Do military motorcycles and e-bikes have a future in the British Army, a few thoughts on the subject.

A Short History of Military Motorcycles

The military connection to early motorcycles is quite interesting with a collection of recognisable names such as Royal Enfield and Birmingham Small Arms (BSA).

As designs matured from powered bicycles to more recognisable and mass-produced motorcycles in the late eighteen hundreds and early nineteen hundred, Pancho Villa was the first recognised user of motorcycles in a military context during the early Mexican Revolution period from 1911 onwards.

Pancho Villa realised that Indian motorcycles offered an ideal means of fast hit-and-run raids.

The US General, John Pershing also used motorcycles to deal with Pancho a few years later, without much success as it happened.

As this was happening, WWI also provided numerous examples of armies using motorcycles.

Indian, Harley-Davidson, and Triumph, all joined the war effort.

The Triumph Model H was widely considered the first modern motorcycle, and approximately thirty thousand were supplied.

Different nations had slightly different doctrinal approaches to using motorcycles with the British and Germans using them primarily (although not exclusively) for communication (despatch riders) and the US had a more expansive view of how they could be used, perhaps informed by their Mexico experiences.

As WWII came, designs, of course, matured, the famous shaft-driven BMW R75 (with an engine reverse-engineered from the Douglas Boxer), Soviet Dneper M-72 (a derivative of captured R-71s), the indestructible Harley Davidson WLA, and the lightweight 2-stroke Royal Enfield WD/RE, or ‘Flying Flea’, to name but a few examples.

These were used with and without sidecars, as weapons or casualty carriers, for despatch riders, military police and paratroopers.

Bicycles were also used extensively by all parties.

Post-war, and as communications equipment became more reliant and four-wheel drive vehicles more reliable, the military use of motorcycles was scaled back to mostly niche roles; special forces, base security, the odd reconnaissance application, and of course, the Vespa 150 TAP, or Bazooka Scooter.

The sidecar, trailer, and role-specific modifications had given way to militarised civilian designs, such as the Armstrong/Harley-Davidson MT350.

Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq provided an opportunity for more use, but they were mostly limited in application.

Lithuanian special forces used motorcycles in Afghanistan, according to Stars and Stripes magazine;

The effectiveness of being lighter and faster wasn’t lost on Lithuanian Special Forces in Afghanistan’s rugged Zabul Province who, in 2007, parked their armored trucks and cowboyed-up on high-powered Yamaha and KTM motocross bikes to take the fight to the enemy. In a place where the roads are littered with improvised bombs the move seemed risky, but five years later the Lithuanians were still in the saddle. “These motorcycles were our lucky card,” said Maj. Liutauras, the Lithuanian commander in Zabul last summer, who, like many special operators, prefers to be identified only by his first name. The Lithuanians’ first patrols in armored vehicles, were repeatedly ambushed by insurgents on motorcycles, he said.

“They were able to reorganize and hit us hard again and again,” he said.

So the Special Forces adapted. They acquired motocross bikes and set up a training area in Lithuania to learn how to maneuver in rough terrain, jump and chase down skilled enemy riders.cThe Lithuanians’ speed on the motorcycles quickly allowed them to chase down enemy observers and prevent ambushes. And the motorcycles were too light to trigger many of the Taliban’s booby traps, often set with heavy springs that allow civilian traffic to pass unharmed but detonate when a heavy armored vehicle passes.

“We are risking a lot but this risk is measured,” Liutauras said, adding that his men often patrolled with just six bikes. “Our aggressiveness and our tempo and advance to contact is always a win.” Motorcycles are also popular with Afghan security forces, who even use them to drag rakes in search of roadside bombs — a technique not recommended by international troops. “Everyone rides motorcycles in Afghanistan,” Liutauras said. “The main thing is making them understand taking care of them.”

Liutauras said the motorcycles have protected Lithuanian forces in Afghanistan by enabling them to catch more Taliban bomb makers, meaning fewer bombs in their area of operations. The insurgents’ machines were clearly inferior to the Lithuanians’ 450cc to 550cc Japanese and Austrian bikes. However, the Taliban are very experienced riders, Liutauras said. “They have been living here for hundreds of years so they know all the routes and they can do 80 kmph (50 mph),” he said. “We can do 100 kmph (62 mph) or more but for us it is sometimes hard to catch them because they are light and we have body armor and weapons.”

The only casualties suffered by the Lithuanian motorcycle troops were broken arms and ribs from soldiers who have fallen off their bikes, Liutauras said. The Lithuanians also have passed on successful motorcycle tactics to Afghan troops, he said. “We want to train them to drive off road and give them the best expertise,” Liutauras said. “When ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) forces go, their fast moving motorcycles will be one of the most effective measures.

Years later, in Syria, cities turned out to be excellent environments for motorcycle operations.

This article from Sputnik News describes the value of motorcycles in the close urban terrain of Salma in Syria.

The way we fight has changed since the beginning of the war, and we have developed our offensive methods,” said Hany, a 25-year soldier with the Syrian Army. “Nowadays, we use motorbikes for their speed and mobility. My bike is harder to track and is too light to set off landmines.” “It was the use of more than 80 motorbikes in the last battle for the town that had the greatest impact in terms of winning in the final 72 hours,”

Continuing…

one field commander said. “The motorbikes allowed us to transfer the wounded, carry light ammunition and food and were used by fighters carrying machine guns and night vision binoculars. “We’ve come up with an advanced course on street fighting and guerilla warfare, and fighting on motorbikes may become a tactic that regular armies come to rely on. Eventually, they’ll become an essential piece of equipment, like a gun or ammunition”

Sidecars made a brief return, and so did their use as weapon carriers, although again, in limited numbers.

The Nordic and Baltic countries’ armed forces still use military motorcycles, and French special forces made extensive use in Mali.

More recently, Ukraine has made excellent use of a range of motorcycles and e-bikes for anti-tank ambushes, general reconnaissance and other similar roles.

Over a century later, Ukrainian forces came to the same conclusion as Pancho Villa, instead of riding a 1914 Indian and carrying a six-shooter, they went for Delfast Top e-bikes and NLAW rockets.

E-bikes are so hot right now, that everyone is using or hoping to use them, even the British Army, trialling the Stealth H-52 e-bike from Australia.

The history of military motorcycles appears to be cyclical, the technology changes, but conflict drives users to trade peacetime training and safety issues for wartime expedience.

Motorcycle and E-Bike Types

Motorcycles and e-bikes have experienced over a century of development, moving a long way from their heritage of simple-powered bicycles.

Internal Combustion — Compact Motorcycles

Let’s start with a niche!

Whilst folding bicycles (manual or electric) are relatively common, folding or compact motorcycles are much less so.

Although the famous Honda Motocompo and Monkey Bikes are no longer in production, and the Excelsior Wellbike, is long gone, the modern-day successor is the Italian-made DiBlasio R7E folding scooter.

With a 50cc engine, it has a range of approximately 120 km, a top speed of 45kph, and a weight of just under 32 kg.

Honda China has resurrected the Motocompo concept and now markets an electric version called the e-Dax Minimoto.

Non-folding, but still compact, designs are produced in the USA by Coleman Powersports, with seven models in their mini bike range.

Larger than the DiBlasi models, they are also heavier, with larger engines and improved performance.

Internal Combustion — Two-Wheel Drive Motorcycles

The low weight and high power-to-weight ratio of conventional motorcycles deliver a lot of mobility, but where terrain accessibility is a key performance criterion, a few manufacturers make motorcycles where both wheels are driven.

Although several sports manufacturers now produce all-wheel driven motorcycles, the two with a more military range are Christini and Rokon, each with different design approaches and uses.

The single-cylinder four-stroke Christini AWD Military has been refined over several years, including foam-filled tyres, GPS, anti-stall automatic clutch and additional protection for vulnerable areas.

The Rokon Ranger and Trail-Breaker use a chain-driven front wheel and have been continually developed over twenty-five years, with a wealth of accessories available. The tyres can be filled with water or fuel, both wheels are powered and with the 200cc petrol engine, can tow 900 kg loads.

There is also a longer wheelbase version available with an extended load bed called the Mototractor and various sidecars and trailers can be used.

The King Abdullah II Design and Development Bureau in Jordan has developed a specialist military version of the AB32 Rokon Desert Ranger, and it is in service with Jordanian forces.

KTM and Kawasaki have also developed all-wheel-drive motorcycles with different approaches, and hydraulic and mechanical connections to the front wheel.

All-wheel drive cannot substitute for skill, but it does help a skilled rider, although the extra weight might not be welcome.

Internal Combustion — Motocross and Enduro

The British Army’s Harley Davidson-built Armstrong MT350 Motorcycles are now long obsolete, although some Kawasaki KLR and Honda XR/WR 250/400 were purchased from CJ Ball for specialist users, they were not used widely.

The Hayes Diversified Technologies M1030M1 was a modified Kawasaki KLR650 using technology developed at the Royal Military College of Science (Cranfield), its key feature was the ability to use military/civilian diesel, Bio-Diesel (B20 or B100), JP4, JP5, JP8, AVTR and even Kerosene.

These are no longer available.

Apart from some minor modifications, weapons panniers and lighting, for example, a military enduro bike is not that much different from a civilian enduro bike, they are widely available.

Take your pick from Kawasaki or KTM, to name two.

Electric — Folding Scooter or Bicycle

Taking their existing fossil fuel design as a starting point, DiBlasi has an electric version, the R-70 Electric.

The maximum speed is 40kph, with an average range of 50 km.

Folding bicycles specifically for parachuting go back many years, but in 1997, DARPA issued a contract to Montague in the US to develop the Tactical Electric No Signature (TENS) Mountain Bike.

This was developed further, and similar models are available from Montague.

Although without the military heritage of the Paratrooper, folding e-bikes are popular with commuters and outdoor enthusiasts, where their compactness is the main feature.

From cheap Chinese imports to the premium folding Brompton, there is enormous choice.

The British Army uses Makita 18v and 40v battery power tools.

Makita also makes a 18v folding e-bike and likely a 40v version.

The Mosphera Military E Vehicle is a robust and rugged electric scooter with a range of 150 km.

Electric — Mountain Bikes

Moving up the power band from commuter and leisure electric bicycles, ‘no pedal assist’ models are, again, widely available from vendors that have specific militarised models such as Trefecta, Sur Ron, Delfast, Eleek, Stealth, and Stalker Mad Bikes.

Higher-performance models have payloads of approximately 150 kg.

The Stalker Mad Bike Carnivore in the image below, under test by the French armed forces, is typical.

Or the Sur Ron Light Bee, being tested by 16 Air Assault Brigade.

The Light Bee weighs less than 50 kg with a range of 100 km plus.

Technically, not an electric mountain bike, the Zero MMX is in service with US forces

It has a high top speed of 137kph, but a shorter endurance of two hours.

Electric — Cargo Bikes

Generally used for urban logistics, cargo e-bikes sacrifice speed for carrying capacity, and in some cases, towing capacity.

At their simplest, they are just sturdier conventional designs fitted with racks and panniers. Longer wheelbase (or long tail) designs have longer rear load beds for low-density cargo.

The load beds can be optimised for standard Euro containers or bespoke loads.

Large logistics companies are investing in electric last-mile logistics with smart intermodal containers and pallets.

Trailers are now frequently used, also for low-density loads.

Use Cases

A bit of history, and a broad overview of the types available, but how can they used?

Self-Deployment and Operational Movement

For a force with access to more conventional transport, motorcycles are not an efficient means of self-deployment.

One particular exception to this rule that might be worth further examination.

As discussed in several previous posts, the increasing proliferation of advanced air defence systems means that parachuting will be at increasing stand-off distances.

And if you only have a pair of size tens, that creates a lot of distance to cover.

Assuming a 5kph marching speed, the parachute landed force on foot could cover 20 km in four hours and hold a potential area of 1,250 km2 under threat.

Now assume a speed of 40kph with a motorcycle, the distance rises to 160 km and the area, 80,000 km2

20 km is inside the engagement zone of all but the shortest-range systems, 160 km is not.

Ideally, 16 Air Assault Brigade would have access to a vehicle air despatch platform that was integrated with the A400M, but it doesn’t, instead, it has either a single or double Container Delivery System (CDS) pallet.

Motorcycles are small and light enough to use the CDS method of air despatch (as are quad ATVs) so remain a viable means of covering the increasing stand-off distances described above.

However, they are not particularly volumetrically efficient and would displace other high-value loads.

Like commuters, paratroopers should value compactness.

This is the niche occupied by folding designs

Getting onto a train with a folding Brompton or packing them into a CDS bag for air despatch from an A400M, is the same.

With a non-folding design, a single A400M could despatch 24 e-bikes or motorcycles, just not good enough. Swap to a DiBlasi R7 and a single CDS pallet can comfortably carry four, or 96 per A400M.

Use a folding electric Brompton or Makita, now a single A400M can air despatch 192 of them.

All would need a refuel or battery change to complete the 160 km objective, but it would be easy to envisage a mixed load of folding motorcycles or e-bikes with a handful of quad ATVs and trailers that would be used for personal equipment, stores, and additional fuel or batteries.

Beyond the comedy factor of riding on a folding scooter that looks like something from Dumb and Dumber.

Accepting terrain limitations of these small devices results in a viable means of deployment over an operationally significant distance and allows them to arrive ready for aggro.

Tactical Roles

Examining tactical roles requires analysis of the unique characteristics of two-wheeled vehicles and then a secondary analysis that compares internal combustion to electric.

Compared to a quad bike ATV or larger vehicle, narrow paths, steep inclines, and a lot of urban terrain lend themselves well to the narrow footprint of a two-wheel vehicle.

Bicycles and motorbikes can be laid on the ground sideways and are therefore much easier to conceal and protect than a quad bike.

Small size, high speed, terrain accessibility and low signatures are their key advantages.

Cavalry, scouting, and reconnaissance roles all used horses, and there is no reason that in some cases, they could not exploit two-wheeled vehicles for the same.

Quickly checking if a road or bridge is accessible for a follow-on force, moving a sniper team into position, setting up observation points, checking arcs, and infiltration to create an anti-tank ambush are all good examples where the small size of two-wheeled vehicles in complex terrain begins to make sense.

In an age of complex and denied radio environments, despatch riding may yet make a comeback, and in addition to messages, collected video and imagery might be part of that message.

If safe, rapidly moving a medic with basic supplies to a casualty might provide options for casualty stabilisation.

Those roles are familiar, and each has historical precedent, they might be covered by quad ATVs or on foot today, so the additional speed and mobility afforded by two wheels can only be advantageous.

Without falling into the trap of stating the obvious, no motorcycle can outrun a bullet, and speed versus protection is an important factor to consider.

They are not a replacement for a better-protected vehicle but an extension of that vehicle or an improvement on Shanks’ pony.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Pros and Cons

As always, there are pros and cons, in this case, they rest on four issues.

The Problem of Payload

Most two-wheeled vehicles have limited payload beyond the rider.

Panniers and racks can help with distribution, but the limitation remains.

Modern soldiers carry significant weight and what works for dismounted movement will not work when riding, a heavy Bergen or weapon carried on the rider’s back will significantly degrade control and safety.

This video from the Australian Army provides a good example of this.

Not even a personal weapon.

Cargo bikes address this by moving loads off the rider and placing them lower down or in properly designed carriers or trailers.

Cargo bikes are for firm road surfaces, ideal in an urban environment, but less so in a forest.

These limitations mean that without the support of a larger vehicle or from a static location, usefulness is limited.

Sidecars; you might as well use a quad bike or side-by-side ATV.

Trailers may well be applicable.

Single wheel

Twin wheel

Some designs even have power assist like those from Carla Cargo

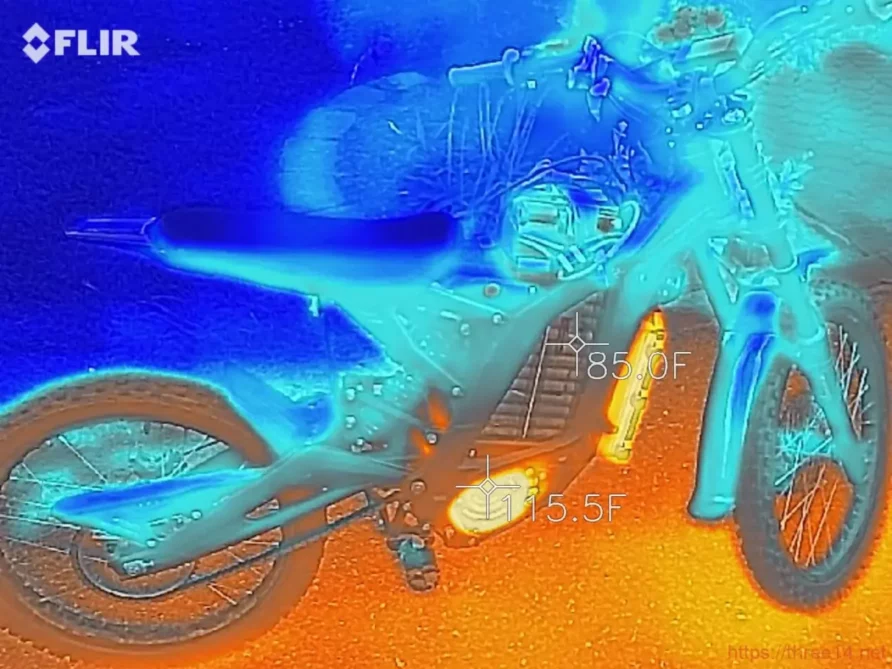

The Problem of Signature

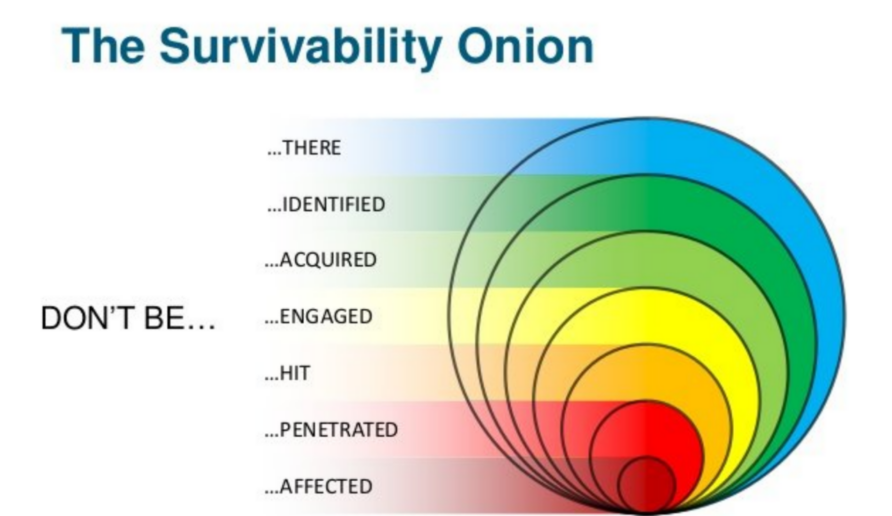

In the survivability onion, not being seen is a high priority.

Despite their small visual signature, Internal combustion engines have significant heat signatures that are difficult to mask on a motorcycle.

Even with modern exhausts, noise can exceed 80dB/A at 100m, equivalent to a ringing telephone or alarm clock.

In comparison, the noise and heat signatures of electric motorcycles and e-bikes are significantly lower.

The thermal signature of an e-bike is not nothing, and the rider is of course another issue with detection, but it is much lower than with internal combustion.

Although relatively distinct, and somewhat depending on the drive mechanism, a typical e-bike emits approximately 60 dB/A when moving, the sound of a normal conversation.

At the same 100m as above, inaudible.

This is the single most important feature of electric bikes in tactical settings, it is what unlocks their potential.

The Problem of Endurance

Despite the significant improvement in electrical and battery technology, driven in no small part by the portable communications and power tool markets, batteries still have some way to overcome their energy density and recharge disadvantages.

In much of the publicity around the 16 Air Assault Brigade trialling the Sur Ron Light Bee, there was a comparison to the Royal Enfield WD/RE ‘Flying Flea’ from WWII.

Both weigh approximately 50 kg, the 2023 design can travel 100 km before needing a ‘refuel’, yet the relic from WWII could easily do 240 km.

Battery swapping or filling a small fuel tank will be of a similar duration, but a 7-litre fuel tank for the WD/RE weighs 5 kg and the Sur Ron 38Ah battery, 10 kg.

It needs fuel to recharge (unless we are using solar), and over three hours to do it.

Power scavenging will help, regenerative breaking and more efficient drivetrains also, but there can be no doubt the range and endurance of e-bikes are a limiting factor.

This might be of less significance when tactics and systems are developed, but we should not casually dismiss them.

The Problem of Skill

The simple fact is, with a smaller army, we cannot afford to be cavalier about training injuries and the world of safety legislation and its application has moved on.

Final Thoughts

There will always be niche roles for motorcycles (and e-bikes), special forces, and examples like this from @jeffreyvail

E-bikes, especially, have significant potential, but wider adoption of both motorcycles and e-bikes needs to address some or all of these challenges.

Power

The power issue may be addressed by simply accepting the limitations of current technology and adapting tactics and procedures to meet them.

Is tethering to a ‘mothership’ that can provide spare batteries and charging facilities that big a deal?

Technology will improve, and power density will only get better.

It would be preferable to avoid yet another proprietary battery technology and insist on NATO standard radio batteries, or use Makita 18v LXT or 40v XGT batteries.

Vehicle Integration

If tethering to a vehicle makes sense, racks, and integral charging facilities will be integrated.

If we can use wireless charging pads for power tools and mobile phones, why not e-bikes?

More complex vehicles will require more complex integration.

With Boxer used to carry dismounted reconnaissance cavalry troopers, it should be fitted for internal or external carriage of four or five e-bikes, with spare wheels, batteries and a charging facility.

Logistics and Support

Please, in all the excitement, let’s not forget the pallets.

And by pallets, I mean logistics and support.

Horses for Courses

There is no single motorcycle or e-bike design that beats all others.

Something suitable for infiltration and an anti-tank ambush in a forest might not be for small unit resupply in an urban environment, and no matter how cool they look, a folding moped is not an act of war!

As the industry develops alternatives, and governments bring them into better-defined regulatory and legal frameworks, these will also influence types and configurations.

Whether an e-bike has pedals will also be a key part of determining utility and training, as this is a factor in future licencing.

Further Reading

See you in the comments…

And no Marc, no I am not!

Read more (Affiliate Link)

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Teh, does everyone in the coy know how to ride? My recce coy had a lot of casualties from motorcycle training, up to 50% at one time, especially when they put people who did not even know how to ride a bicycle through the course. Usually broken something. Nose, arm, leg etc.

Though to be fair, some of it was from extreme conditions like NVG riding.

To even gain entry into motorbike training you need to have civilian motorbike license and without license no training no military motorbike license.

That Facebook entry for Finland seemed to be advertising for volunteers into the “Dirt Bike Corps”… and the first two had already done “their time” but google translate seemed to think they want to at the top of the queue – again!

The picture and text are totally unrelated. The text is about upcoming draft.

Teh, at least that’s a smarter system than putting people into traction. I don’ know why we don’t do it that way other than maybe too small a motorcycle riding base, people prefer to use cars or public transport.

Oh, boy. I really wrote about almost everything military already, did I?

No, this time I will resist dropping my link.- :-)

All electric motorcycles – this is going to be interested in very cold weather, when internal combustion engines have start issues. Would an EV start immediately or would the battery say “no” during starting procedure or after a short distance? So far I found no EV specs for really, really cold weather (below -20°C).

There’s a consensus that AWD makes motorcycle handling easier off-road and is thus a plus, though there’s usually very little power on the front wheel (less than 20% IIRC).

The golden middle for enduros (payload, agility) appears to be at 400…450 ccm petrol engines. The much smaller bikes don’t have the payload and endurance and the bigger ones are difficult to handle for non-bodybuilders in an offroad setting. Very, very tiring. Sadly, the Hayes diesel bikes are heavy, and even heavier than petrol bikes of similar cylinder volumes.

Petrol bikes are a no go IMO (sad!). Most armies simply have no petrol in the supply system in the field. They only know diesel (and partially kerosene) in the field.

Petrol works still fine in peacetime training, but what about mobile ops for weeks during an actual campaign? Would they be able to supply themselves from gas stations (that might have no electrical power supply) and from siphoning off civilian cars left that were behind?

(I have a motorcycle license, but am no experienced motorcyclist and never attended an offroad bike course.)

@SO, I don’t think you’ll have a problem at the start, RE

“specs for really, really cold weather (below -20°C)”

– you’ll just run out of charge 30% faster than in ideal conditions (for the battery, that is)

The bikes I used in the army run on petrol….

The Australian SASR use dirt bikes in their desert patrols also

No comments on the content. I do notice that there is an omission though as you don’t consider how motorcycles arrive ready for use where and when needed. The UK MoD is very good at adding kit to a unit staff table with no regard for the space required to move it all. The consequence for motorcycles is arrival in place damaged and unserviceable due to manhandling and poor stowage. When deploying forward, a trailer for several motorcycles and their supplies or at least a rack to hang them on a vehicle is more than a luxury. I doubt that even dedicated motorbike Yee-Haws see the funny side of riding rough for 600km just because.

https://www.defencetalk.com/military/photos/sasr-perentie-6×6-stock-shot.2403/

Great review for the https://surron-ebikes.com/

Great information. i love the content. https://surronultrabee.com/