The Individual Protection Kit (IPK), or KIP, was a Military Experimental Engineering Establishment (MEXE) design from the fifties.

Its purpose was to provide infantry with an easily carried method of providing some measure of Overhead Protection (OHP) without mechanical assistance, at stage 1.

Supplied in a sealed nylon packet, the IPK consisted of a grand total of four components, 6 aluminium pegs, a length of white nylon cordage, a waterproof nylon fabric sheet, and a set of instructions.

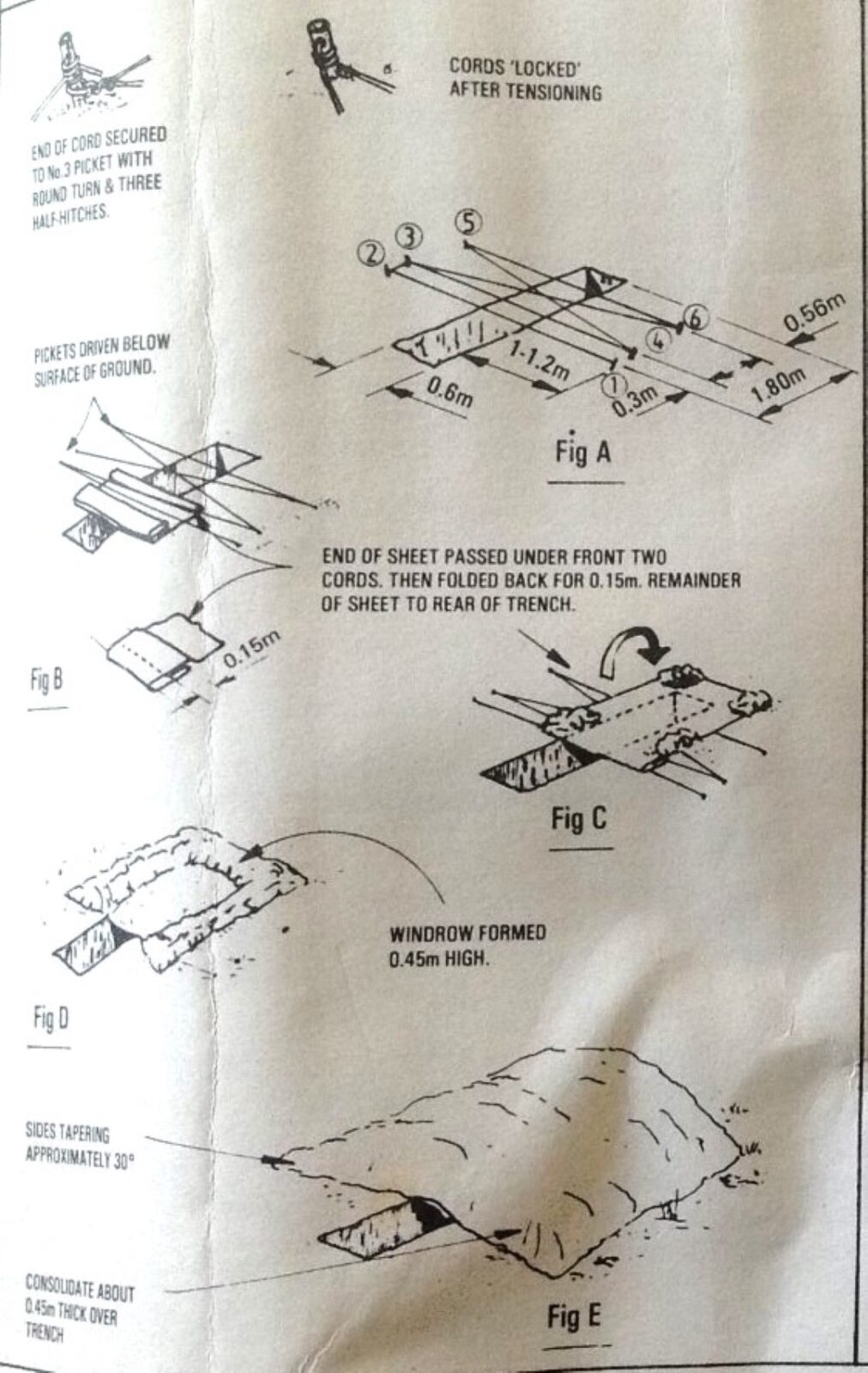

The IPK could be used a single.

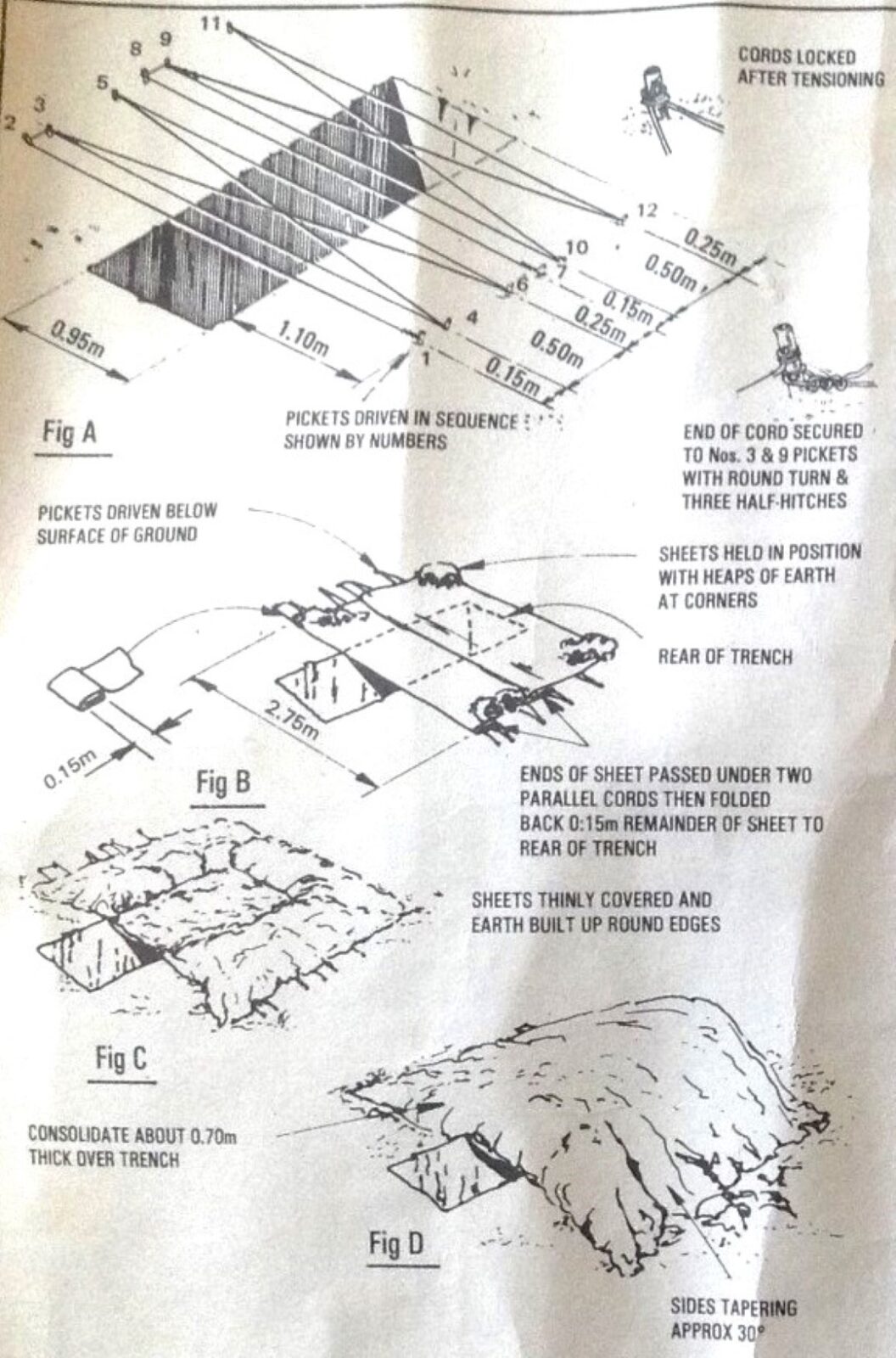

Or double.

But the principle was the same.

The pegs and cord created a lattice type supporting structure over the trench, and these had to be installed to a specific set of instructions.

The cover was sheet then placed on top of the cordage

And spoil from the trench placed on top to a depth of 450 mm.

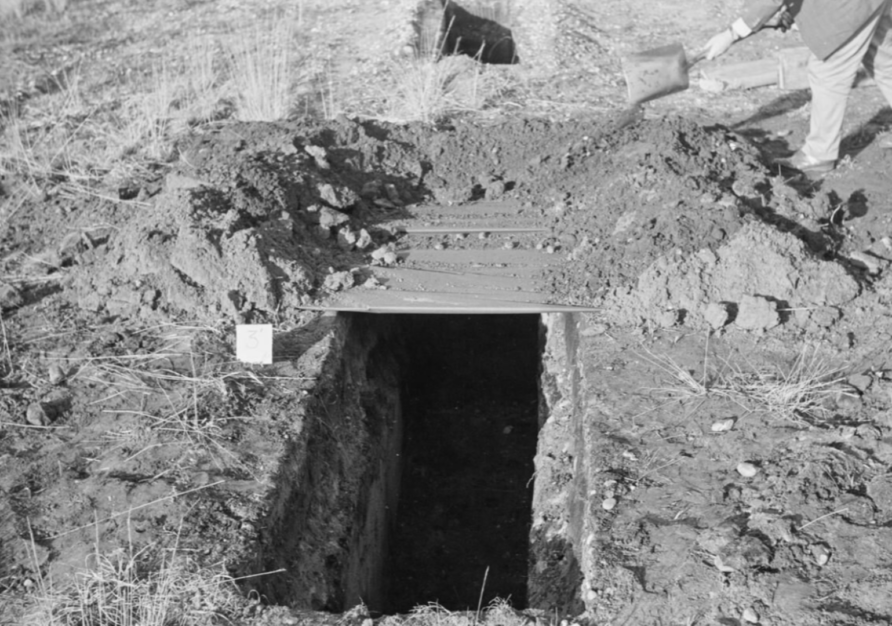

Testing was completed with some hefty chaps

And test weights.

The IPK was withdrawn from service several years ago on safety grounds, following several collapses, but i principle, it was a lightweight means of providing overhead protection that could be easily carried and used.

Can it be Modernised?

If it can be made lighter, more effective, safer to use, or more reflective of modern threats, it is perhaps worth exploring.

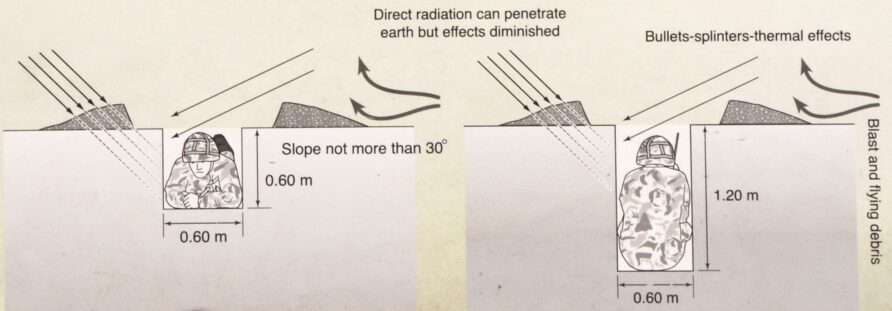

Going back to first principles, there is a minimum for very limited protection.

In the prone position, assuming the soldier is 2m long, the amount of excavated material is approximately 0.75m3. In the crouching position, assuming the soldier occupies a base width of 1m, the amount of excavated material is about the same. There is no advantage from either, at least in excavated material terms.

No defence stores are needed, just something to dig with, similar to a shell scrape.

Obviously, an overhead burst is not going to help, and because the excavated material is not contained, any protection above the excavation will be limited by the angle of repose of it.

Using Defencell Ranger would provide for greater protection.

As can be seen from the image, when folded, they are very compact and light. These are 1,200 mm long, 600 mm wide, and 600 mm high, for a volume of 0.43m3. But, at least three would be needed, so don’t improve on the excavation, and would need twice the fill material.

In some cases, they might be a better option, especially where soil conditions prevent even a shallow excavation, but they are still weight and volume on the soldier.

And, neither does it provide any overhead protection.

Back to the drawing board.

There are three components of the IPK, cordage, sheet, and picket.

Together, the cordage and picket provide a tensioned ‘roof truss’ of sorts.

The sheet is then secured in a specific way across the lattice of taut cordage, such that it self-locks, in many ways, it is a very clever design. The windrow formed 1m either side of the trench also provides top down force to prevent slippage, before the additional excavated material is placed on top to a depth of 450 mm.

It is these three components, used in a very specific arrangement, that stops collapse, and arguably, one of the downsides of the IPK.

Deviation from the defined method and dimensions could be hazardous.

If we approached this by seeking improvements in IPK components, but keep the same basic concept, there are probably better options available now.

Cordage

A lightweight but high strength and low stretch material like Dyneema, sheathed with polyester would be both stronger and lighter.

Sheet Material

Dyneema fabric, ripstop, or even Tyvek might all provide lighter and stronger materials to create the cover sheet with.

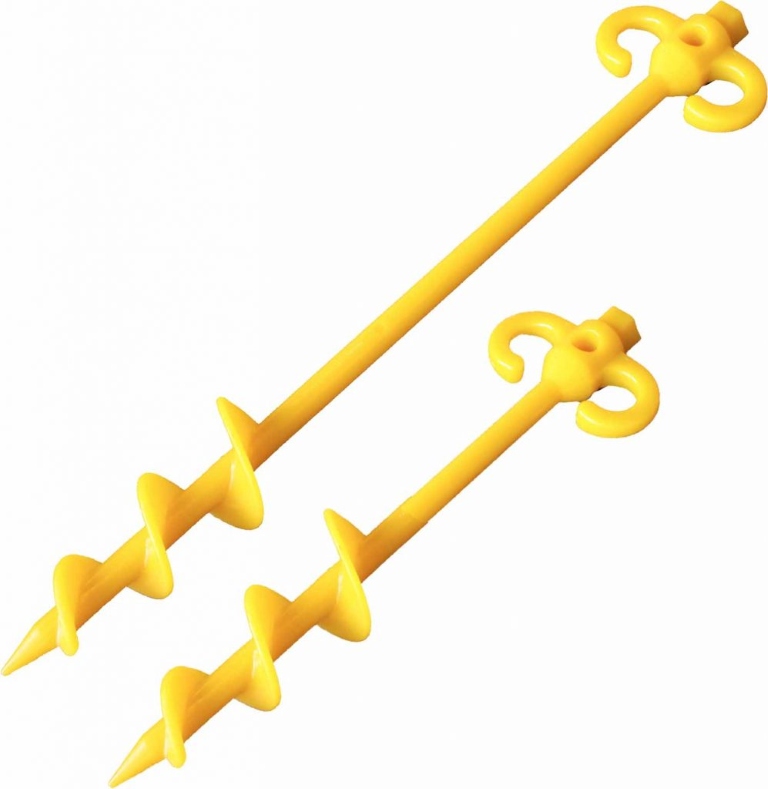

Titanium or plastic pickets (or tent pegs) would also reduce weight

There are also a range of screw in pegs that are well suited to a wider range of soil types.

These also have a hex head to assist with driving, by hand or with a power tool (if available)

Standard knots and lashings would still be required to tension the cordage, but to reduce skills required, and possibly improve safety in doing so, a cord tensioner could be used.

Taken together, these would still use the same concept, but potentially offer improvements in durability, strength, and safety,

One alternative would be to dispense with the cordage, and tension the fabric directly, relying on this tension to provide cave in resistance.

Eyelets could be woven in, and the fabric reinforced with suitable cordage, or a gripper of sort used.

Tensioning would be a challenge, though, I think.

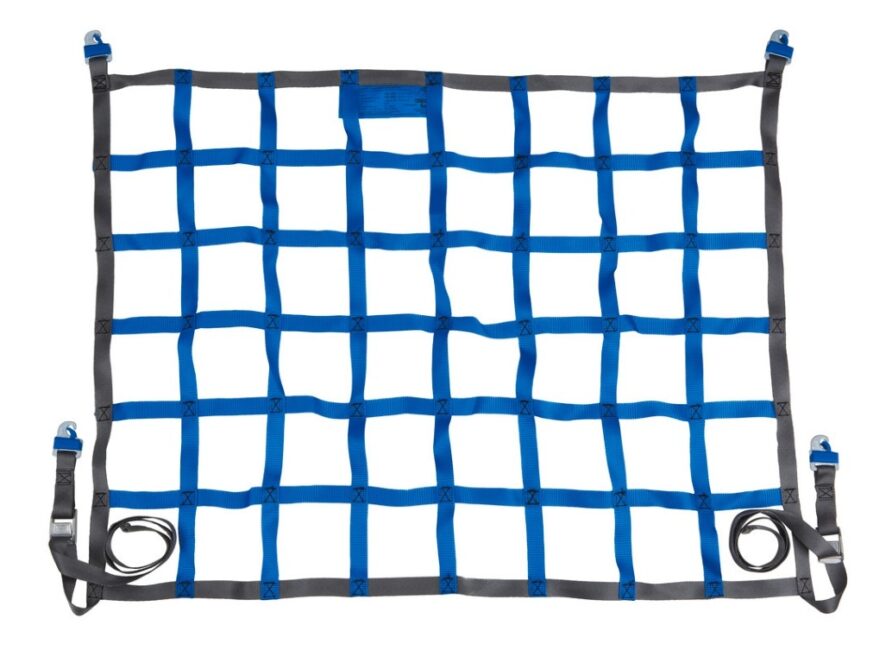

Fall safety net is another option, covered with a very lightweight plastic sheet to prevent water ingress.

The same with webbing or cargo nets.

Both these would be heavier than the simple cordage lattice, but would allow a much thinner and lighter sheet to be used, and have integral tensioning fixtures.

We could also look at lightweight collapsible poles to provide the strength component, thus eliminating the need for tensioned cordage.

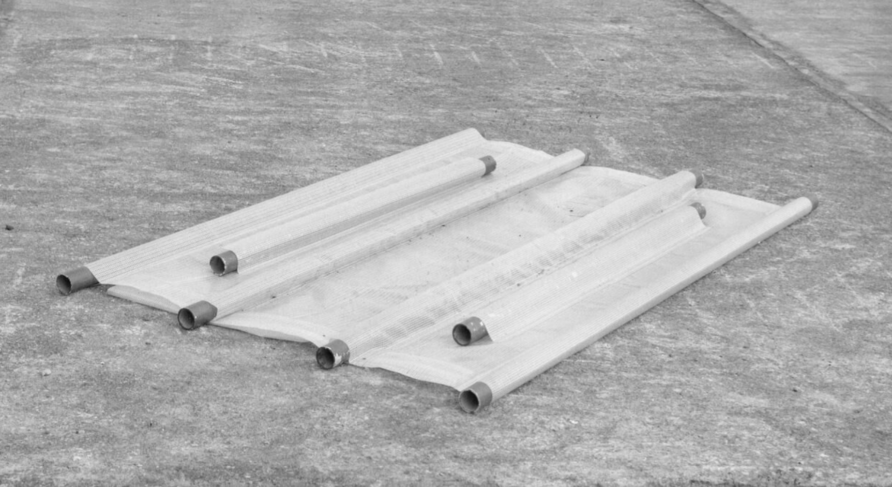

I am reminded or this concept from MEXE in the seventies.

Using sewn in steel tubes and canvas, they were used to for overhead support (the shorter posts were placed transversely)

With additional protection added. Tests went well, but they did not at the time offer any significant advantages over pickets and CGI.

It is obviously not suitable as an IPK replacement due to weight and bulk.

But, what if we replaced the heavy canvas with lightweight Dyneema or Tyvek, and the steel poles with collapsible carbon fibre?

Carbon fibre tubes, box section, octagonal or oval, are readily available.

Even perforated for that last bit of weight reduction.

They can be found in everything from tent poles.

To camera tripod and even walking sticks!

They are generally designed to take longitudinal loads, but bend resistance can be improved with specific weave patterns and strand orientation.

This approach would completely negate the need for pickets and pegs, cordage and tensioners.

The collapsible pole would be inserted into a pre-sewn tubular pocket in the selected fabric and placed across the trench, as the concept from MEXE, although a little smaller.

Excavated material would then be placed on top to provide protection.

What About Drones

A good question.

In a contemporary operating environment, would some sort of camouflage or drone mesh provide a more relevant form of lightweight protection for the individual soldier?

Instead of cordage, the mesh, or webbing panels above could potentially serve a dual purpose, especially when combined with the carbon fibre poles.

Summary

The IPK was very much a Cold War concept, crash out, dig to stage 1, and if time permitted, build out to the more sturdy 2 and 4 man battle trench.

The world has moved on, not only are the basic components available in stronger and lighter forms, but materials like carbon fibre tubes might allow other design approaches to be pursued.

The threat environment has also changed significantly.

One subject I have touched on a few times in this series is avoiding detection in the first place.

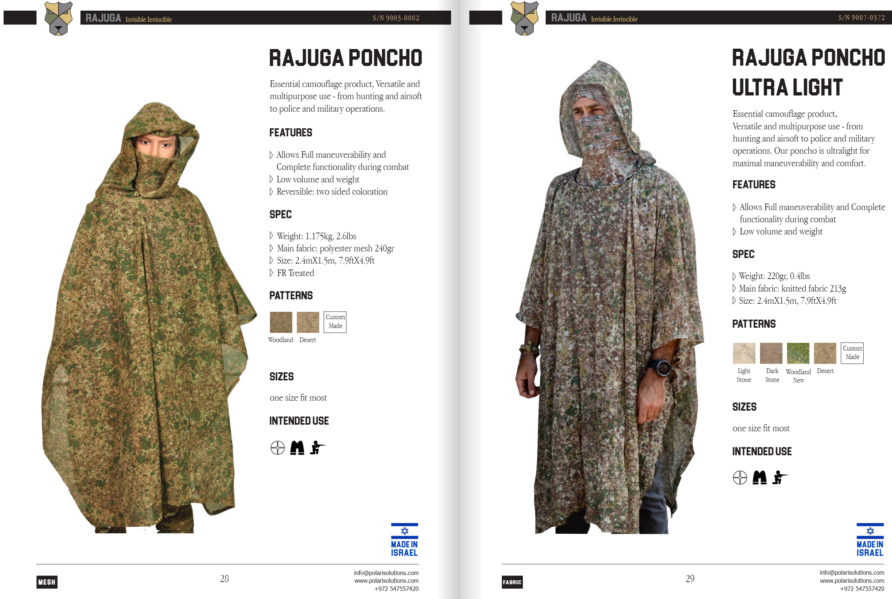

Fibrotex, Saab, and Polaris, all make some thermal concealment fabrics for individual soldiers, vehicles and fixed locations.

Backpack covers, capes, and even ponchos are all now available in multispectral camouflage materials.

We rightly spend significant sums on weapons, sights, communications, and protection for individual soldiers.

Taking an integrated approach, it should be possible to select materials and components, combined with smart design, that provides a combination of all three for the individual soldier or pair.

Detection avoidance, counter UAS screens, and even support for overhead protection in a hastily dug hole in the ground.

I might even be tempted to say system of systems!

Leaving the (overburdened 🥵) infantryman aside, I would look at crews that will have to fight from semi-fixed positions, like towed artillery, mortar crews and AD.

Weight becomes less of an issue, and as dispersion is a well-drilled technique against total destruction, a way to stay in the fight against the use of area cluster munitions should get some attention.

Kevlar riot shields would give good top cover, are light and easily stackable

… Digging can't be avoided, but the ways to keep them in place have been amply described in the lead-in article

A thought occurs that a trek cart with a ballistic material for a chassis could serve to provide cover as well as portage for crew served weapons.

Also that an individual kit could include a couple of composite spars, like tent poles, that could be strung like a bow to provide an arch, where the preload would get you stiffness without as much mass/volume as you'd need with simple straight poles. This approach would make a cover less sensitive to pegging out and tensioning, but unless you added a bunch of cross spars you'd need to be careful about how you build up the earth layer.

One wonders how easy it would be to vacate a position with your IPK, or if you'd expect new ones coming up with the food and ammo.