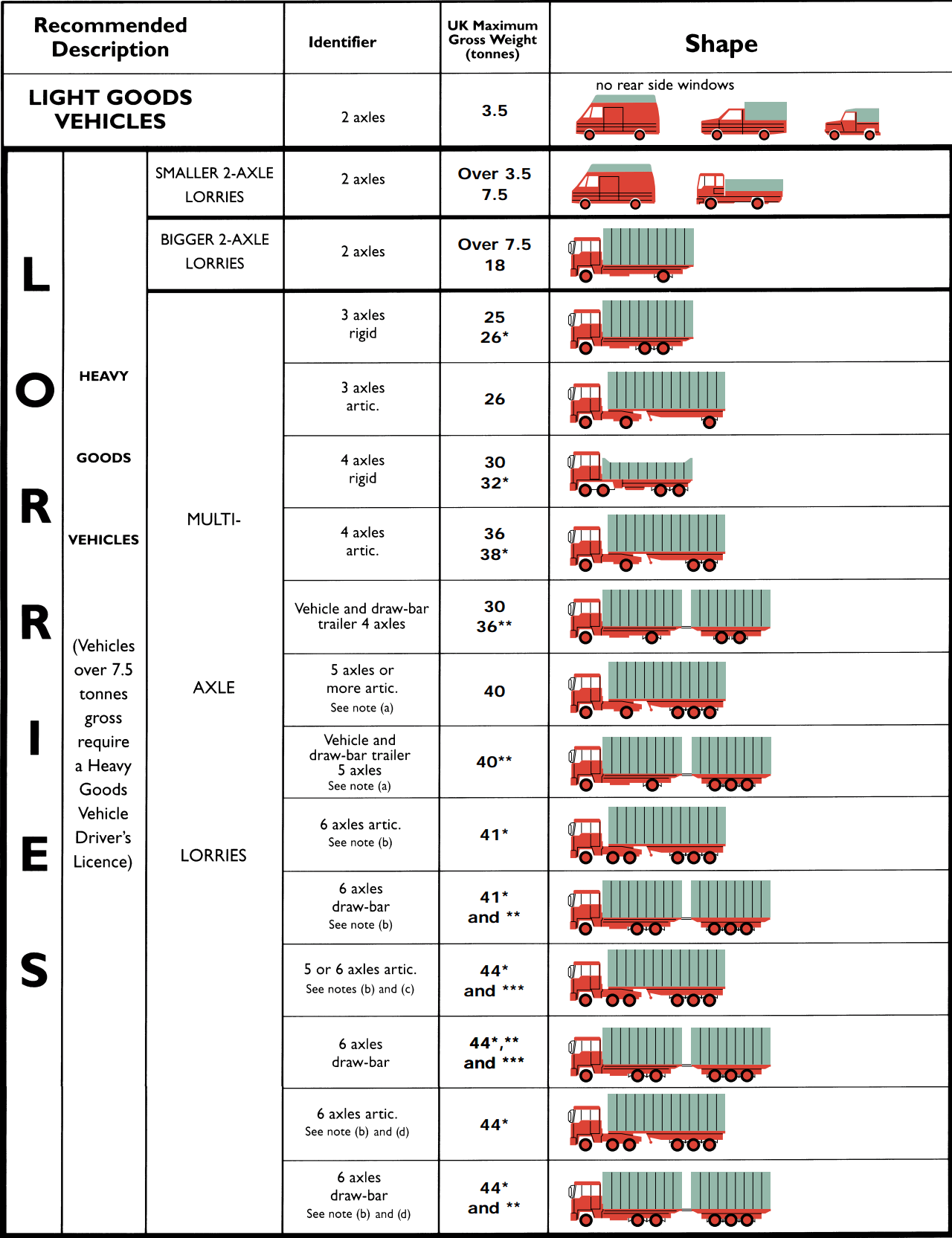

Road transportability is also important for training and UK movements and there are various weight limits as described in the diagram below.

Abnormal load regulations are complex but any vehicle with a weight over 44 tonnes, has an axle load of more than 10 tonnes, a width of more than 2.9m and has a rigid length of more than 18.65m is considered abnormal.

The minimum bridge height is mostly 5m unless otherwise marked, the same for overhead power cables, contrasting with some parts of Europe where the minimum is 4m.

Single-lane carriageways have a minimum width of 5.5m (allowing two cars to pass slowly) but this is often increased.

This is a good global average although obviously, some will be wider and some narrower.

Large trailers allow large vehicles, especially heavy vehicles, to be quickly transported to theatre.

The Oshkosh MTVR and HET tractor units were seen with three trailers

King GTS 110/7

With shorter vehicles, they can be carried two per trailer. The maximum payload is 89 tonnes and the loadbed is 13m long

Broshuis Light Equipment Tractor

This is a Broshuis Type 3ASD (LET) with a bogie load capacity of 30 tonnes and a flat load bed length of 6.5m.

As can be seen from the image below, the gooseneck area can also be used.

77 of these were designated as Interim Light Equipment Trailer (I-LET) but have since been upgraded to accommodate a max gross train weight of 68 tonnes, with 44 tonnes trailer payload.

Broshuis Improved Mobility Trailer

This is a Type 2APAS (IMT) with a bogie load capacity of 40 tonnes.

I think have now been disposed of as they were not UK road legal but included for information.

There are other trailers in use, a recovery trailer and small plant trailers for example.

The MAN/Rheinmetall trucks in British Army service can be used to transport smaller vehicles, as can the Iveco Trakkers used by the Royal Engineers for engineering plant.

| Vehicle | Loadbed Width (m) | Loadbed Length (m) | Max Payload (tonnes) |

| 2 axle HX | 2.4 | 3.8 | 6 |

| 3 Axle HX | 2.4 | 5.6 | 8 |

| 4 Axle HX | 2.4 | 6.1 | 14 |

| 3 Axle SX | 2.4 | 5.6 | 8 |

| Iveco Trakker | 2.4 | 4.9 | 16 |

Driving Licences

Although not perhaps directly related to transportability, it is still worth considering.

Vehicle weights and driving licences require management and training, it is important.

As an example, a Class B car licence qualifies a person to drive a vehicle with a Maximum Authorised Mass (MAM) of up to 3,500kg with up to eight passenger seats.

On a Class C1 licence, vehicles with a MAM between 3,500 and 7,500kg with a trailer up to 750kg.

With a C1E, the combined weight of a vehicle and trailer is 12,000kg.

Amphibious

The UK does not have any hovercraft that can transport vehicles but if there is an aspiration (doubtful) for the Griffon 8100TD which has a vehicle ramp and deck that is sized for a 12-tonne maximum weight and 20ft ISO container dimensions.

Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) Mk5 can carry an approximately 6-tonne payload with a ramp width of 2m.

The much larger Landing Craft Utility (LCU) Mk10 have a large payload and ramp width in excess of 3.5m and is able to carry heavy MBT class vehicles.

Although it seems future Commando will have less focus on landing heavy vehicles ashore.

The LPD’s (HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark) have various ramp limits.

Side ramp: 4.8m wide, 4.6m high and with a maximum vehicle weight of 18 tonnes

Vehicle Mezzanine Deck: 3.8m wide, 2.4m high and with a maximum vehicle weight of 13 tonnes

The stern ramp and vehicle deck can accommodate vehicles with a maximum weight of 72 tonnes.

Bridges

Although Military Load Classification (MLC) is not an indicator of total allowable weight, the carrying capacity of temporary bridges should factor into vehicle transportability.

| Bridge Type | Carriageway Width (m) | MLC |

| Logistic Support Bridge | 4.2 | 80-110 |

| Medium Girder Bridge Single Storey | 4.0 | 16-60 |

| Medium Girder Bridge Double Storey | 4.0 | 16-50 |

| Medium Girder Bridge Double Storey with Link Reinforcement | 4.0 | 60 |

| Dry Support Bridge | 4.3 | 80-110 |

It is difficult to predict average bridge conditions and strengths in developing nations.

Maximising Volumetric Efficiency

Logistics personnel will always seek to maximise volumetric efficiency.

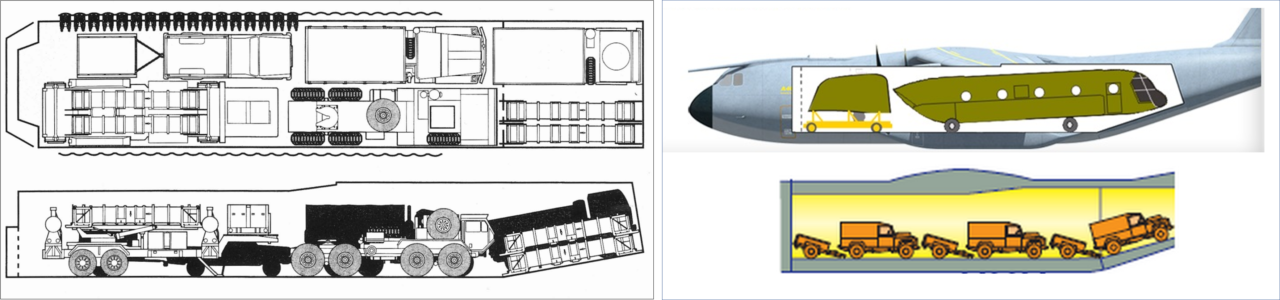

With a fixed dimension cargo hold, aircraft like the A400M or C-17 can maximise the carriage of vehicles and equipment using specific arrangements.

Load plans like those shown above (not to scale), the rear ramp area is used.

Stacking might also be used to max out the cube if those items that are being stacked allow it.

Stacking multiple vehicles to maximise the volume of a container would also be advantageous, although the image below is not a container specifically, one can imagine if it were a side opening Hi-Cube, how efficient it would be for transporting motorcycles by stacking them two high.

Vehicle stacking systems for container transport are now commonly used.

These allow vehicles to maximise the available space, in this example, 3 instead of 4.

Read more here

It is a rather ingenious solution, and British.

Fold-down cabs and roll cages, lowering suspension and removal of fixtures can also be used to reduce height.

In some cases, as shown in the image below, the particular design of the vehicle facilitates stacking.

The separate drive and payload module of Boxer also allow the vehicle to overcome specific ramp or floor limits.

Vehicles can also be transported with no fuel or payload to reduce weight.

Making Sense of it All

How can one make sense of the plethora of constraining factors described above?

It is important to state that dimensional and weight limits have a degree of fuzziness at the boundaries.

A fold-down roll bar might enable a vehicle to be carried inside a helicopter where a fixed cabin may not.

The height of a small vehicle might be enough to fit it laterally in a ULD if it is raised up on chocks.

A helicopter might be able to physically sling load a vehicle but cannot be used in practical terms because of the reduction in range or other flight performance metrics, especially as they are prone to performance degradation at high altitudes or temperatures.

We are often trying to fit square things into round holes, aircraft holds rarely have a uniform or square cross-section, railway tunnels are usually arched at the roof, and safety clearances will often depend on speed.

With that said, there are two methods of making some sort of sense, ordered lists of absolutes, and bundled them into logical categories.

Vehicles and/or prospective vehicles can then be compared to these lists and categories, and decisions made.

I cannot stress enough that these are estimated numbers, people make whole careers out of this stuff, it is a life’s work.

Taking the primary and secondary weights and dimensions into consideration, a shorthand of categories to describe many combinations and permutations can be defined.

They are not absolutes, as described above, there is always fuzziness at the margins

| Class | Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Max Weight (Tonnes) |

| A0 (25kg) | 1.1 | 0.60 | 0.8 | 0.025 |

| A (180kg) | 2.3 | 0.90 | 1.5 | 0.18 |

| B (500kg) | 2.4 | 1.30 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| C | 3.5 | 2.00 | 1.8 | 4 |

| D | 3.5 | 2.10 | 1.9 | 4 |

| E | 5.8 | 2.59 | 3.8 | 4 |

| F | 5.8 | 2.59 | 3.8 | 9 |

| G | 5.8 | 2.10 | 1.9 | 9 |

| H | 8.5 | 3.00 | 3.8 | 16 |

| I | 9.5 | 3.50 | 3.8 | 28-32 |

| J | 19.0 | 3.50 | 3.8 | 28-32 |

| K | 6.5 | 4.20 | 3.8 | 55 |

| L | 13.0 | 4.20 | 3.8 | 55 |

| M | 13.0 | 4.20 | 3.8 | 80 |

| N | 24.0 | 4.20 | 4.4 | 110 |

These various breakpoints are described further below.

| Category | Comment | Example |

| A0 (25kg) | Category A0 is probably the smallest practical means of wheeled transport and is more or less the size of a large rucksack. Most folded bicycles fit in this category.

They can be easily carried inside any of the in-service helicopters (except AH) and inside a JMIC or on a pallet, multiples could be carried, together with various ancilliaries. These could also be an air despatch door bundle. |  |

| A (180kg) | Category A is basically a motorcycle.

For carriage inside a Chinook or Merlin, if they could be arranged down the middle with handlebars crossing over, the seats might possibly be utilised although not sure if this would be allowed for safety reasons. Motorcycles could make use of specialised pallets to enable easier carriage on 463L footprint and loading inside containers, or when clipped together, as an underslung load carriage frame instead of using cargo nets. |  |

| B (500kg) | Category B is typically a quad bike style all-terrain vehicle (ATV) or some of the smaller UGV’s.

With a maximum weight of 500kg and a width of 1.2m, it would have to be an underslung load for Wildcat. Chinook and Merlin can carry them internally, multiples at a time. For helicopter portability in multiples, quad bikes are arguably not as efficient as a large vehicle and would require a lot of time to rig and de-rig if more than one or two were carried at a time For aircraft carriage, the volume would max out before payload so they would benefit from some type of multi-layer pallet, as shown above. Using a stacking would also benefit carriage on cargo vehicles. These larger quad bikes are an awkward fit inside ISO containers as their height prevents stacking, and two inside a Merlin and three inside a Chinook is not brilliant, 463L is only one per pallet. 3 axle quads and snowmobiles straddle category C and D |  |

| C (4 narrow low) | As above, but with a smaller height and width in order to be carried internally by Merlin (and V-22). Merlin has a narrow ramp.

This class of small ATV’s is defined by carriage inside a Merlin or Chinook, with the ability to carry two or more people at a time i.e. compact and 3-4 tonnes. A number of UGV’s are now based on this basic platform type and some pickup trucks might also fall within this category, as does the Supacat LRV, BV snow vehicles and LCVP Mark 5. |  |

| D (4 narrow) | As above, but sized for 2x Chinook internal carriage. This class of vehicles aligns very well with the US Army Blackhawk/Chinook combination as they do not have a 4-tonne lift helicopter with a cargo ramp-like Merlin

The weight allows two to be carried as an underslung load by Chinook or one by Merlin/Blackhawk/AW-149. Can also be carried inside any container or swap body, in multiples, depending on length and height (including stacking arrangements) |  |

| E (4) | This category dispenses with internal carriage but stays at 4 tonnes.

This means one on a sling for Merlin/AW149 and two for a Chinook. Multiples can be carried on A400M, C-17 and AN-124. Keeping below 3.5 tonnes will have licence benefits. For the most part, this covers very light engineering plant and not much else, although the small commercial/van-derived products or even MRV-1 would also be included. |  |

| F (9 Short Wide) | Can be carried as a load on the three and 4 axle MAN SV’s, Iveco Trakkers, carried on a 20ft ISO flatrack or hooklift flatrack, Light Equipment Trailer, and swap bodies,

Carried as an underslung load by Chinook and near max as by CH-53K Air despatch capable LPD side ramp accessible and would not be an abnormal load. Keep under 7.5 tonnes and there might be some driving licence benefit. Moving outside of the 2.34m ISO container limit to 2.59m still allows deployment by swap body and Warflat, keeps it under abnormal load limits but means it cannot be carried internally in a Chinook. Two abreast would be possible in C-17 although only one abreast in an A400M. With a maximum length of 5.8m, 4 can be carried in a C17 and three in an A400M. An AN-124 would be able to carry ten. Typical vehicles include CVR(T), Foxhound, Panther, and a JCB 4CX. |  |

| G (9 Short Narrow Low) | Same weight category as above, but narrower in the hips, at 2.1m, and lower.

This brings internal Chinook carriage into play, certainly a niche. It also means we can make extensive use of standard ISO containers and swap bodies. The width of 2.1m means that two abreast is still impossible in an A400M so the A400M/C-17/AN-124 numbers are the same as above. Jackal falls into this category, as does Land Rover and Pinzgauer This category maximises transportability, enjoying all the benefits of the above, but narrow enough to fit inside an ISO container and Chinook. |  |

| H (16 Short) | The heaviest class at which air despatch is possible.

This weight also allows two to be carried in an A400M. 16 tonnes is approximately the unladen weight of a Patria 6×6 or Fuchs 6×6. Transporting a vehicle without fuel, ammunition or people might not be ideal but it does allow aircraft payload to be maximised. Bulldog also falls comfortably in this category, as does Stormer, Viking, and many items of engineering plant, At under 8.5m length, the two per A400M can be retained. For carrying two abreast, the 3m width goes against the C-17 carriage, so it would still only be two per C-17. AN-124 could carry six. LPD side ramp would also be accessible, as would CH-53K underslung capacity, at a pinch. This weight can also be recovered by a MAN SV Recovery variant and if were constrained slightly in length, a possible 20ft Flatrack load This category would also be carried by a C-130J. |  |

| I (32 Short) | Somewhere near the max payload for an A400M, two per C-17 or three per An-124.

At under 9.5m long, two could be carried inside a C-17. Boxer is in this category although as we have seen, the drive and payload modules need to be split for the A400M carriage. Other vehicles include Terrier, Wolfhound, and MLRS. This size is also compatible with an ISO Flatrack. Only one would be carried on a HET trailer |  |

| J (32 Long) | Same weight range as above but longer, at 16m.

This extra length accommodates trucks and longer vehicles such as the articulated fuel and water tankers, AC35 crane, Volvo graders, a loaded 4 axle MAN SV, loaded Iveco SLDT and MAN Recovery vehicle for example. If being carried on a low loader, they would all be an abnormal load. Only one would be possible in an A400M or C-17 |  |

| K (55 Short) | Not quite MBT class at around 40-55 tonnes, one would be able to be carried in a C-17, and two in AN-124.

A400M carriage would not be possible. Ajax (and variants) would fit into this category and any possible future Warrior replacement. If they were under 40 tonnes, two could also be carried on a HET, although this would be an uncommon move. |  |

| L (55 Long) | In the same weight class as above, but larger. Mostly characterised by extremely large engineering plant like the Terex AC55 crane or Kalmar Rough Terrain Container Handler. Can be carried on a HET and King GTS trailer. Able to be carried on a C-17 or AN-124

Because Boxer is just under 8m it is included in this category. This would mean only one Boxer can be carried on a HET trailer, regardless of weight. As described above, the drive and payload module can be detached to enable carriage by A400M. The taller variants, air defence and 155mm would also fall into this category, as long as their height did not exceed 3.8m. Some of these might be able to self-deploy, e.g. a Terex crane or Boxer can drive considerable distances without being carried on a trailer. |  |

| M (80) | Main Battle Tank and derivatives. Weights are gradually increasing across NATO armies, appliqué armour, APS and other systems mean that the norm is likely to be MLC80, not MLC70 as is the planning metric used now.

This puts these newer and heavier MBT’s beyond C-17 and into AN-124 territory, or just road and rail. Some variants are wider than the base vehicle, Titan, for example, is 4.2m wide when carrying a Close Support Bridge. In transport, bridges would not be carried but with appliqué armour, a CR3 is likely to be 4.2m in any case. The maximum length is 13m to fit on a King GTS HET trailer The maximum height is 3.8m to accommodate 1m for a trailer or railway wagon, thus fitting underneath the most common unmarked bridge |  |

| N (110 Long) | The largest and heaviest vehicle, a heavy equipment transporter and a loaded trailer. (technically, the heaviest and largest is one of these being recovered/towed but as a single load, this is the biggest). It is always going to be an abnormal load for road and rail transport. |  |

Summary

As can be seen from above, there are a number of natural break points that assist with transportability, especially when considering ‘multiples’ of vehicles.

But the world of requirements setting does not revolve entirely upon fitting vehicles neatly into available transport, nor should it.

But despite the complexity (and the above only hint at a scratch on the surface), transportability should at least be a serious consideration.

See you in the comments.

Change Status

| Change Date | Change Record |

| 12/06/2022 | initial issue |

I suppose you forgot one aspect of the topic:

https://defense-and-freedom.blogspot.com/2012/12/parasitic-land-vehicles-for-army.html