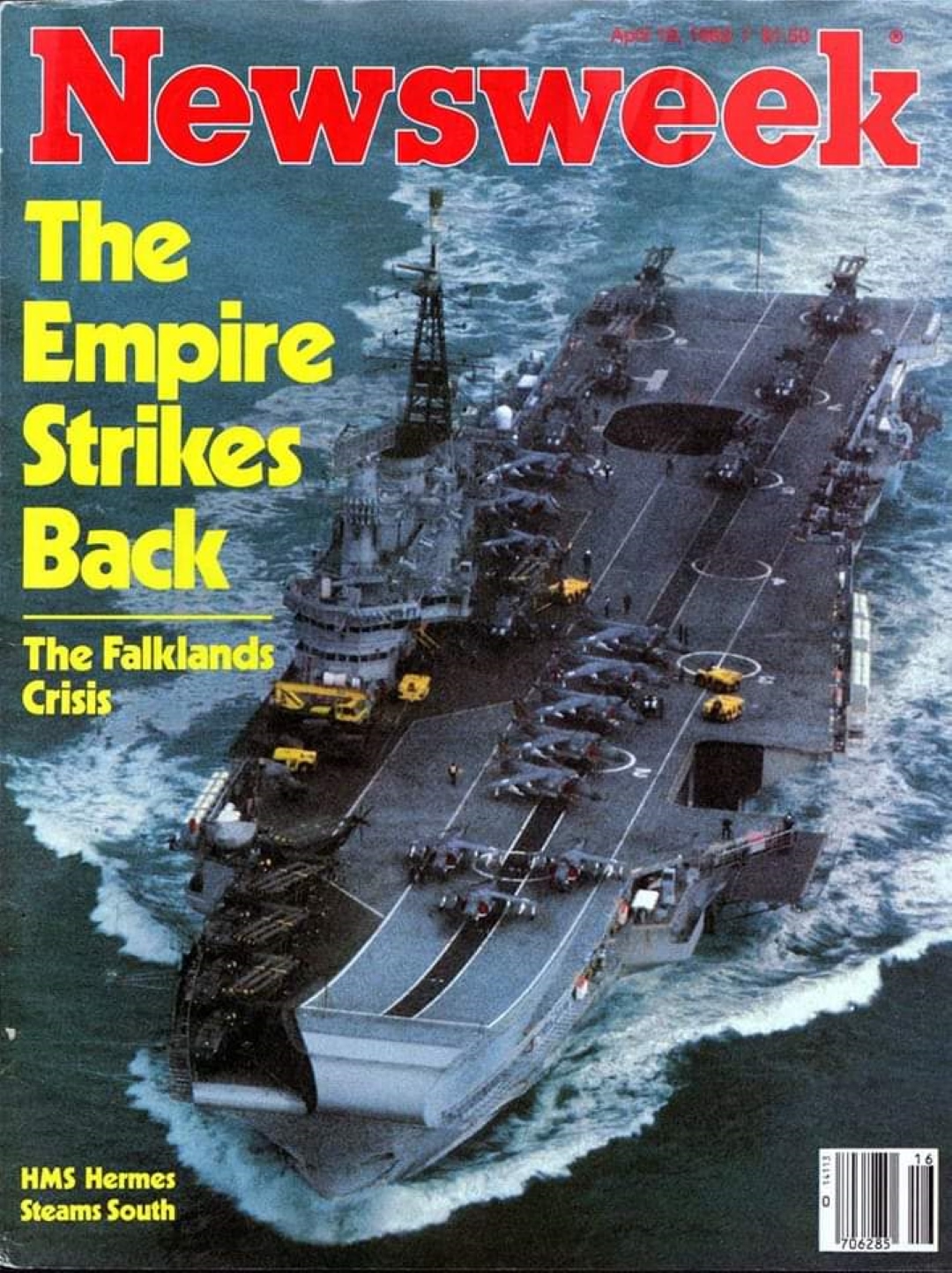

The airport at Port Stanley on the Falkland Islands played an important role in life on the Falkland Islands, before, during and after the 1982 Conflict.

The most significant point in the airports’ history was arguably the Black Buck raids.

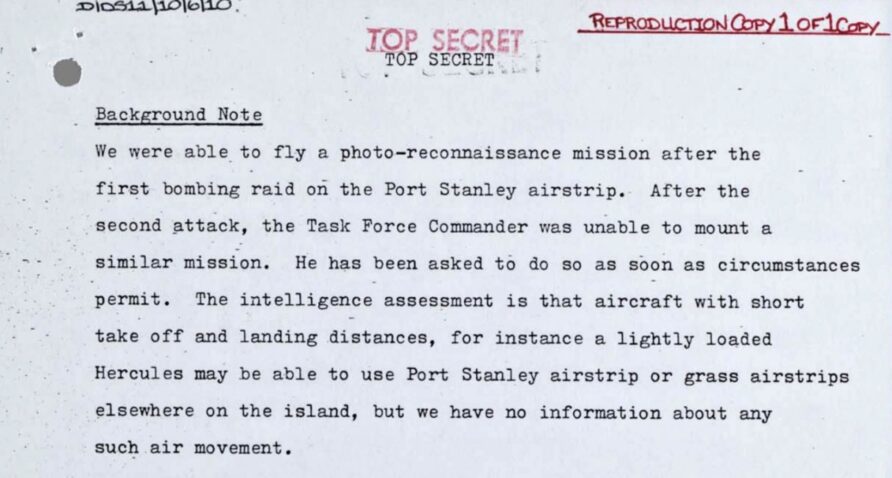

The 1982 Black Buck raids were a series of seven long-range bombing missions conducted by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Falklands War. These missions were aimed at attacking Port Stanley airport in the Falkland Islands, which was under Argentine control at the time.

The raids involved the use of Vulcan bombers, supported by Victor tanker aircraft for in-flight refuelling.

The first raid, known as Black Buck 1, took place on April 30, 1982, with the objective of damaging the runway at Port Stanley to prevent its use by fast jets.

The raids were notable for their complexity and the distance they covered, with the round trip between Ascension Island and the Falklands being almost 13,000 kilometres.

Despite the technical challenges and the operational difficulties encountered, the Black Buck raids are considered a significant achievement in terms of planning and execution.

However, their impact on the outcome of the war is a subject of debate, with some sources highlighting their limited physical impact and questioning their strategic value.

The raids demonstrated the RAF’s capability to conduct long-range bombing missions and showcased the skill and bravery of the pilots and aircrew involved.

However, the effectiveness of the raids in terms of their impact on the conflict remains a point of contention with main claims and counterclaims.

In all the commentary, not much of it looks at the engineering aspects of the runway.

Before the 1982 Conflict

Before the 1982 conflict, aviation on the Falkland Islands was increasingly important to the health, wealth, and well-being of the islanders.

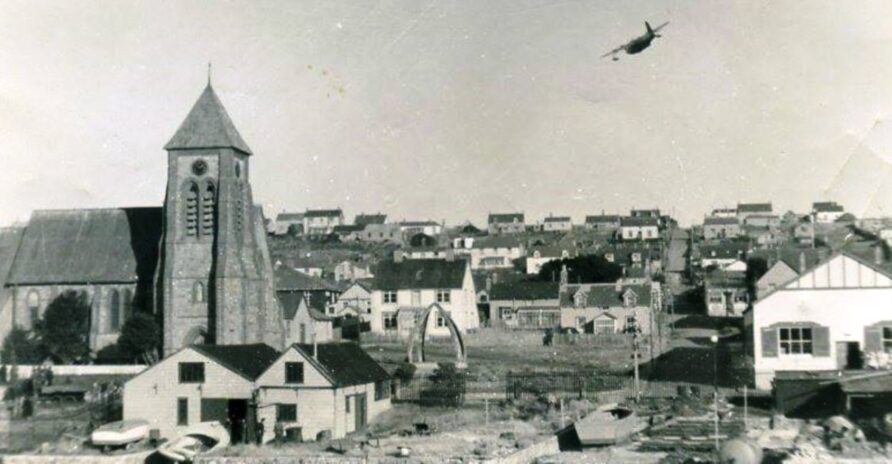

During WWII, many seaplanes visited the islands, this Sunderland for example.

The image below shows a Falkland Islands and Dependencies Aerial Survey Expedition (FIDASE) CANSO flying boat, sometime between 1955 and 1957, on its way to Deception Island.

The two PBY-5A CANSO aircraft were provided by the Hunting Aerospace Surveys Ltd company.

In 1944, the new Governor of the Falkland Islands, Miles Clifford, proposed that the Australian Flying Doctor Service would be an ideal model for a new aviation service on the islands, reportedly, after reading about it in a Reader’s Digest on his journey south.

A pair of ex-RAF Taylorcraft Austers were located, purchased for £700 and shipped to the islands on the RRS John Biscoe in 1948.

G-AJCH and G-AJCI became VP-FAA and VP-FAB.

After reassembly at Stanley Racecourse, they were flying by March 1949.

Their first operational use was in transporting a child named Sandra Short with peritonitis from North Arm in East Falkland. The mission was a success, the young patient was saved, on Christmas Day.

Suitable landing strips on the Falkland Islands were uncommon and after a rough landing at San Carlos, one of the Austers was damaged. After repair, it was converted to a float plane.

After the Austers, the Falkland Island Government Aviation Service (FIGAS) made use of a second-hand Canadian Noorduyn Norseman 5 float plane.

At this point, floatplanes were still the preferred option. When this became unserviceable due to corrosion, it was replaced with a DHC-2 Beaver, operated from 1955 to 1956. After an accident, it was replaced with another Beaver that flew until retirement in 1967.

Because most of the settlements were near the sea, the float plane enabled air transportation without creating runways, but in many instances, sea conditions made landing impossible.

The aircraft were hangared near a launch ramp, near Port Stanley. The same hangar would be used to store Argentine war dead in 1982.

The first notable Argentine aviation-related incident came in 1964 when Miguel Fitzgerald flew a Cessna 185 to the Falkland Islands and landed on Stanley Racecourse.

Recounting his flight, Miguel said;

Several times I had to abandon my attempt to fly to the Falklands for various reasons. If I had announced my intention, declaring on the flight plan, I would not have been allowed to leave. The same day I turned thirty-nine years, I kissed my wife and my children walked me to the plane “Cessna 185” whose seats had been replaced by fuel tanks and which had a radio-telephone. With chocolate and coffee supplies, the flight to Rio Gallegos, capital of Santa Cruz province , was completed, followed immediately toward the Malvino archipelago, which is a five hundred and fifty kilometres.

Navigating between clouds, I noticed some clearing that enabled me to fix the status of the islands, orienting between West Falkland and East Falkland when I saw the San Carlos channel. The British flag flew over the governor’s residence, showing the wind direction, which I used to land, after circling. I landed on a horse racing field…

I immediately hoisted the Argentina flag on a pole. Five people came and asked me in English if I wanted or needed anything. Ten minutes later, I got up again to address the flight to Rio Gallegos, my desire fulfilled.

The aircraft is currently in a museum.

Not amused, the Colonial Secretary, Mr WH Thompson, ordered the racecourse be furnished with obstructions for when not in use.

Unfortunately, they were removed sometime later.

Two years later, the racecourse was to see another unwanted aircraft visitor.

A short time after the World Cup quarter-final defeat of Argentina by the England team, on September 28th, 1966, a group of Argentine radicals (Condor Group) hijacked an Aerolíneas DC4 and forced the pilot to fly to the Falkland Islands.

The group included eighteen members of the metalworkers union and a journalist named Dardo Cabo.

There is some dispute about whether they knew Stanley had no runway or not, but when it arrived, the pilot executed a very skilled landing on the short racecourse.

Three Falkland Islanders went to assist but were taken hostage, although, in some accounts, the hostages were Royal Marines.

Soon after, the aircraft was surrounded by a fully armed contingent from the Falkland Islands Defence Force and Royal Marines. Later that day, the hostages were exchanged for the Royal Marines Captain, Ian Martin, and local Police Sergeant, Terry Peck.

Using a familiar tactic, the island’s defenders took to ostentatiously demonstrating the value of copious amounts of warm food and tea, whilst the erstwhile invaders shivered under the wing as the temperature plummeted.

After thirty-six hours, common sense and a helpful intervention from a local Catholic priest named Father Rodolfo Roel ended the stand-off. The aircraft did not have enough fuel for the return leg and was bogged in, but this was soon rectified, and the aircraft was sent on its way, the hijackers repatriated on board the ship Bahía Buen Suceso.

Carbo was arrested when back in Argentina and served three years in prison, eventually executed by the Junta in 1972.

The others served shorter sentences.

The incident resulted in an increase in the size of the Royal Marines contingent on the island, Naval Party 8901.

The final incursion occurred in 1968, Señores Fitzgerald again. This time, he flew a twin-engine Grand Commander, owned by the Daily Chronicle.

Because the racecourse had been blocked, he was forced to land on Eliza Cove Road, damaging the aircraft in the process.

Video

The aircraft and its passengers (after spending 48 hours in a cell) were repatriated to Argentina by HMS Endurance.

Both countries agreed that part of a normalisation process would require improved transportation links.

Following a few exploratory flights by the FAA, Líneas Aéreas del Estado (LADE), the Argentine military airline, operated a Grumman Albatross amphibian aircraft service to the Falklands using Albatross aircraft from February 15th, 1971, the first flight being a medical evacuation for a critically ill sailor.

The first passenger flight was on July 3rd and on the 15th the ‘Communications Agreement’ was signed to regularise traffic on a two-weekly basis.

This link provides a good account of the 1971 Agreement

The next stage was the construction of a runway.

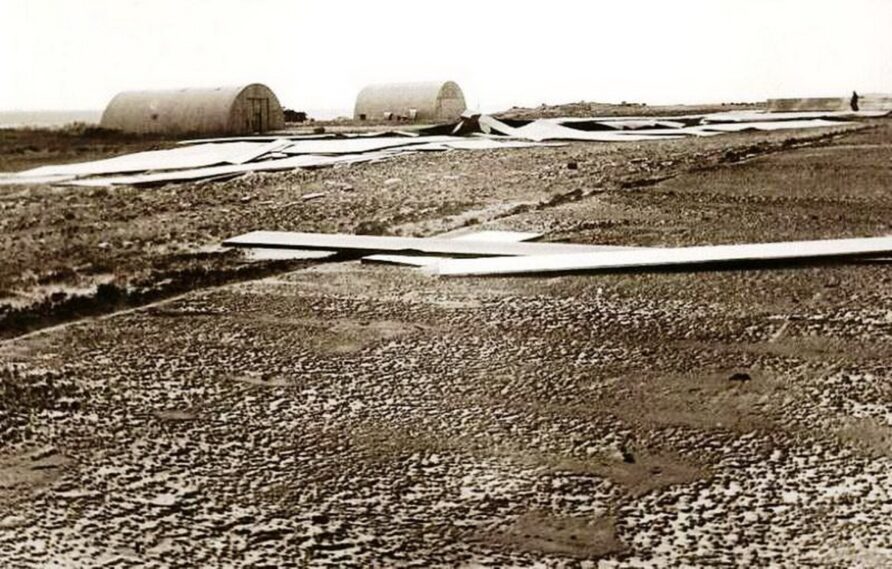

After the signing of a communications agreement, the UK and Argentina agreed to build a temporary runway to the South of Stanley, at Hookers Point.

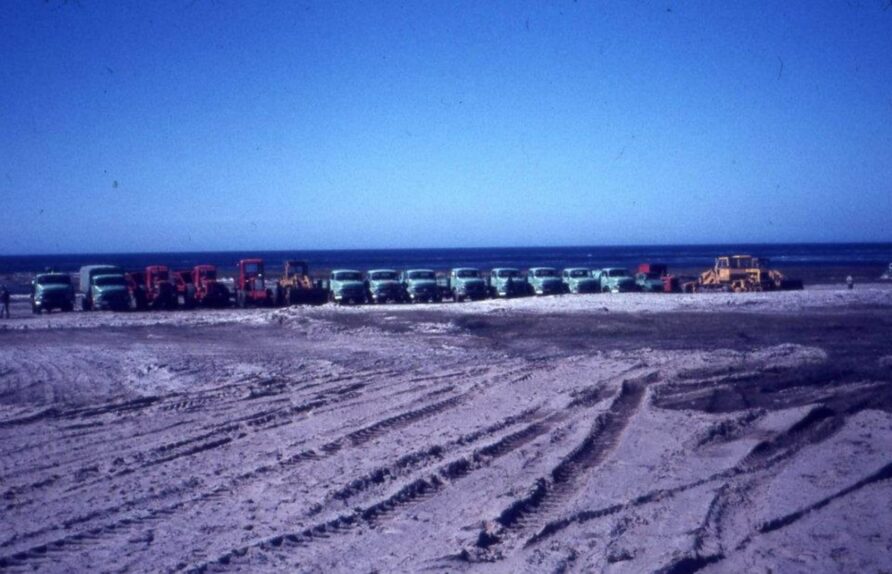

The temporary runway at Hookers Point was constructed by Grupo I de Construcciones de la Fuerza Aérea (FAA) using aluminium matting from the Harvey Aluminium Co in the USA, it was 730m long by 20m wide, extended to 800m at a later point.

A couple of small outbuildings supported basic maintenance and storage. The agreement called for the UK to fund the construction materials (including $1m for the matting) and Argentina to provide labour and plant.

Stanley Airport’s (Hookers Point) first landing took place on the 16th of November 1972, a Fokker F-27.

Video

On the first anniversary of the runway at Hookers Point being operational, a delegation from Argentina landed.

As can be seen in the image above, the Sunday best uniforms were out and in a US Marine Corps Staff Paper titled Offensive Air Operations of the Falklands War, Major Walter F. DeHoust recalls;

The Argentine officials proceeding on the first flight of the air service turned out to be Argentine senior military officers in full uniform. Hearing of this, the Falkland Islands’ governor, Toby Lewis, was ordered to hoist the Union Jack and appear at the ceremony himself in full dress gubernatorial regalia.

The islanders themselves feared that ceremonially clad Argentines represented a covert invasion, perhaps even supported by the British Foreign Office.

The islands’ secretary, John Laing, felt a demonstration was likely and called out the Marine guard, a permanent detachment of military stationed on the Falklands to maintain order

In what will become significant later, the new runway was extended to 800m using additional AM-2 aluminium matting, works completed in October 1976.

The occasional C130, Learjet and FMA IA50 Guaraní flights were made, and the service continued for several uneventful years until transferred to Stanley Airport.

Hookers Point remained operational after Stanley Airport was built for temporary and emergency use until May 1978 when a storm scattered many of the aluminium matting runway panels.

A solution to the problem was already well underway, a permanent runway East of Stanley at Cape Pembroke.

The £4.2 million build contract was awarded to Johnson Construction in 1973 with the first works on drainage commencing in 1974. The runway was to be 1,200m long, 45m wide and constructed to a standard that would allow Fokker F-27 Friendship and Hawker Siddeley HS 748 to land.

It had a minimum Load Classification Number (LCN) of 16 although in places it was as high as 30, 300 mm of compacted crushed stone on white sand with a minimum of 32 mm of asphalt.

A single airport terminal building and parking apron were also built, in addition to a number of smaller storage buildings.

The islanders knew full that by failing to build longer and stronger, they would be dependent upon Argentina, a position no better than the runway at Hookers Point.

An extension was proposed but denied for political reasons, despite it being of modest cost.

Discussions between the Falkland Islands Legislative Council and oil exploration companies commenced in Stanley, followed by the Daily Chronicle in Argentina launching an appeal fund for an invasion of the islands!

The diplomatic and public mood towards the UK and Falkland Islands darkened, with more or less open threats of invasion. On the 5th of February 1976, the Argentine frigate Almirante Storni fired shots across the bow of the RRS Shackleton 78 miles (ca. 126 km) South of Stanley.

A 1976 review by the Falkland Islands Government Aviation Service (FIGAS) concluded that given the by now widespread availability of grass airstrips at most of the settlements, the floatplanes should be withdrawn and replaced with larger, land only aircraft. The aircraft selected was a Britten-Norman BN-2A-27 Islander.

Conventional landing aircraft were also much cheaper to maintain than floatplanes.

On the 17th May 1978, the first Fokker F-28 Fellowship landing at Stanley.

Flights took place before the airport was officially opened on May 1, 1979, by Sir Vivian Fuchs, the first ‘official’ landing was by a local named Jim Kerr in a Cessna 172.

The first jet aircraft to operate from the Falkland Islands was a LADE Fokker F28 Fellowship.

Stanley Airport then became the home for the remaining Beavers and new Islanders of the Falkland Islands Government Air Service (FIGAS).

The first Islander was brought into service by FIGAS in 1979, VP-FAY.

In the same year, an employee of the Scottish operator Loganair surveyed the grass airstrips of the Falkland Islands.

He found 41 grass or hard sand landing sites, all of ‘good to excellent quality, with suitable drainage for extended operation times. By the end of the year, FIGAS had carried just under four thousand passengers.

There were several reports that Argentine military pilots flew both as passengers and pilots on the regular LADE flights, but of course, these were ignored.

15 years of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office trying their hardest to appease Argentina at the expense of the Islanders came to a head in December 1980, a report in the Times noting;

The House of Commons came together in total concord yesterday to voice its deep suspicion of the intentions of the Foreign Office and of Mr Nicholas Ridley, a Minister of State, for the future of the Falkland Islands and their relationship with the Argentine.

Seldom can a minister have had such a drubbing from all sides of the House, and Mr Ridley was left in no doubt that whatever Machiavellian intrigues he and the Foreign Office may be up to, they will come to nothing if they involve harming a hair on the heads of the islanders.

The minister was left stammering and confused, as in vain he protested that nothing would be done, and no arrangement would be agreed with Argentina that had not been first endorsed both by the islanders and by Parliament.

Mr Ridley, who has just returned from a visit to the Falklands, could, not have received a colder welcome. MPs were quick to draw attention to the apparent contradiction between Mr Ridley’s assertion that the British Government had no doubt about our sovereignty over the islands and his proposal to the islanders that a solution might be found if they would agree to exchange the title of sovereignty against a long lease-back to Britain.

Another solution might be found by some method of freezing the dispute for a period, Mr Ridley added. It was essential, he added, that the Government should be guided by the wishes of the islanders and any solution must preserve British administration, law, and way of life while releasing the potential of the Falkland’s economy and maritime resources, which were at present blighted by the dispute.

Mr Peter Shore, the Opposition spokesman on foreign affairs, voiced the views of MPs of all parties when he told the minister that this was a worrying statement and that the proposal for a leasing arrangement was a major weakening of our long-held position on sovereignty in the islands.

To make that proposal in so specific and public a manner was likely only to harden Argentine policy and undermine the confidence of the islanders. From the Conservative benches, Mr Julian Amery told the minister that his statement was profoundly disturbing.

For years the Foreign Office had wanted to get rid of this commitment, although the islands had an important part to play in the future of the South Atlantic. Angrily, Mr Ridley rejected the suggestion that he was merely acting as the errand boy of the Foreign Office.

Viscount Cranbourne, another Conservative MP, told Mr Ridley that his statement had caused disquiet among his supporters and that by merely entertaining the possibility of surrender of sovereignty he was encouraging the islanders to think that they did not enjoy the support of their mother country.

From the Liberal benches, Mr Russell Johnston said that there was considerable doubt about Mr Ridley’s intentions. Shameful schemes for getting rid of the islands had been festering in the Foreign Office for years. Mr Ridley again protested his innocence and his good intentions to loud shouts of ‘no’.

A few moments later, Mr Ridley floundered into deeper water. when he was asked whether the Government would accept the views of the islanders if they opted for the maintenance of the status quo.

The minister seemed to many to be dodging the issue when he replied: ‘We shall have to wait to see how the situation develops’

The one certainty of yesterday’s exchanges for the Falkland Islanders was that if ever the ‘festering plots’ of the Foreign Office should reach the floor of the House of Commons, they will be given very short shrift

June 1981 saw an overflight of South Georgia by an FAA C-130 Hercules, and continued prevarication and mixed messages from the British Government, for example, the announcement of the withdrawal of HMS Endurance, HMY Britannia got a refit, though.

I can confirm that HMS “Endurance” will be paid off in 1982 on her return to the United Kingdom, following her deployment in the South Atlantic and the Antarctic Region later this year.

There are no plans to replace her. However, the Royal Marines garrison in the Falkland Islands will be maintained at its present strength, and from time to time, Her Majesty’s ships will be deployed in the area.

Lord Trefgarne, Foreign Office Minister, 30th June 1981

And despite the political environment becoming increasingly toxic and the likelihood of a military action equally obvious, flights continued, like this one in 1981

Until the occupation, LADE carried 465,763 passengers and 21,597 pounds (ca. 10 t) of cargo between the Falkland Islands and the mainland, amassing 3,553 hours.

On March 11th, 1982 an Argentine Air Force (FAA) C130H made an ‘emergency landing’ at Stanley Airport but were out within the hour, and another landing, by an FAA Learjet followed on the 19th

Both raised eyebrows but also ignored, there were clearly reconnaissance and proving flights. The last three scheduled LADE flights in Stanley Airport took place on 16th March, 23rd March and 30th March 1982.

On the evening of the 1st of April 1982, one of the FIGAS Islanders was flown to the racecourse in readiness for a first light recce but events of the early hours of the 2nd made this moot, it was flown back to Stanley Airport.

By the beginning of the conflict, the Falkland Islands had many grass airstrips and a permanent runway with associated facilities.

Importantly, there was also a large stock of aluminium airstrip matting on the island and the local forces knew full well both the importance of the runway and that Argentine forces were both intimately familiar with and had augmented this with aircraft-specific reconnaissance flights.

Conflict

By the beginning of April 1982, the invasion was imminent and expected.

Vastly outnumbered, the Royal Marines and Falkland Island Defence Force deployed two personnel to the beach at York Bay with barbed wire and a GPMG, the runway at Stanley Airport was blocked with vehicles and the directional beacon switched off, and a section deployed to the Airport.

Invasion

The Argentine invasion plan emphasised overwhelming force to convince Naval Party 8901 to surrender without fighting.

Landing Force (Task Unit 40.1) comprised 904 Marines and soldiers in a combined arms unit with engineers, artillery, air-defence units and amphibious armoured vehicles.

Although it was a combined force, the majority were Marines, with only 39 from Ejercitos 25h Infantry Regiment.

The landing force was in possession of ample intelligence on Stanley Airport and the surrounding areas.

At 5.30 am on the 2nd April, Admiral Busser sent a message to the Landing Force, the invasion was about to move beyond the point of no return;

I am the Commander of the Landing Forces, made up of the Argentinean Marines and Army on this ship, of units aboard the destroyer Santisima Trinidad and the icebreaker Almirante Irizar and the divers onboard the submarine Santa Fe. Our mission is to disembark on the Falklands and to dislodge the British military forces and authorities installed there. That is what we are going to do.

Destiny has wished us to be the instigators of making good the 150 or so years of illegal occupation. In those islands, we are going to come across a population with whom we must develop a special relationship. They live on Argentine territory and consequently, they must be treated as though they are living on the mainland.

You must be punctilious in respecting the property and integrity of each of the inhabitants.

You will not enter into any private residence unless it is necessary for reasons of combat.

You will respect women, children, old people and men.

You will be hard on the enemy, but courteous, respectful and pleasant in your dealings with the population of our territory and with those we have to protect.

If anyone commits rape, robbery or pillage, I shall impose the maximum penalty. And now, with the authorization of the Commander of the Transport Division, I am sure the Landing Force will be the culmination of the brilliant planning other members of the group have already achieved.

Thank you for bringing us this far, and thank you for landing us tomorrow on the beach. I have no doubts that your courage, honour, and capability will bring us victory. For a long time, we have been training our muscles and our hearts for the supreme moment when we shall come face to face with the enemy.

That moment has now arrived. Tomorrow you will be conquerors. Tomorrow we shall show the world an Argentine force valorous in war and generous in peace. May God protect you! Now say with me, Long live the Fatherland! (Operacion Rosario)

Operation Virgin del Rosario started in the late evening of April 1st, 1982 when Argentine special forces landed at Mullet Creek.

The first wave consisted of four LVTP-7’s, the second, fifteen Amtracs and the final wave, five LARC’s and a recovery LVTP-7.

Follow on forces were to land a short while later and to the North of Stanley, after a special-forces team landed from the submarine Santa Fe, the main force came ashore at Yorke Bay, pushing through the dunes and on to the airport.

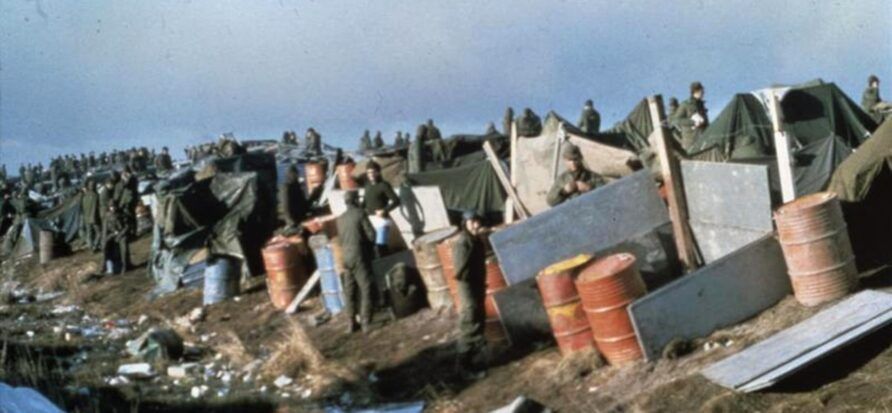

The airport was quickly occupied and the task of clearing the runway obstacles began.

After a stiff firefight, Governor Rex Hunt ordered the Royal Marines to surrender.

One Argentine Marine later died from his wounds, and two others were seriously injured.

Don’t make yourself too comfy, mate, we’ll be back.

Unknown British Royal Marine (as leaving, to Argentine guard)

The first Argentine aircraft to land at the airport was a Sea King, 2H-231, landing at 07:34.

Later that morning, ARIES 82 (FAA air bridge) commenced, the first aircraft into Stanley Airport was a C-130(H) (TC-68) landing at 08:45, followed by two F-28’s from Comodoro Rivadavia, carrying personnel of the 25th Infantry Regiment and a number of FAA specialist personnel.

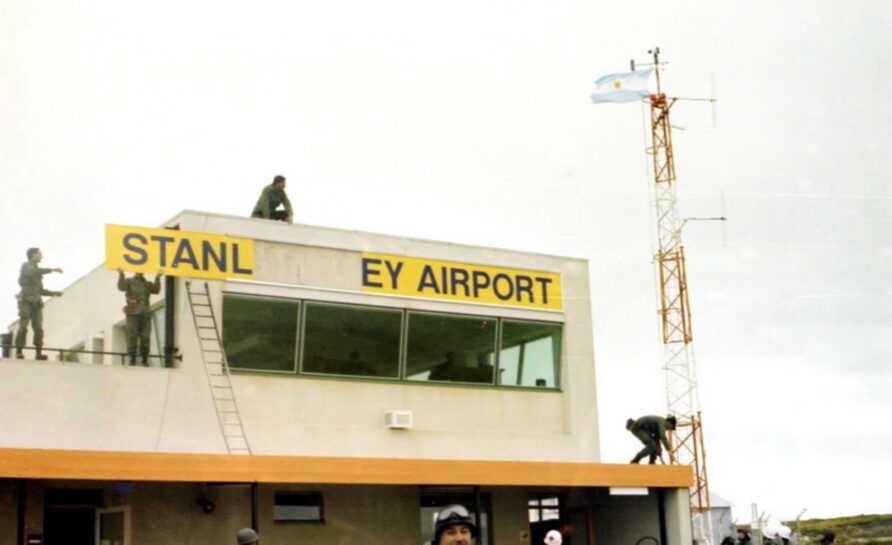

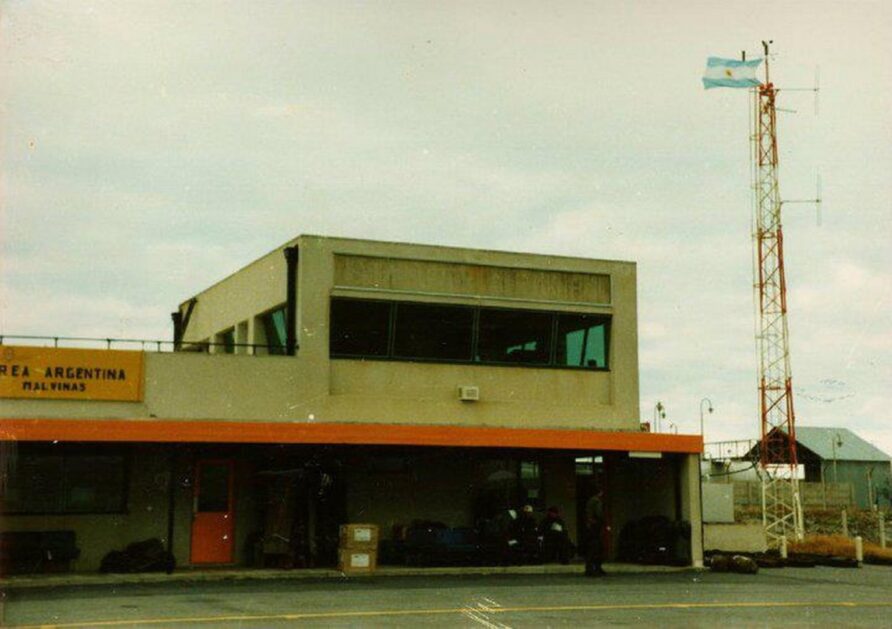

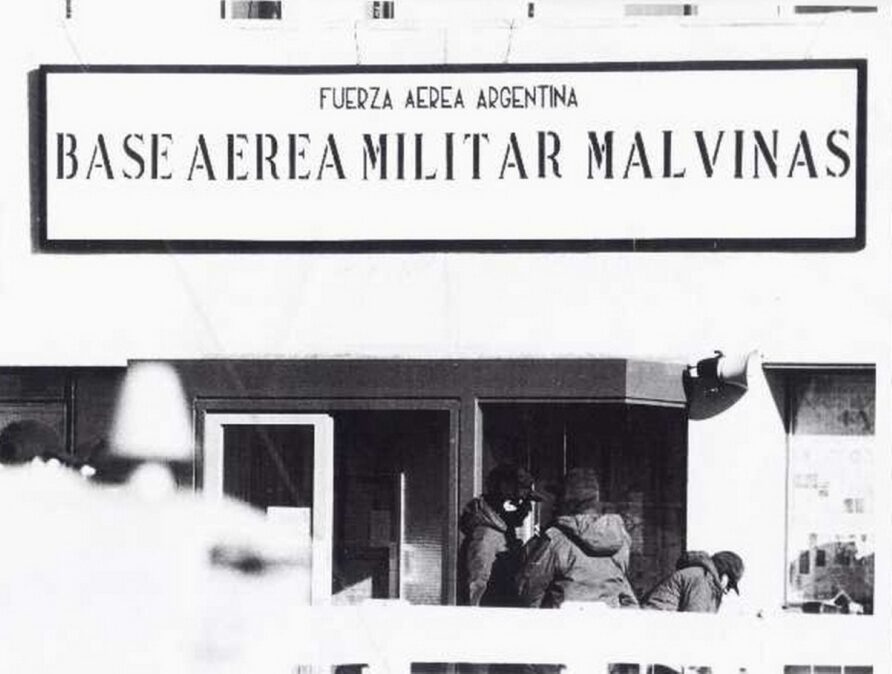

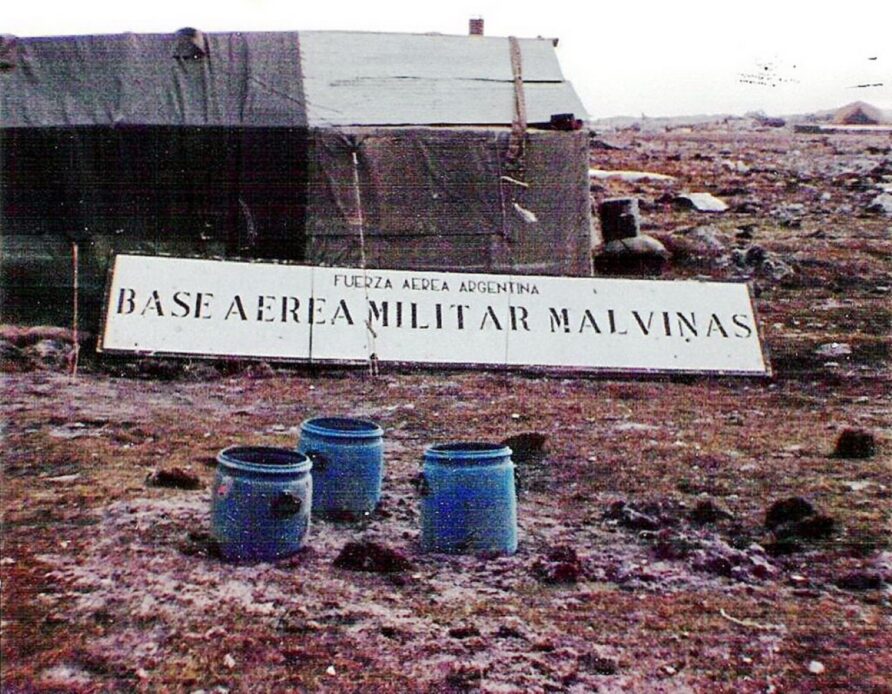

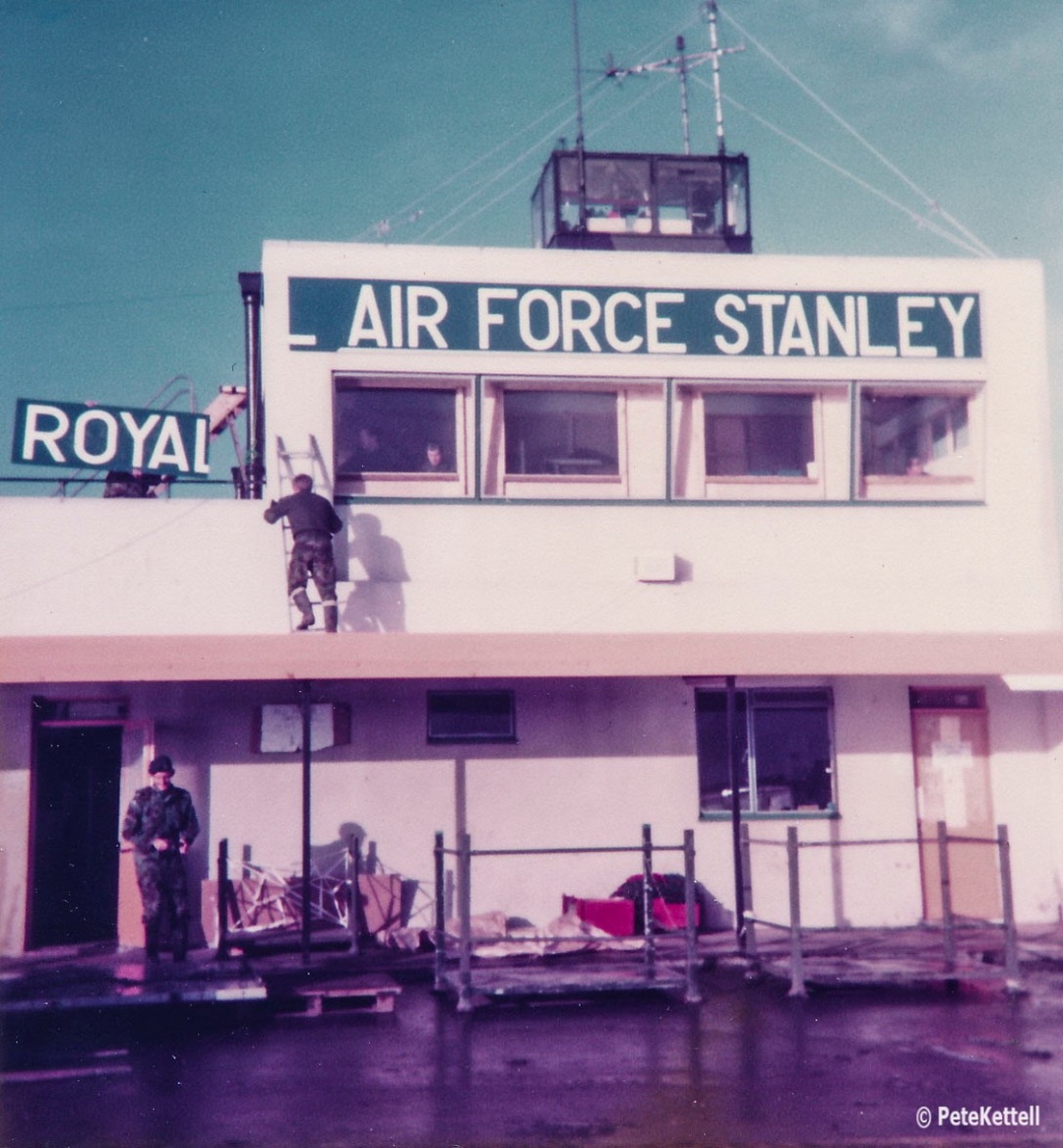

The ‘La Estación Aeronaval’ was established with the Argentine flag raised, preparations were quickly made to change the signage.

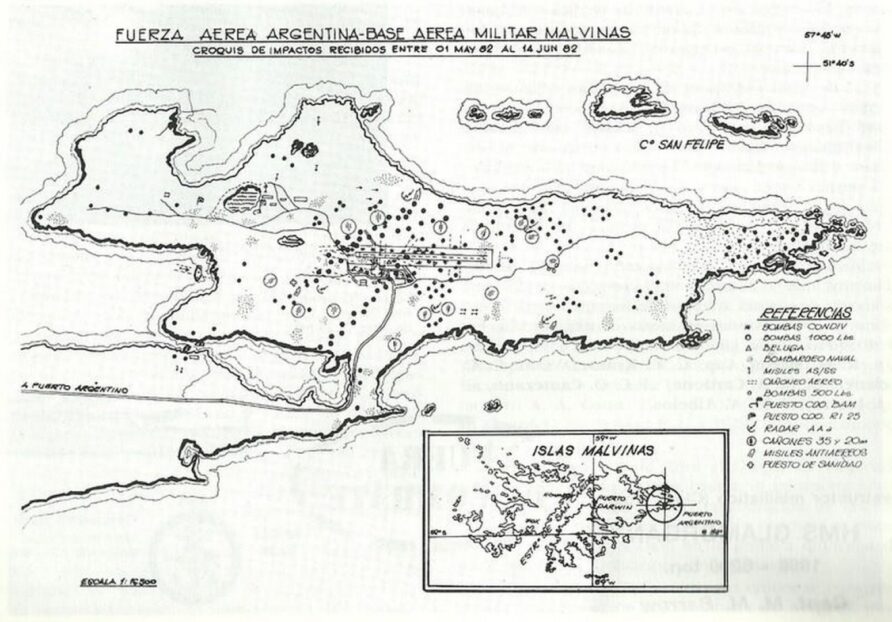

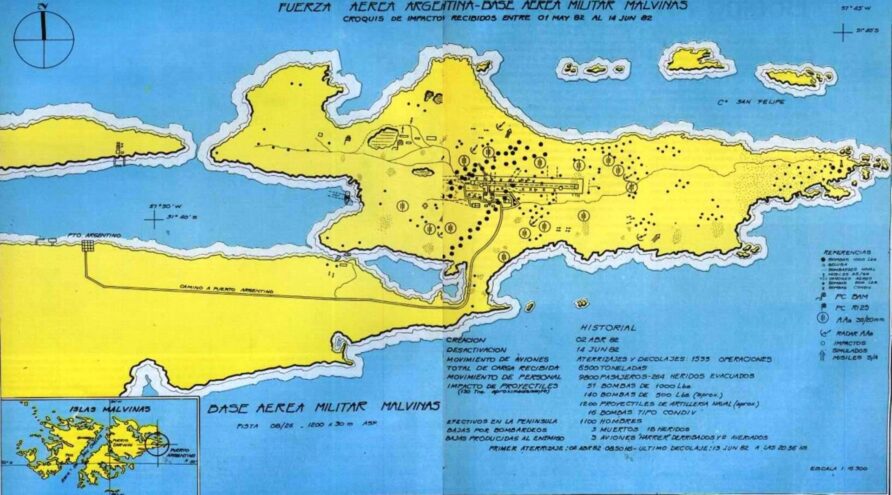

As can be seen from the images above, the airport was also called Base Aérea Militar (BAM) Malvinas, inter service rivalry is common in all armed forces, I think.

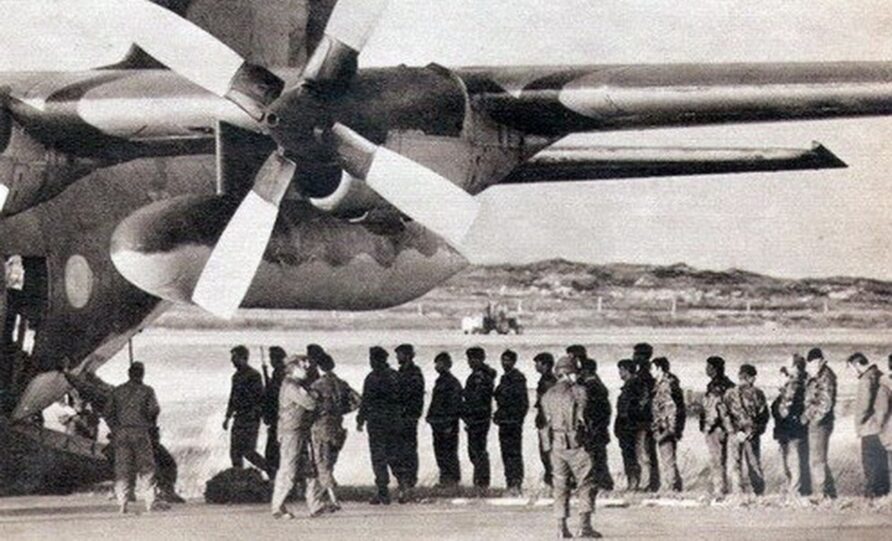

After the surrender of the Royal Marines, they were flown to Montevideo by an Argentine Air Force C130 that had landed at the airport.

Argentine Consolidation and UK Planning

The occupying force then quickly set about reinforcing the Islands from both land and sea, pretty much, with everything they had.

Despite them thinking the British might accept the situation and negotiate, there was always the possibility they would not, and no one fancied a scrap without extensive preparation.

Fuerza Aérea Argentina (FAA) and Aerolíneas Argentinas Fokker F28 Fellowship, Boeing 737, Lockheed Electra and BAC 1-11 aircraft were also used to fly in weapons, vehicles, supplies, and personnel.

FAA C130 Hercules were used for bulky and palletised stores.

The Royal Marines 4 tonner was used for loading and unloading, cheeky buggers.

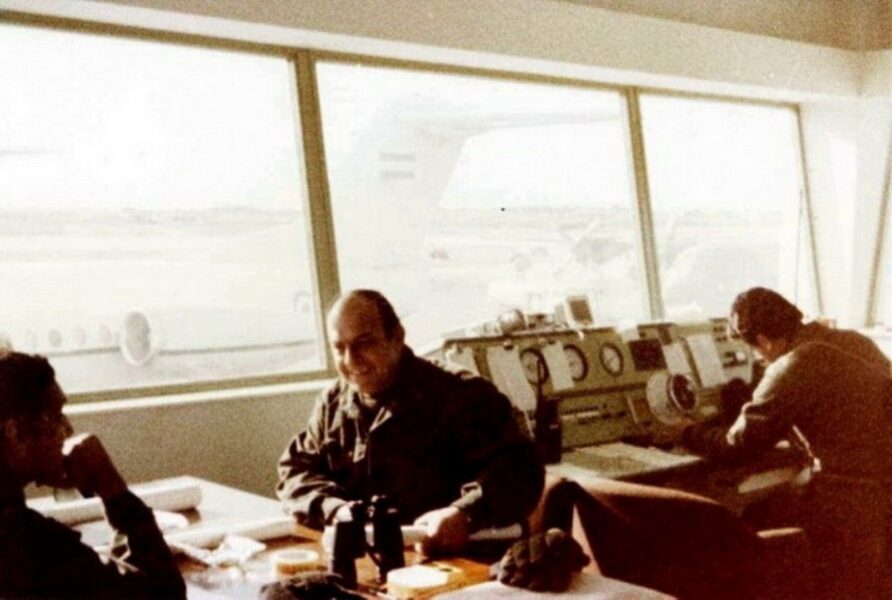

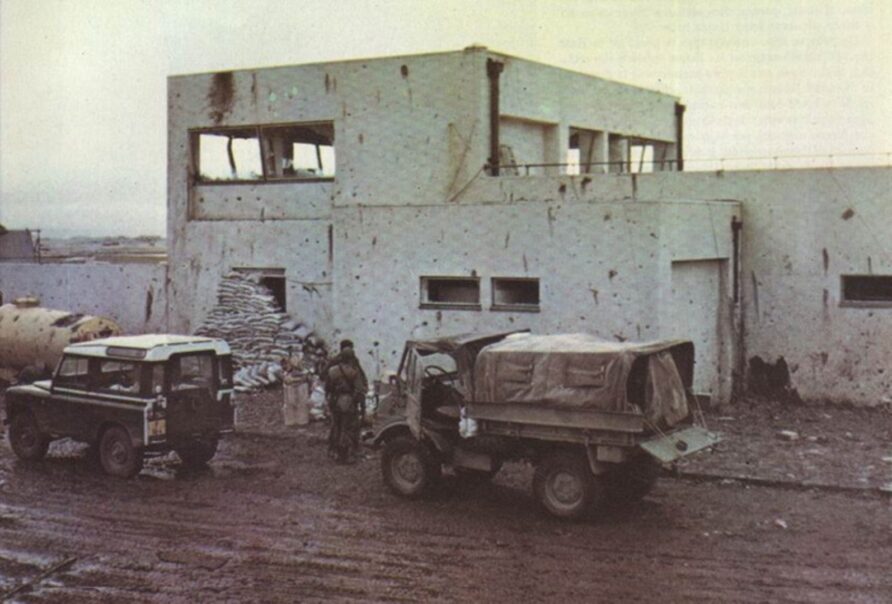

The control tower was a hive of activity (note the intact glass)

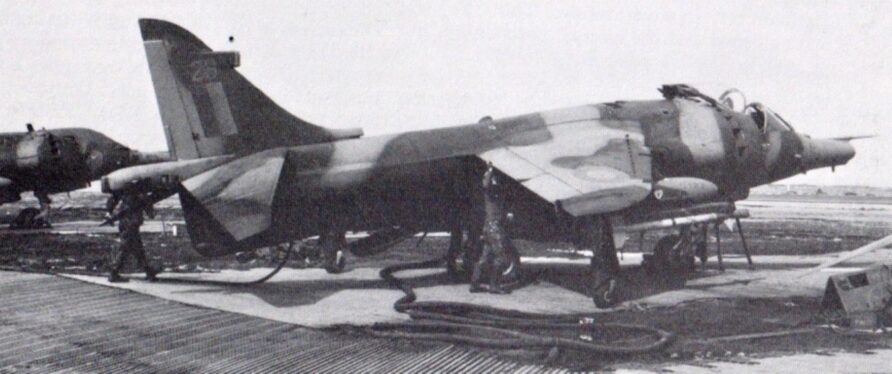

Aermacchi MB339 and Beechcraft T-34C Mentor trainers and light attack aircraft, in addition to the ubiquitous IA 58 Pucara were all based at Stanley.

Chinook’s, Puma’s, A109’s, Skyvans and S-2E Trackers also used ‘La Estación Aeronaval’ during April.

The first to arrive were four Pucaras from Grupo 3, on the 2nd of April.

The S-2E trackers arrived on the 3rd but had left within ten days.

The five S-2 Trackers conducted 528 flying hours over 112 sorties from Stanley.

Two Skyvans (PA-50 and PA-54) and a Puma (PA-13) were used for search and rescue and general transportation tasks.

The FIGAS Islander was also pressed into service, flown by LADE pilots in multiple sorties totalling 30 hours.

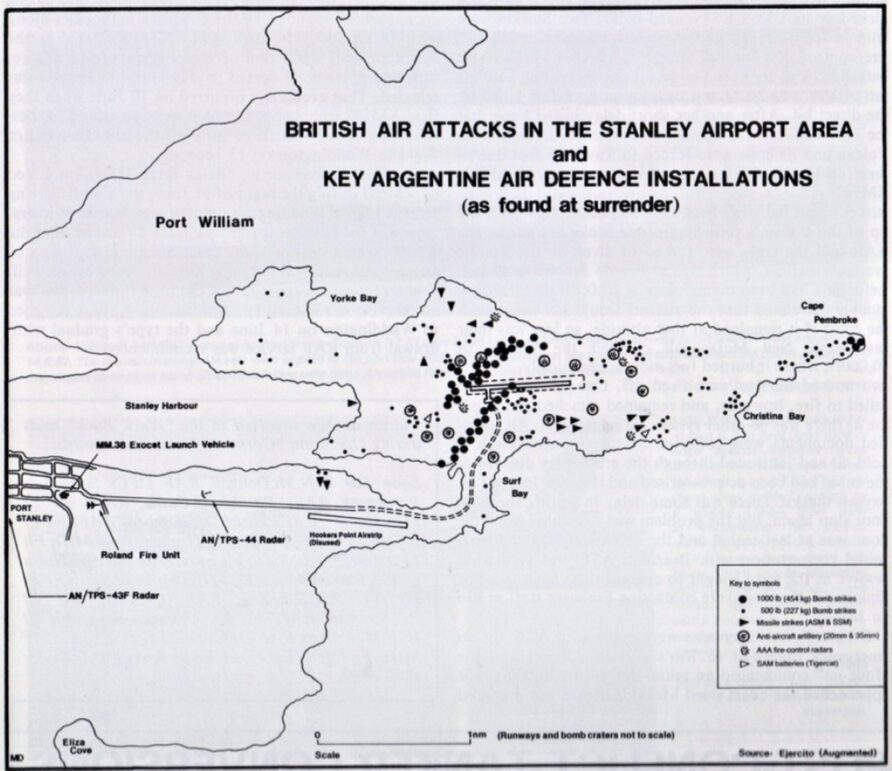

Perhaps the most important early arrival was the FAA’s Westinghouse AN/TPS-43F 3D radar, on the 2nd of April. Although originally intended to enhance local air traffic control, it would go on to be a vital component of the Argentine defence of the islands, and one that, despite the UK’s best efforts, remain operational until surrender.

On the 3rd of April 1982, the UN passed Resolution 502, demanding the withdrawal of Argentine forces, a cessation of hostilities and a political solution.

This came as a surprise to the Argentine leadership, they genuinely thought the UN would support their intervention.

The day after, the Vulcans were being prepared (and by prepared, I mean raiding museums and disposal locations).

The radar was first sited near the airport but then moved to Port Stanley on the 13th of April and disguised among several civilian houses, civilian houses the Argentine forces did, in fact, pay rent for.

A dummy was left in its place.

The FAA used the modern Westinghouse AN/TYP-43F and supporting Ejercitos Cardion AN/TPS-44 radar with a great deal of skill, using its capabilities to extrapolate the location of the aircraft carriers by plotting Harrier movements, for example.

The Cardion AN/TPS-44 was initially deployed to Sapper Hill, but was also later moved into Port Stanley.

Providing local air defence for the airport and surrounding areas were a plethora of systems, including Roland

Tigercat and some different types of radar-guided (Skyguard and Super Fledermaus) and manually aimed medium calibre automatic weapons.

The air defence system was formidable and would also be used to provide advanced warning of ships approaching to attack the area using their guns, specifically, the Cardion radar.

Later in the conflict, they would also be used to support the ground-launched Exocet attacks and counter NGS using the Argentine 155 mm artillery.

The ‘British Military Machine’ was starting to move…

By the 7th of April, there was a realisation in the minds of the Argentine leadership that the world, and more importantly, the UK, was not going to accept the existing state of affairs.

On the 9th of April, US Intelligence reported that Argentina was lengthening the runway at Stanley to accommodate C-130′, A-4 Skyhawks, Mirage/Dagger and Etendard combat aircraft.

This precipitated a crash programme of reinforcement and because of the Maritime Exclusion Zone declared by the UK on the 12th of April and the fear of British submarines meant the bulk of this additional equipment and other stores would have to travel through ‘BAM Malvinas’.

Equipment was taken off ships and broken down for transport via the hard-pressed C-130 force.

By the 10th, the operational tempo of this airlift operation had increased markedly, as had the type of equipment by now streaming into Stanley, radar equipment, anti-aircraft guns, artillery and vehicles, for example.

By the time of the start of combat operations at the beginning of May, the combined Argentine force included 46 aircraft, these would be joined by an additional 12 Pucara and 2 MB339 in May.

They operated from the three main locations of Pebble Island, Stanley and Goose Green, the latter two protected by a formidable integrated air defence system.

Of the 60 aircraft thus deployed, only three would escape destruction or capture.

By the middle of April, RAF Victors and Vulcans had started airborne refuelling practice, and the fleet was well on its way South.

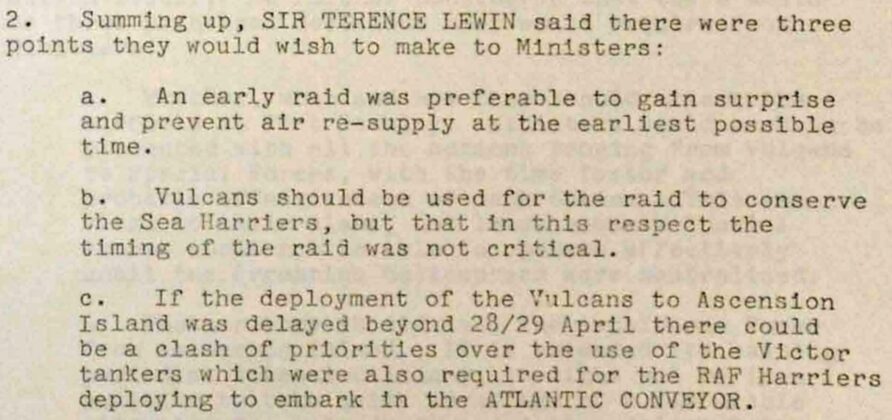

On the 22nd of April, Rear Admiral Woodward requested plans on how the Sea Harriers could be used to interdict Stanley Airport, and this prompted more serious consideration of earlier discussions about the use of the soon-to-be withdrawn Vulcans.

Initial plans had considered a light bomb load to reduce the tanking and fuel requirement, but after tests on Garvie Island, this was revised to the full 21, thousand-pound bombs.

RAF Wideawake at Ascension Island was extremely busy.

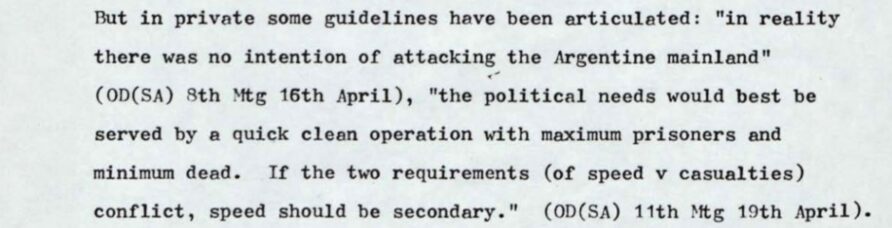

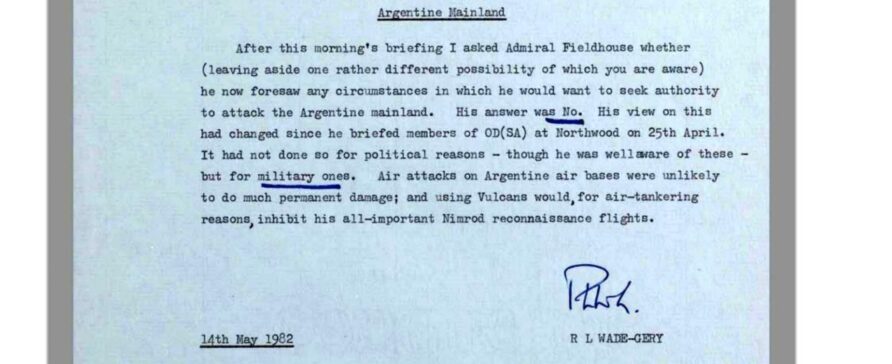

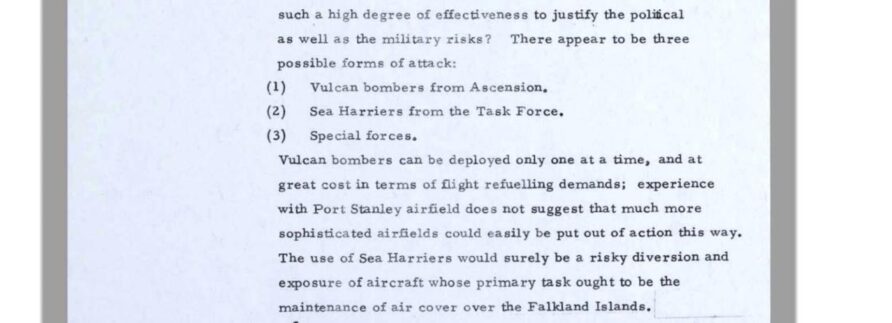

In the following days, there was considerable debate about the merit of the Vulcans, their potential for other tasks, comparisons with the Sea Harrier and the political implications of launching offensive operations off the US base at Ascension.

These debates eventually concluded, Sea Harriers were too important for air defence and not best suited to runway denial were the main decisive points in the debate.

By the end of April, diplomatic efforts had been exhausted, the Argentine forces were facing up to the inevitable, South Georgia had been retaken, and the first Vulcans had arrived at Ascension Island.

If April was a busy but relatively peaceful month for the invaders, May was to be very different indeed.

The Raids on Port Stanley

Argentine forces at Stanley Airport were about to get a wake-up call, XM607 was in its way.

I am not going to dwell on the superb airmanship and improvisation that preceded Black Buck 1 because they are amply covered by many excellent authors such as Roland White with Vulcan 607, Wikipedia is also excellent, and even a casual online search presents many other sources of information.

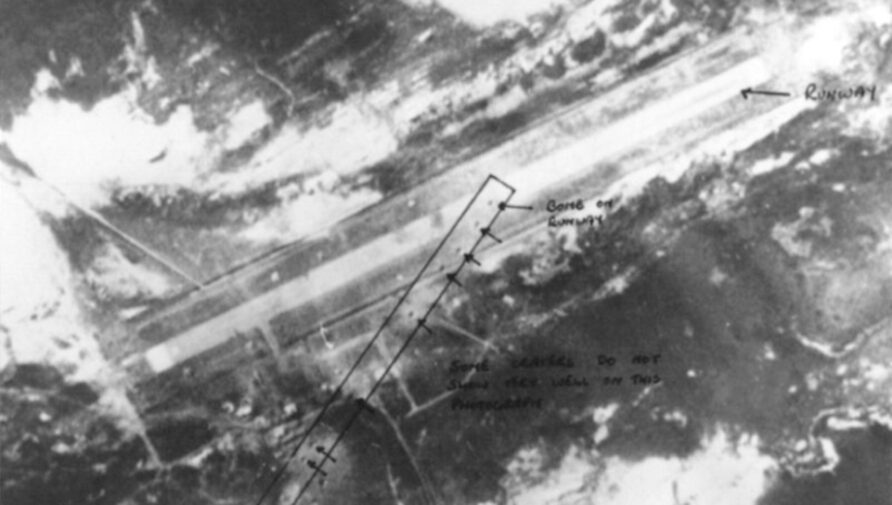

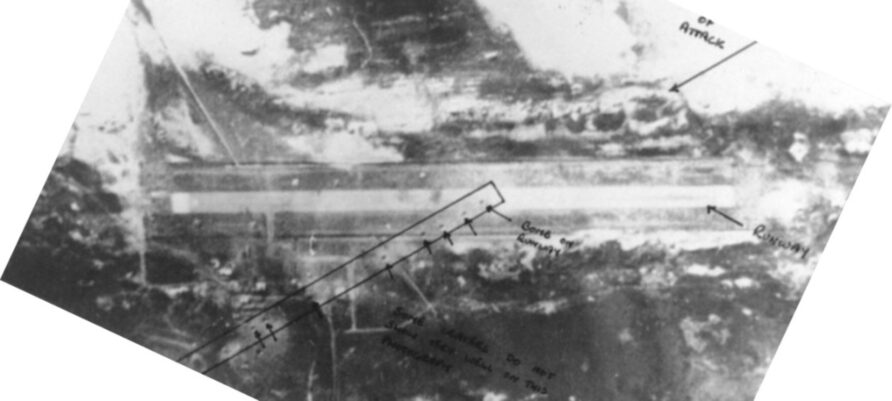

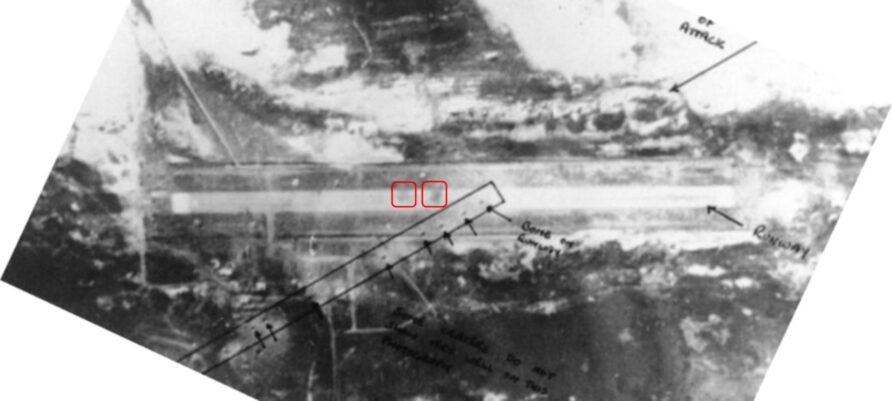

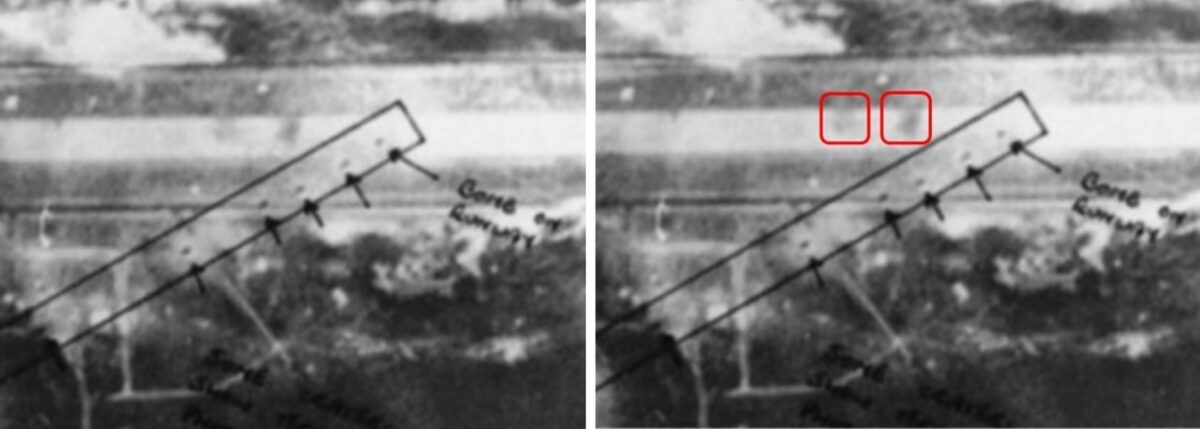

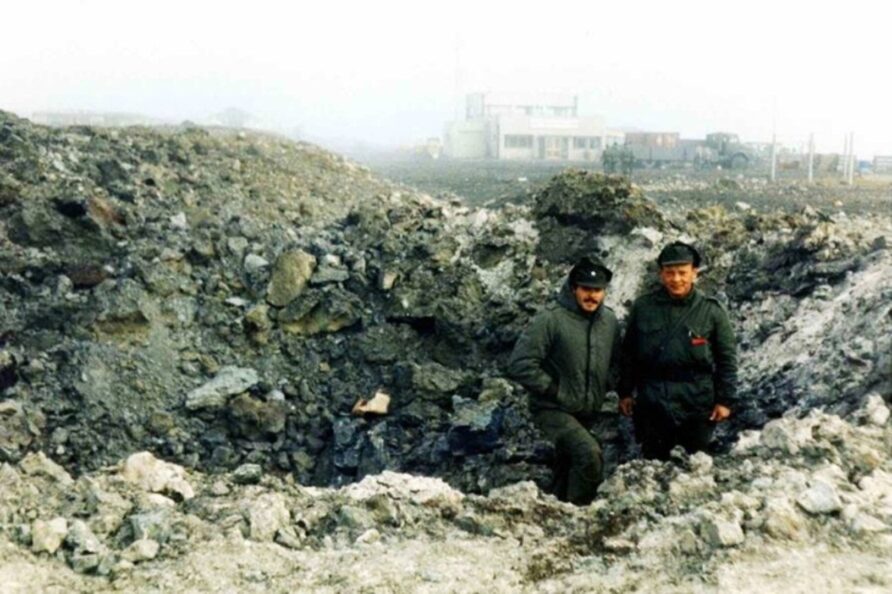

At 4 am, Vulcan XM607 delivered its bomb load of twenty-one, one thousand pound bombs, at an angle of 35 degrees across the runway at Stanley Airport.

It was a bravura feat of arms that took the world, Argentina, and especially, those at Stanley Airport, completely and totally, by surprise.

A follow-up by nine Royal Navy Sea Harriers of 800 Naval Air Squadron with cluster and one thousand pound bombs and naval gunfire from HMS Alacrity, HMS Glamorgan, and HMS Arrow caused further damage.

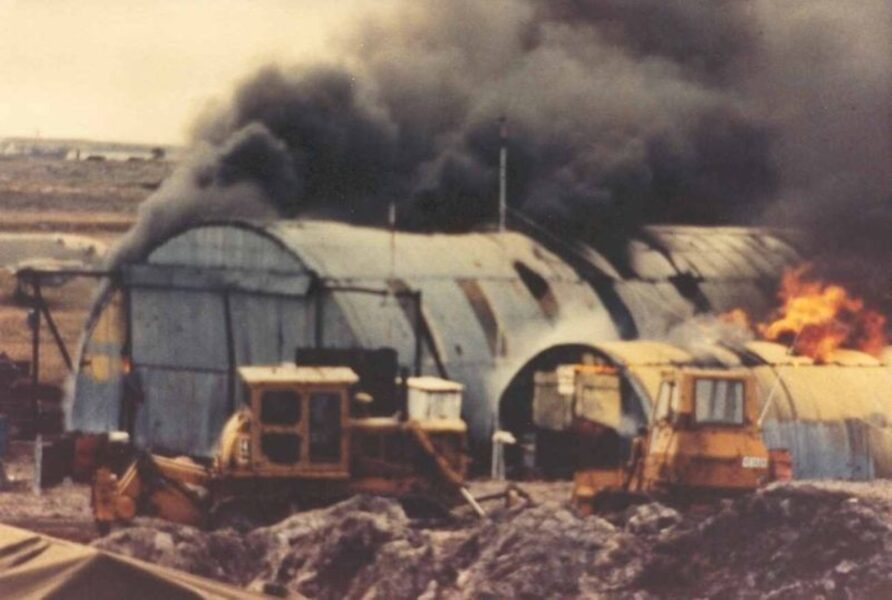

The attacks caused damage to the runway, control tower, fuel supplies and the ‘Quonset’ storage building.

The FIGAS Islander was damaged by one of the Sea Harriers cluster bombs and subsequent attacks.

These attacks also destroyed the three civilian registered Cessna light aircraft operated from Stanley Airport.

Life became a lot grimmer for the invaders.

A Mirage, Dagger, and Canberra were shot down and a similar Sea Harrier/NGS attack was carried out at goose Green, resulting in a destroyed Pucara.

During this engagement, a Grupo 8 Mirage was damaged and attempted an emergency landing at Stanley Airport, it was shot down by Argentine ground forces.

The aftermath of Black Buck I and Harrier raids also caused the hasty departure from Stanley harbour of two Argentine merchant vessels without having fully unloaded their cargo.

The 20,000 tonnes cargo vessel Formosa was later attacked by the Argentine Air Force and sailed all the way back to Argentina with an unexploded bomb in her hull, alongside nearly 4,000 railway sleepers and 200 rails that were to be used for field defences in the hills surrounding Stanley.

The other, the 10,000 tonnes Carcaraña, departed Stanley with 50 tonnes of aviation fuel, all B Company GADA 10s ammunition and vehicles, a multi launcher rocket system and various other stores.

The FIGAS Islander (VP-FAY) was destroyed, its tail severed, during the attacks on the 2nd

Although not at the airport, the FIGAS Beaver float plane was also destroyed during later attacks, the image below is post surrender.

Video, including footage from an Argentine TV camera crew…

The airport control tower was relieved of its glass.

And ventilated.

But, at least, the defending force’s supply of girly magazines survived!

From May 2nd, all resupply flights to Stanley Airport were conducted at a low level and in radio silence and visual blackout.

The inevitable cartoon appeared…

Although not related to the airport, the next day saw the Royal Navy sink General Belgrano with a loss of 368 lives.

On the 3rd, a Skyvan was destroyed at the airport by naval gunfire.

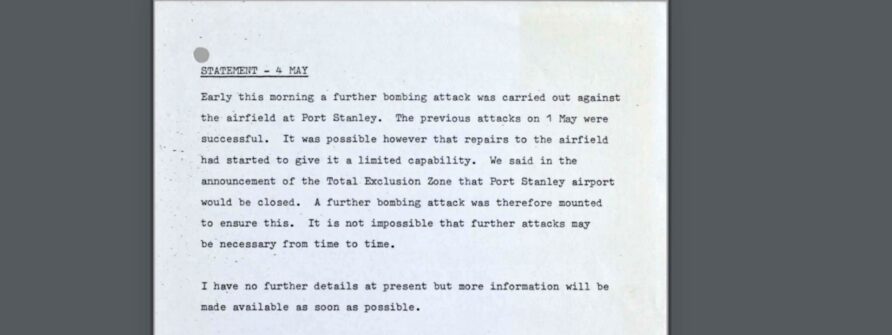

Later that night (early hours of the 4th), Black Buck 2 delivered another load of 21 thousand pounders, the bombs landing to the east of the runway.

A Sea Harrier was lost to enemy ground-based cannon gunfire near Goose Green.

Two Sea Harriers were lost in what is assumed to be a mid-air collision in thick fog on the 6th, and Argentine forces struck HMS Sheffield.

On the same day, another Skyvan was lost in an accident whilst trying to take off.

On May 7th, the Total Exclusion Zone was announced, any Argentine warship or military aircraft found more than 12 nautical miles from the coast would be liable to attack.

During the first couple of weeks of May, despite the intense start to the conflict, diplomatic efforts to bring the conflict to an end would continue.

Positions around the airport were attacked with naval gunfire on the 9th and 10th, and the first blockade running transport mission into Stanley took place on the 15th

A FIGAS Beaver was damaged on the 10th

Sea Harriers attacked the airport on the 15th, 16th, 17th, without significant effect and also on the 17th, a Fokker F-28 flight brought in equipment and evacuated wounded personnel.

Back Buck 3, against the runway at Stanley, was aborted due to severe weather.

On the 18th, the Harrier GR.3’s joined the task force from the Atlantic Conveyor.

OPERATION SUTTON commended on the 21st, the landings as San Carlos. Launching from Stanley Airport, the first attack on the ships in San Carlos water was from an MB339 (4-A-115), piloted by Lt Guillermo Crippa.

For this extremely heroic lone attack, he was awarded Argentina’s highest award for valour.

A damaged Skyhawk attempted an emergency landing at Stanley Airport, but a damaged left undercarriage forced him to eject safely nearby.

The pilot was rescued by an Army UH-1 (AE-424).

On the 23rd, another Sea Harrier attack on Port Stanley Airport was marred by the accidental loss of a Sea Harrier.

The 24th would see the first Sea Harrier and Harrier GR.3a attack on Port Stanley Airport, but fusing issues meant that those that hit the runway failed to detonate.

On the 24th, 4 Harrier GR.3’s and two Sea Harriers launched another attack against Stanley Airport.

The Sea Harriers performed defence suppression by tossing 1,000-pound bombs 45 seconds before the GR.3’s arrived to target the runway with their 1,000-pound retarded bombs.

One Pucara and one helicopter were damaged during the attack, with some minor damage to the runway.

Future attacks against the runway used high angle attacks to achieve desired penetration.

From Wing Commander Peter Squire’s diary;

At midday a mission was tasked as a six aircraft attack on the runway at Port Stanley Airfield. Each pair of GR.3s was led by a Sea Harrier.

The 1(F) pilots flying the mission were Wg Cdr Squire, Sqn Ldr Pook, Sqn Ldr Harris, and Flt Lt Rochfort. The attack was carried out with the GR.3s formatting on Sea Harriers in loose vic formation for a simultaneous release of bombs.

Following the release of his weapons, Sqn Ldr Pook climbed into the airfield overhead to observe ‘fall of shot’. Bombs from the first three aircraft were seen to impact on the West end of the airfield whilst those from the second wave fell approximately 100 yards north of the Eastern threshold.

Whilst in the overhead, Sqn Ldr Pook was locked up by Roland and saw the missile in flight. It peaked at about 15,000ft – some distance below him. He also saw a Tiger Cat launched against the second wave; this too fell short.

Sqn Ldr Harris and Flt Lt Hare later carried out a further similar mission to drop free-fall 1,000lb bombs against Port Stanley Airfield runway from a level delivery at 20,000ft.

The bombs were dropped singly, but aiming for this method of delivery is imprecise, the fall of only 3 bombs being seen and these fell in Yorke Bay.

Harris and Hare both saw AAA and Roland fired during the attacks but their aircraft remained out of range.

Sqn Ldr Harris flew a final late singleton mission to carry out a further medium-level bombing of Port Stanley Airfield runway but owing to the weather, this was changed to 30-degree loft. All 3 bombs fell short of their target

On the same day, laser-guided Paveway II bombs were airdropped to the fleet by RAF C-130 Hercules aircraft and Flt Lt Glover was transported to Argentina aboard a C-130, from Stanley Airport.

On the 25th, another set of sorties was launched against Stanley Airport, two Sea Harriers and four GR.3s.

This time, the bombs were dropped from 20,000 feet (ca. 6 km), none of them hit the runway, some falling into Yorke Bay. The last sortie was forced to release at medium altitude, again, none hit the runway. Roland and Tiger Cat missiles were launched against the attacking aircraft.

It was thought at this time that an arrestor gear system had been deployed to Stanley Airport to support the Super Etendard or Sky Hawk.

The day after, a Fokker F-28 flight to Stanley airport was completed and another sortie against Stanley Airport was attempted.

Three sorties against British forces at Goose Green were launched from Stanley airport throughout the 28th using Pucara and MB339, 3 Pucara and MB339 were lost.

The day after, two flights of Fokker F-28’s and one Electra flew into and out of the airport.

On the 31st of May, following a visual sighting by a Sea Harrier of a ‘swept-wing aircraft, possibly Etendards’, two GR.3’s and Sea Harriers were launched. No such aircraft was found, and it is thought likely they were the Aermacchi.

A single Fokker F-28 flew into and out of Stanley Airport.

Black Buck 5 was executed against radar installations in Port Stanley, to little effect.

On the 1st of June, a C-130 (TC-63) was shot down.

The same day also saw a Sea Harrier from 801 NAS shot down with a Roland missile near Port Stanley. A helicopter and Pucara were launched from Stanley Airport to locate the pilot who had ejected, but were unsuccessful. He was rescued later by a Sea King of 820 NAS.

The 2nd saw an F-28 flight into and out of Stanley Airport and the day after, Black Buck 6, also against mobile radar.

This time, it was more successful and managed to damage the Skyguard radar and kill three personnel.

The day after, two MB339’s were flown back to Argentina from Stanley Airport. Between the 8th and 12th, several F-28 flights were completed. An Argentine C-130 also flew in a number of trailer-mounted Exocet missiles on the 11th and, following some excellent improvisation, were used against HMS Glamorgan on the 12th

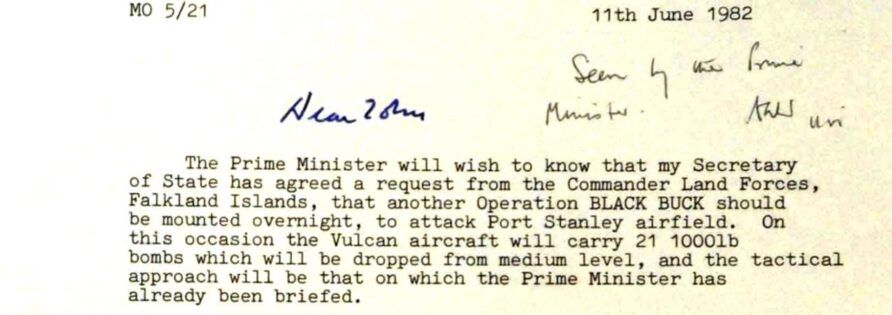

Black Buck 7 was mounted against stores and aircraft at the eastern end of Stanley Airport.

The final supply flight by C-130, carrying 155 mm ammunition, was flown into and out of Stanley Airport, the night before the surrender of the Argentine forces on the 14th.

All three privately owned Cessna light aircraft at Stanley Airport were destroyed during the attacks.

At the cessation of operations, Stanley Airport had suffered three Vulcan strikes, nine multi-aircraft attacks by Sea Harrier/GR.3 and many attacks using naval gunfire.

The total munitions expended included 50 one thousand pound bombs, 135 five hundred pound bombs, many cluster bombs and over 1,000 4.5″ shells from Royal Navy vessels.

The garrison (25th Infantry Regiment and School of Military Aviation Security Company) suffered only three casualties, but there were reportedly significant casualties in other units at the airport.

The airport itself remained operational throughout the conflict, the F-28 force alone managing to transfer over 500 tonnes of supplies and hundreds of personnel.

Between May 1st and June 14th, the C-130(H)’s of the FAA completed 31 flights into Stanley Airport, carrying 514 passengers and 434 tonnes of supplies in addition to evacuating 264 wounded personnel.

Both Hercules and F-28 flights would be carried out at night and time spent on the ground were minimised.

Post Conflict

There is a persistent myth that the Argentine forces were a bunch of frightened, underfed and ill-equipped conscripts with no clue of their business.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Their equipment, often, was superb, in part, much better than that enjoyed by British forces. Defensive positions were well sited and constructed, they had made excellent use of visual deceptions and the radar and ECM equipment were not only extensive but exceptionally well operated as well.

Many were volunteers, thought that right was on their side and fought with great skill, determination, and gallantry. They were not short of most things, there were ample rations, ammunition and equipment, it was just poorly distributed which meant there were many local shortages outside Port Stanley, especially of food.

However, the rift between the officer/SNCO and other ranks was enormous, logistics were inconsistent and several exhibited behaviour that could be reasonably be considered a war crime. At the end of the day, they had no effective campaign plan because, quite simply, they did not expect such a resolute response.

The best soldiers on the planet, sailing 8,000 miles across the open ocean, supported by equally fine air and sea forces, with firm intent, fighting skill, discipline, and centuries of tradition behind them was simply not within their range of expectations.

The occupiers were a spent force.

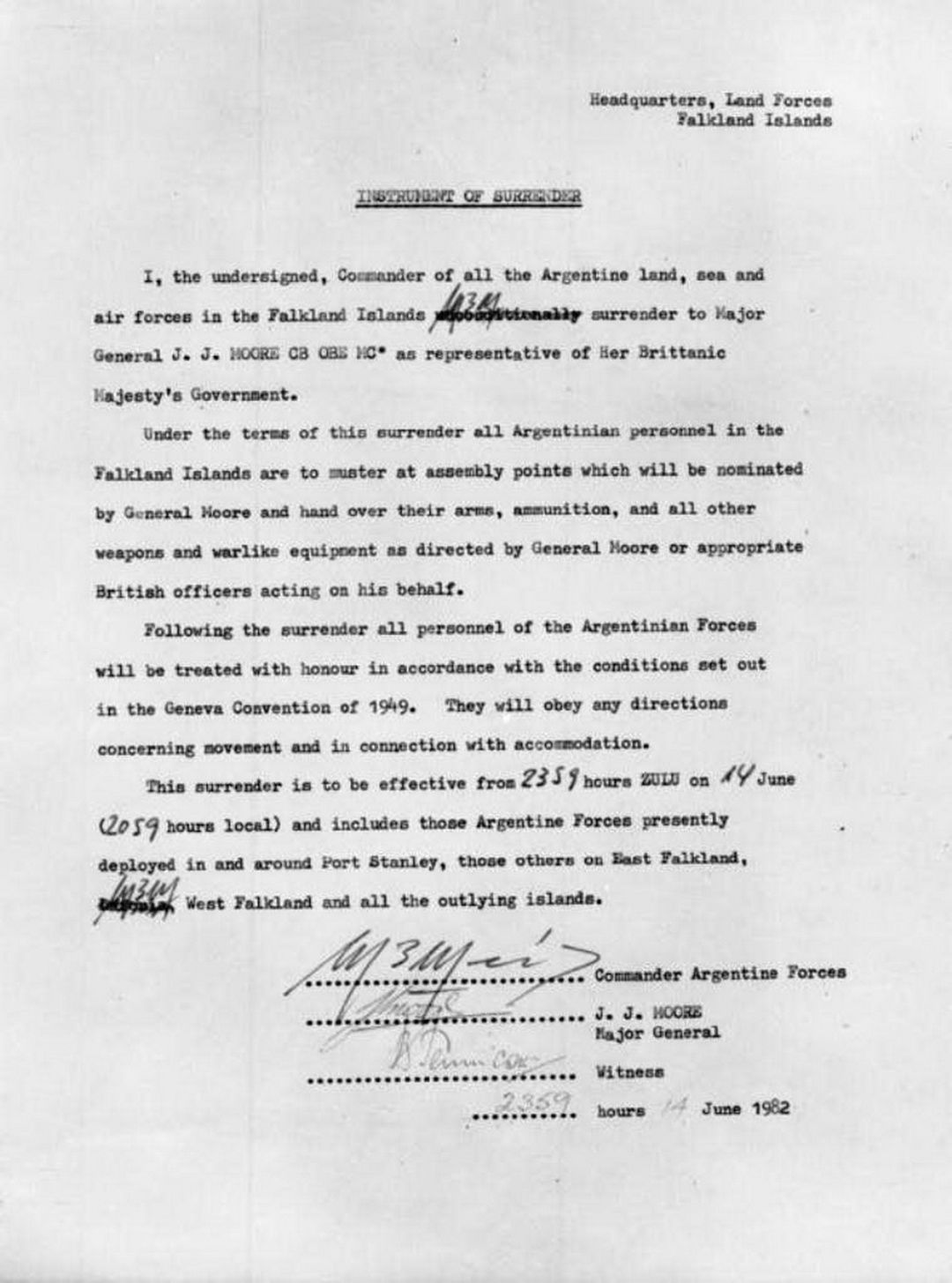

Following the surrender of the Argentine forces, it was now time to consolidate and prevent a rematch.

Although Argentina had accepted the Instrument of Ceasefire they only recognised this locally, there was no wider recognition of the cessation of hostilities so although they were down for the count, the British government recognised that the nature of the unfinished business needed sensible and sturdy consolidation.

Unfortunately, the scale of the other problems facing both the victorious military forces and the civilian inhabitants of the Falkland Islands was immense, there were many priorities, each one of them, number one.

Disposal of the detritus of war, getting the defeated Argentine forces home safe and well, restoring damaged or destroyed utilities, keeping everyone fed and watered, rotating British forces out of the theatre, satisfying the demands of the world’s media and basically getting the islanders back to some semblance of normality all competed with rehabilitating the airport.

That said, commanders were entirely focused on the airport facilities, it might have been competing with other resource demands, but it was generally beating them as well. Unlike the Argentine forces, we recognised the strategic value of air defence from the islands.

For several weeks, there was also a real fear that elements of the Argentine forces might try an armed publicity stunt.

Whilst there might have been some professional respect for the Argentine forces, despite several examples of conduct that fell far short of acceptable, and pity for their plight, much of this evaporated when the extent of damage to Stanley and the degree of booby traps in an area full of civilians became apparent.

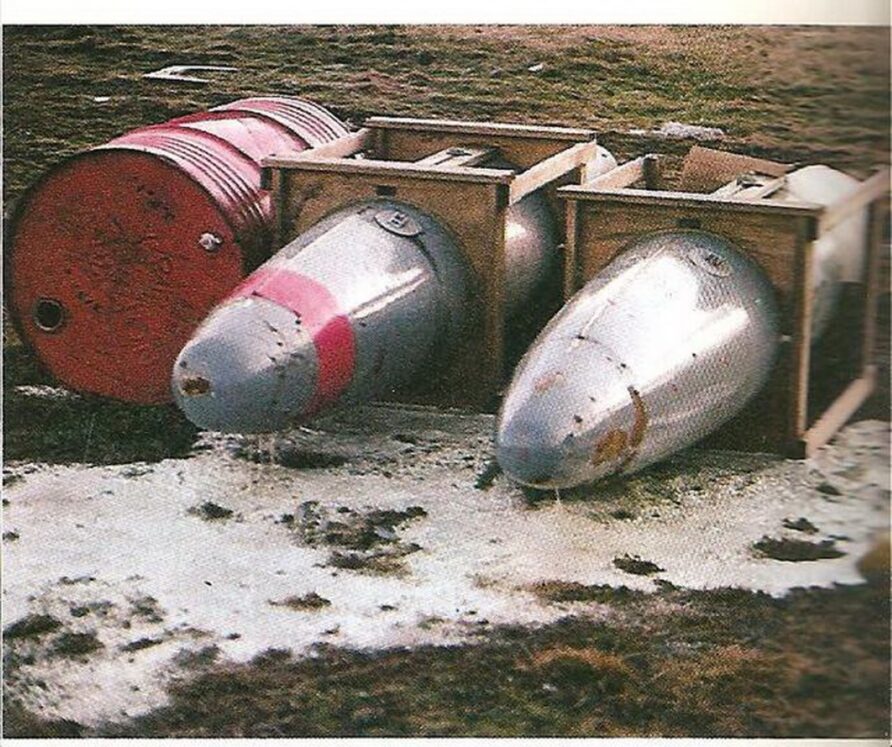

Argentine forces had deliberately set many complex booby traps in the latter stages of the conflict in civilian houses and places of business. These were often linked to attractive items like boots, binoculars, or thermos flasks and many of the discarded munitions were also booby-trapped, some even attached to propane cylinders.

Water supply in Port Stanley was always a problem, Argentine forces even turned all the taps on in houses they occupied and opened fire hydrants. This was in addition to Argentine personnel deliberately treating almost every room in some houses as a latrine.

A vast quantity and variety of mines had been laid, and not just in out of the way locations.

The hazard to civilians (especially children) and service personnel was enormous.

On June 14th, Major Roddy McDonald, the OC of 59 Independent Squadron Royal Engineers, managed to track down the Argentine chief engineer, one Lt. Col Dorago, to assess the scale of the mine problem.

Other personnel from 59 joined in, a warning was broadcast on local radio and through the military chain of command, and fourteen selected Argentine volunteers were utilised to complete the recce.

By the end of the day, the full realisation of the scale of the Argentine mining and booby-trapping efforts had become apparent.

It was staggering.

They simply did not know how many or where mines had been laid, records were incomplete or incorrect, markers had been removed and mines had shifted in peat and deep sand.

The problem was worsened because the Argentine chain of command allowed almost any unit to lay mines, marines, artillery, and all manner of infantry units, not just the professional combat engineers.

After several casualties, the initial clearance effort changed to one of ‘marking only’

The POW volunteer force of Argentine combat engineers expanded, formed a close working relationship with British forces, and received special privileges and pay not enjoyed by other POWs.

A joint guard of honour and bugler were provided for the burials of Argentine soldiers discovered during the clearance operations and in thanks for the rapid Medevac and treatment of an injured Argentine member of the demining team, they paid for and cooked a barbecue for British members of the team and OC of 9 Parachute Squadron RE.

9 PARA left for the UK on the 17th July and were replaced in the mine clearance role by 69 Gurkha Independent Field Squadron RE.

Desalination equipment was lost on the Atlantic Conveyor, as well as tentage for five thousand personnel, exacerbating the problems. 9 Squadron and 61 Field Support Squadron RE managed to get water supplies running after four days, and this was supplemented with water dracones towed into Port Stanley harbour.

In addition, to mines and booby traps, an equally huge problem was that of unexploded munitions of every kind. Everything from small arms ammunition to napalm canisters to anti-aircraft missiles to flares was strewn around the area, half-opened and often poorly accounted for.

‘Dumdum’ small arms ammunition was found in addition to a large stock of SA-7 MANPAD missiles fresh off the plane from Col. Gaddafi.

Grenades, flares, rockets, cannon shells, mortar bombs, small arms ammunition, aircraft bombs, missiles, napalm, and artillery ammunition all needed to be tackled.

Unboxed ammunition was recovered to the UK but anything else was made safe and destroyed by a combined Royal Navy, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Engineers and Royal Air Force team of EOD specialists.

The area of Stanley, a town that normally supported about 800 people, was no home to ten thousand POWs, about five thousand UK military personnel, and, of course, the permanent residents.

And all this was before the problems of the airport had been addressed.

There were three broad objectives for the British Forces concerning air operations.

ONE; Re-establish basic air operations at Stanley Airport such that they could support Harrier and Hercules aircraft. This would allow much of the task force, especially the aircraft carriers, to return to the UK, and replacement forces to arrive quickly.

TWO; Extend and reinforce Stanley Airport to allow the Harriers to depart and be replaced with Phantoms.

THREE; Select a suitable location for a large military airfield that could support all current and future combat and transport aircraft.

Phase One — Establish Operations at Stanley Airport

Stanley Airport, formerly BAM Malvinas, was in an equally poor state as Port Stanley.

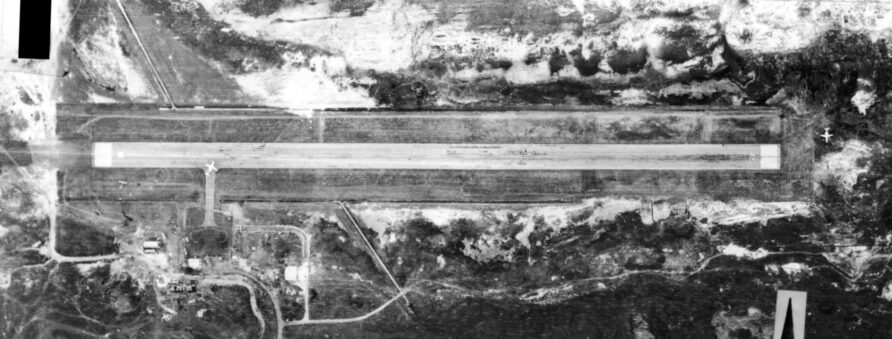

The image below, reportedly taken the day after the surrender, shows Stanley Airport, and the famous dummy crater.

Clearance

The first task was to conduct a survey and make safe any exploded munitions, booby traps and mines, of which there were plenty.

This task would fall to both the Royal Engineers and Royal Air Force EOD teams. No.1 Bomb Disposal Group RAF would play a considerable part in clearing Stanley Airport of unexploded munitions, but that had a difficult start to the campaign. On the 27th of March, they boarded RFA Sir Bedivere with all their vehicles and equipment but when loading had been completed, were ordered off again.

Another four-man team clearing unexploded cluster bomblets from the West Freugh range in Scotland had been killed, and the embarked team were disembarked to complete the task. The team would eventually join the task force by being flown to Ascension Island to catch up with Sir Bedivere.

The team cleared munitions in San Carlos and Goose Green, especially the leaking napalm canisters and mines at Goose Green.

By the time the team had finished its deployment, it had cleared over 900 unexploded bombs, numerous mines and booby traps and tonnes of napalm.

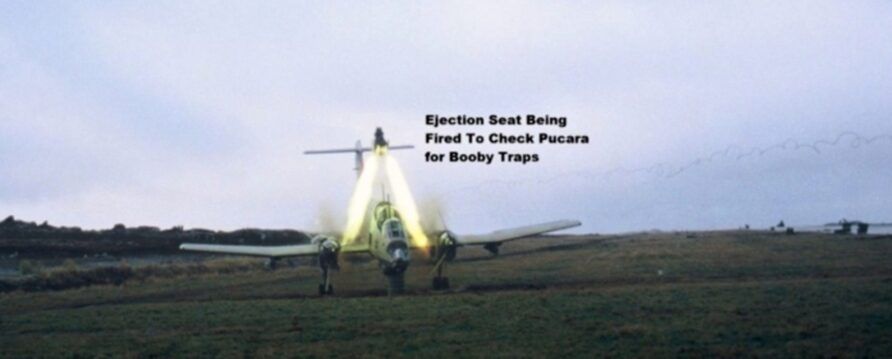

The Argentine aircraft that were left at Stanley Airport were also cleared of booby traps, munitions removed and to prevent accidents by the ever-present ‘trophy hunters’

The ejection seats were removed (firing the ejection seats was also used to initiate booby traps)

Once made safe, aircraft were then moved to an assembly area for eventual disposal

Several PoWs volunteered to remove none explosive debris and sweep the runway after they assumed that such endeavours would earn them a priority ticket home, quite how they came to this belief has never been determined!

Several Exocet missiles were also found, the canisters of which would be used later.

The BAM Malvinas sign was repositioned.

Making Good the Runway

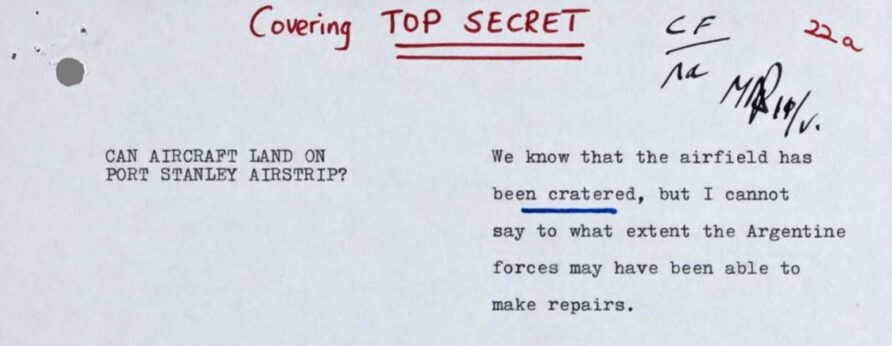

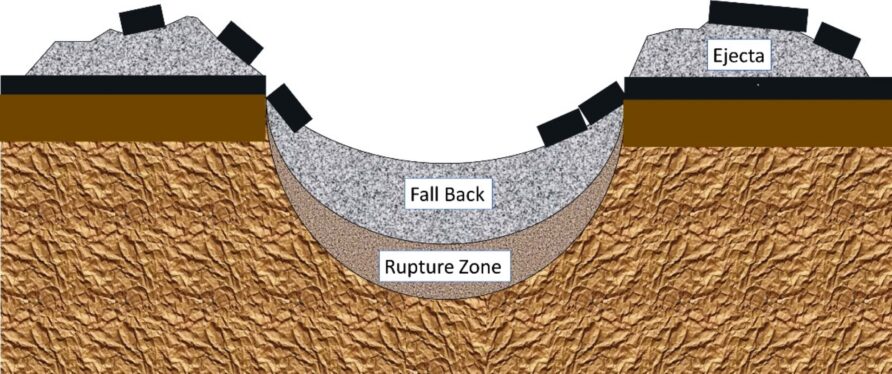

During the conflict, 5 bombs cratered the runway.

The first and deepest was from Black Buck I and the others were much shallower, from retarded bombs dropped by the Sea Harriers/Harrier GR.3a’s.

There were also over 1,000 shallow scabs from rockets, BL 755 bomblets, 4.5” shells and cannon fire.

59 Commando Squadron Royal Engineers (with a troop from 20 Field Squadron) filled in three craters and about 500 of the scabs on the Northern half of the runway, the repairs were made by using magnesium phosphate cement called Bostik 276.

The thousand-pound bomb craters on the runway were backfilled and a quantity of AM-2 repair matting was used to cover them.

It was also discovered that Argentine engineers had used filled oil drums to fill the Vulcan crater, these were removed.

This allowed the runway to be used for planned Hercules flights.

The first RAF Hercules landed on the 24th of June 1982, ten days after the surrender, a magnificent, and generally unrecognised achievement.

Harrier Operations and Airport Development

Using PSA-1 from the Port San Carlos FOB and a quantity of AM-2 matting left at the airport, a short parallel runway, to the north of the main runway, was also created for use by Harriers.

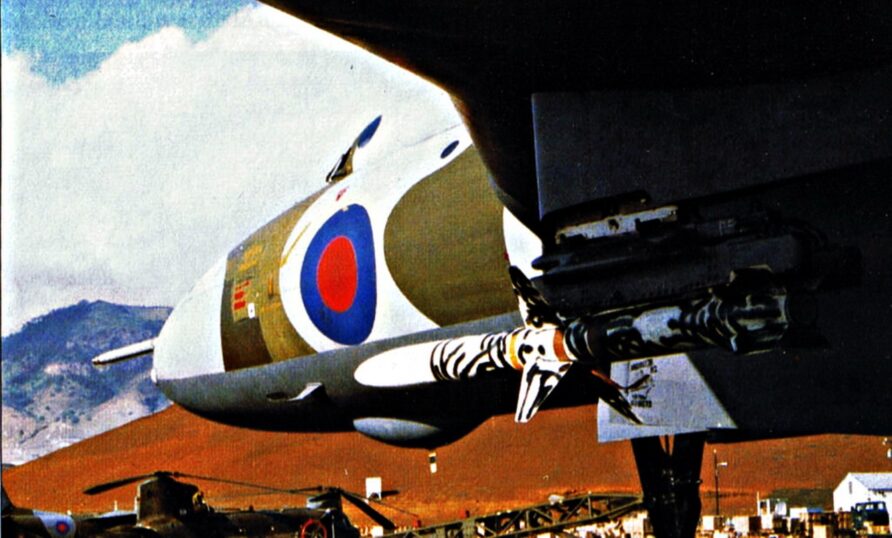

The RAF Harrier GR.3 detachment, armed with Sidewinders, went ashore to Port Stanley Airport on the 4th of July and operated in the air defence role.

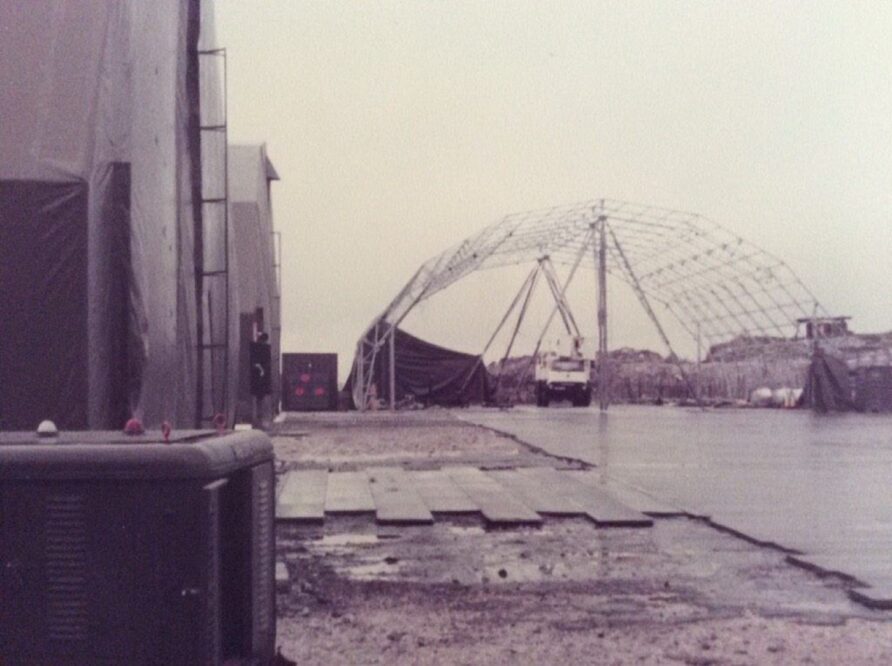

A number of Rubb shelters were installed to provide sheltered maintenance spaces, but the weather was so severe, a number were dislodged and damaged aircraft.

11 Field Squadron Royal Engineers also supported the repair effort and as can be imagined, the tasks were extremely varied. Not widely known is that to create a drainage culvert, the engineers used a pair of empty Exocet missile containers.

In addition, to the runway, the airport support facilities were enhanced greatly, and the sign was changed as well.

The RAF’s 259 Radar Detachment were embarked with their equipment on the STUFT vessel St Edmund on the 20th May 1982. A couple of days after surrender, they came ashore and started work on assembling a mobile radar and TACAN navigation system.

These facilities were then extended and replaced with additional facilities installed at Windy Ridge.

These temporary repairs accommodated 77 Hercules and many hundreds of Harrier sorties before the runway was closed for a more permanent repair and extension on the 15th of August, three weeks after the first Hercules landed.

Phase Two — RAF Stanley

The initial repairs had not repaired the southern half of the runway width and whilst this offered a bare minimum for Hercules and Harrier operations it was not sufficient for anything else.

The runway would need to be properly repaired and extended to support safer Hercules operations and the replacement of Harrier with Phantoms, a much more potent air defence aircraft.

When it became clear that victory would be achieved, the state of the runway at Port Stanley Airport became an issue of serious planning, it would be central to any post surrender defence of the islands. In May 1982, 50 Field Squadron Royal Engineers was given the task of creating an expeditionary airfield at Port Stanley, expectations were, of course, that the Task Force would prevail.

The requirement called for the main runway that would be 6,100 ft (1.86 km) long (from 4,100 ft (1.25 km)), the full width of 150ft (ca. 46 m) and having an LCN of 45 to accommodate fully loaded and fuelled Phantom’s.

In addition to the main runway was a requirement for five Rotary Hydraulic Arrestor Gear (RHAG) sets, sufficient power provision, extensive parking apron, dispersal areas with shelters, roadways, engineering shelters and bulk fuel facilities with a ship to shore pipeline.

Experience with the dispersed air locations supporting the Harrier GR.3 force in Germany was vital, but it also demonstrated to the design team that the UK did not have enough equipment, much of the existing UK expeditionary airfield equipment and stores went down with the Atlantic Conveyor.

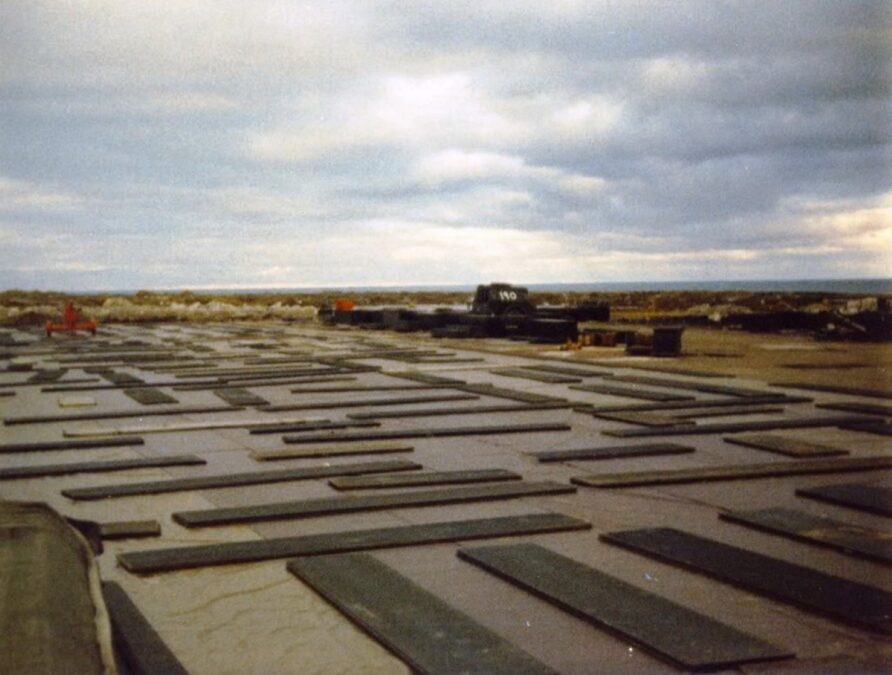

The US AM2 aluminium matting system was the answer to the runway problem.

In Washington, the Air Attaché (Air Vice-Marshal Ron Dick) was despatched to obtain a large quantity of AM2 aluminium matting, arrestor gear and other supplies. The United States was exceptionally cooperative and opened up their war stocks. 50 Field Squadron (Construction) arrived on the 14th of July 1982 and established a project office behind the Stanley Airport control tower.

The 17,000 tonnes MV Strathewe arrived at Port Stanley on the evening of the 17th of July at moorings provided by the MV Wimpey Seahorse. Naval Party 2150 and members of 11 Field Squadron Royal Engineers provided the labour for offloading together with the Composite Port Squadron of the Royal Corps of Transport and was completed on the 5th of August.

The MV Strathewe also carried two 150 tonnes RCL’s (L105 Arromanches and L106 Antwerp) and the heavy stone crushing equipment needed for the runway sub base.

The Cedar Bank was unloaded during the same time frame. Because Port Stanley had no permanent berthing facilities suitable for such large ships, they both had to be offloaded whilst at anchor in Port William Sound.

Making this task more difficult was the weather and the shortage of equipment and suitable slipways.

Enter the RCL and Mexeflote.

The importance of the Mexeflotes and their 17 Port Regiment RCT operators cannot be overstated, without their efforts, the materials required to construct the facilities at the airport would have taken an immeasurable amount of time longer than required.

With a journey time between the ship and B slipway in Port Stanley Harbour of between 30 and 40 minutes, the maximum weights would have to be exploited. AM2 and construction plant is heavy, and even the Mexeflote was seen to struggle on occasions.

Slipway B was the only useable slipway for heavy stores and had to be repaired and reinforced by the sappers before use.

One particularly challenging load was the pair of 45-tonne rock crushers required at the Mary Hill quarry near the airport, the operation had to be carried out at night because they would not fit under the overhead power and telephone wires in Port Stanley, the wires were temporarily lifted as the equipment was very slowly pushed and pulled into place by a recovery vehicle and Combat Engineer Tractor.

In one incident, a pair of Haulmatic earthmovers were lost over the side of a Mexeflote during poor weather. They were eventually recovered, repaired and rechristened as Aquamatics!

A great deal of stone aggregate was needed to provide a sub-base for the AM2 matting. This was obtained from the quarry near the airport at Mary Hill, the source of quartzite for the original runway.

Due to the quantities required for the extension, the quarry needed some additional development and the resultant rock extracted was harder than expected, which resulted in some problems with the crushing equipment as wear rates exceeded the expected.

Blasting operations would often shower the runway with small rocks and dislodge the AM2 matting, which needed clearance and repair.

60 Field Support Squadron, Royal Engineers would eventually provide over 25,000 tonnes of crushed rock for the construction activity.

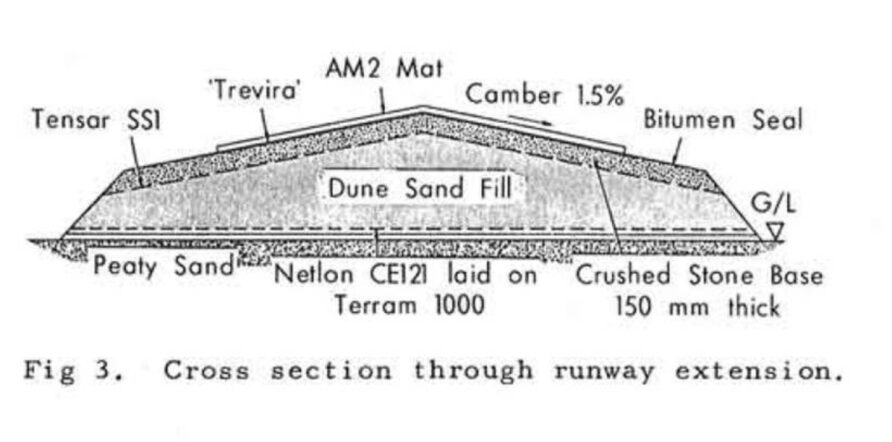

The new runway was to be 2,000 feet (0.61 km) long, at 6,100 feet (1.86 km) and was to have a single uniform layer of AM2, all, obviously, at a single height.

The extension was at the West end of the runway, where Black Buck 2 had dropped its stick of bombs to stop the Argentine forces from extending the runway.

The soil conditions were poor, a mix of peat and sand with a very high water table. AM2 is a 12 or 6 feet (1.83 m) by 2 feet (0.61 m) interlocking aluminium sandwich construction ‘plank’ that fits together to form a single surface. 4,700 tonnes were used at Port Stanley at a cost of £10 million.

The official US description of AM-2 is;

The AM2 is an extruded aluminum mat with a solid top and bottom. The panel is 12 feet long and 2 feet wide requiring a placing area of 24 square feet

The panel is extruded in 6061 alloy aluminum and tempered to the T6 condition. The panels coated with antiskid compound weigh approximately 6.3 pounds per square foot.

The connectors consist of overlap and underlap connections on the ends and hinge joint connections on the sides. The side connectors are integral parts of the basic panel extrusions.

The panels can be placed at the rate of 573 square feet per man hour The AM2 mat qualifies as a medium duty mat based on performance but not on weight.

The AM2 is packaged in bundles containing 11 standard length panels 2 half-length panels and 13 locking bars. In computing material requirements N (equation 17 1) is rounded up to the nearest half panel and a waste factor of 10 percent for new panels and 15 percent for recovered panels is used.

The area to the West of the runway would be used for the extension, but it had a high water table, was peaty and at a different level to the main runway.

New techniques including the use of geotextiles such as the Tensar Stabilisation Grid and Terram textile layers were used to great effect.

The key factor in planning the resurfacing and extension was to minimise disruption to air operations.

As much preparation as possible therefore was carried out before, lest Argentina takes advantage of the gap in air cover from the Harriers, although the cover was available from the Fleet Air Arm.

Despite this cover, speed was of the essence because Hercules flights were being heavily utilised.

Part of the preparations included practising the best techniques, team size and how the installation rate could be best supported by the store’s delivery transport and handling equipment.

The last C130 Hercules departed on the 15th of August, and the runway was closed for refurbishment. The multiple teams swung into action, eight troops of 26 men, Royal Engineers, infantry from the 1st Battalion The Queen’s Own Highlanders and even the odd sailor and airman for good measure.

Two teams were on the go at any one time, working three on nine off shifts.

The wind was a major problem and if a panel’s grip was lost in high winds, the result could be fatal. Competition, intense rivalry and the odd side bet characterised this phase, so much so that it was reported in bad weather, the teams had to be ordered to stop.

Operating conditions were very difficult and in one unfortunate incident a working party of Royal Engineers from 11 Field Squadron and Welsh Guards were injured whilst waiting to cross the runway, some severely, when a Sidewinder missile was accidentally fired from a Harrier.

A bulk fuel facility was established near the runway and a pipeline laid across the mined terrain to the beach at Yorke Point. This pipeline was apparently earmarked for disposal but had been squirrelled away by an enterprising QM at Long Marston and sent south.

A floating pipeline was then used to connect the main pipeline to a beached fuel-filled dracone.

When empty, the dracone would be towed out, by a Royal Corps of Transport workboat, to a waiting tanker anchored in Port William and refilled.

The three, later five, Rotary Hydraulic Arrestor Gear (RHAG) required concrete foundations but when complete, could dissipate 65mJ of energy to allow a tail hook equipped 23-tonne aircraft landing at 130 knots to come to a complete stop in 350ft (ca. 107 m).

The RAF Hercules would still fly in this period, instead of landing, they would airdrop supplies at Seal Point and even used the snatch method to pick up sacks of outbound mail.

From the Lyneham Village website;

In this period, the Hercules maintained a regular service to airdrop supplies and also to collect mail, using the snatch method developed at short notice during June/July at the Joint Air Transport Establishment based at Brize Norton.

The equipment in the aircraft comprises a grappling hook trailed on 150 ft (ca. 46 m) of nylon rope, and a pair of powered winches used to wind the rope, hook and mail bag back onto the aircraft after the snatch.

Ground equipment comprises two poles 22 ft (ca. 7 m) tall and 50 ft (ca. 15 m) apart, with a loop of nylon rope slung between and the mail bag (up to 100 lb (ca. 45 kg)/45 kg in weight) attached to this loop by another 150 ft (ca. 46 m) length of rope.

The poles are set up so that the rope between is at right angles to the wind, and DZ (Drop Zone) markers are set up at 300 ft (ca. 91 m) and 600 ft (0.18 km) distance on the approach. Trailing the grappling hook, the Hercules flies at 50 ft (ca. 15 m) above ground level to snatch the bag.

About 30 snatches were made in this way before sufficient length of runway was again available at Port Stanley.

Two days ahead of the scheduled completion date, the complete runway was ready on the 27th of August. The first Hercules landing on the new billiard table smooth surface was completed the day after.

Upon completion of the runway, the Royal Engineers proudly erected a suitably painted sign (signwriting being an RE trade) proudly announcing the opening of Holdfast Airport.

It wouldn’t last long, of course, after a Vulcan sized sense of humour failure, the RAF removed it and renamed the place RAF Stanley!

The Sappers couldn’t moan too much, though, given their original sign was too large.

As can be seen in the image below (with kind permission of Sqn Ldr Pete Kettell RAF Ret’d), when they pushed the last section in, the first section was pushed out.

Measure twice, paint once.

Members of the RAF movement squadron arrived and painted the tower green, with 3” brushes.

And an appropriately sized sign fitted.

The control cabin on the roof above the sign was eventually recovered to the UK and used at Priština Airport by the RAF in 1999.

Rubb and spandrel type hangars, together will all manner of engineering and logistics support facilities, were installed and improved.

Helicopters (including Bristow SAR) and Harrier GR.3’s continued to operate from the new facilities

New additions arriving air-freight.

Helicopters (including Bristow SAR) and Harrier GR.3’s continued to operate from the new facilities.

With the completion of the extended runway at RAF Stanley, the first Phantom from 29 Squadron located at Ascension arrived on the 17th of October., shown below.

Seven other Phantoms were to follow in short order although, in the interim, the Harriers would soldier on.

These were replaced later by 23 Squadron. 18 Squadron, who had been operating Chinooks since the conflict, continued to use RAF Stanley.

The image below shows the Rotary Hydraulic Arrestor GEar (RHAG) in action.

The AM2 can be clearly seen in these images

Elsewhere, 29 Squadron, with three F4 Phantom FGR2’s, took over the Quick Reaction Alert task at Ascension Island from the Harriers of 1 Squadron on the 25th of May.

Hercules refuelling tankers would also have to play a significant role in operations at RAF Stanley, as did Nimrods and, reportedly, Buccaneer aircraft.

With repeated use, AM-2 has a tendency to ‘walk’ down a runway and so every six weeks, OP BENDER (honestly) would be carried out to pull the complete runway back into position using chains and heavy vehicles.

This at first took 36 hours to complete but was reduced to 12 hours by the end of RAF Stanley’s use.

Quarrying continued and would present a hazard to flight operations, but this was carefully managed.

Joining the Phantoms at RAF Stanley in the Falklands Islands Air Defence Ground Environment (FIADGE) were two radar stations, first on Mount Kent, then Byron Heights and Mount Alice, where they remain to this day.

Each site required 700 ISO containers of equipment and materials to be flown there by Chinook.

RAF Stanley even had a famous visitor, or two.

Margaret Thatcher visited the airport in January 1983, transported there in an RAF C130 Hercules that had been fitted with a VIP pod. The 24×9×8 ft (2.44 m) pod contained four ex VC-10 seats, bunks, and washroom facilities.

The Prime Minister’s Hercules took off from Ascension Island with an accompanying Hercules, at 1,300 nm the Prime Minister’s rendezvoused for refuelling with a Victor tanker (itself having been refuelled a 1,000 nm south of Ascension Island), at 1,800 nm the Victor refuelled the Hercules Tanker.

Finally, at 2,600 nm, the Hercules tanker refuelled the Prime Minister’s Hercules and returned to Ascension Island.

The return flight was to use the same aircraft but unfortunately, it developed problems at RAF Stanley, forcing the ‘Iron Lady’ to travel back on a standard Hercules, without the comfort pod.

Phase Three — RAF Mount Pleasant and Beyond

Plans were made for a large, strategic airbase on the Falkland Islands in 1983

In June 1983, Michael Heseltine MP made the following statement to the House of Commons

With permission, Mr. Speaker, I will make a statement about the Government’s decision on the construction of a new strategic airfield in the Falkland Island.

The Government believe that the defence of the Falkland Islands, the support of the garrison and its reinforcement in emergency depend on permanent and improved airfield facilities; and the Government welcome the recent useful report of the Defence Committee which supports this view.

The present airfield at RAF Stanley is temporary and operations are restricted by the length and strength of its single runway. Therefore, we have examined the alternatives of improving RAF Stanley or of building a new aifrield on a clear site at Mount Pleasant, which is between Stanley and Darwin.

We have now decided that the right course is to build at Mount Pleasant. This is less expensive, even allowing for the cost of a road between Mount Pleasant and Stanley, and is much less likely to involve unforeseen delays and interruptions to the construction work. Most important, the use of RAF Stanley by the garrison will not be restricted while the new airfield is being built.

The new airfield will be able to operate wide-bodied aircraft, civil as well as military. This will enable us to make welcome savings in the running costs of supporting the garrison; it will greatly reduce the amount of time required to reinforce the garrison if need be; and it will give a powerful boost to the economy and infrastructure of the islands.

Tenders have been received from three consortia of British civil engineering contractors and a contract for the construction of Mount Pleasant airfield will be placed very shortly by the PSA with the consortium of Mowlem-LaingAmey Roadstone Construction. The value of the work to be executed under this contract, together with the costs of sub-contracts and shipping, is approximately £190 million. To this will be added the cost of the Stanley to Mount Pleasant road and a separate contract to install Government-furnished communication and navigation aids, making a total of about £215 million.

This order of cost was allowed for in the additional provision for Falklands expenditure included in the Defence budget and will not therefore add to planned public expenditure or necessitate offsetting reductions in defence expenditure elsewhere. The labour force will be recruited in this country. Work on the site will begin this autumn—the Falklands spring— and the new runway should be usable from April 1985. The whole airfield complex, including all the necessary facilities, will be complete by about February 1986.

I believe that this statement will be generally welcome, both in Parliament and in the Falklands, and will be seen as another practical sign of our determination to ensure the security of the islands.

In the same year, the Falkland Islands Government Aviation Service (FIGAS) took delivery of two new BN Islanders, replacing those destroyed during the conflict.

Building such a large airfield, with all modern facilities, in the harsh and remote conditions of the Falkland Islands was an incredible feat of civil engineering and project management.

Everything had to be transported in.

The main runway and essential support facilities were completed by April 1985, with additional facilities completed in the following years.

Stanley Airport was returned to civilian use soon after and the AM2 runway matting removed.

FIGAS has since taken delivery of a number of additional BN Islanders.

The current Aerodrome Plan can be found at this link and there are a number of ‘camp airstrips’ on both East and West Falkland, an example below at Fox Bay.

The Airport today, with that all-important sign.

FIGAS continues to operate a fleet of Britten Norman Islanders, servicing remote airstrips and the main airport at Stanley.

Click here for a fantastic aerial view of the airport, you can still see some craters.

A Short Note…

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Back to the Article…

Observations and Discussion

Airpower was going to be fundamental to success or failure in the 1982 Falkland Islands conflict, and the Black Buck raids by RAF Vulcan’s against Stanley Airport and the occupying Argentine force were indicative of the importance of denying occupying forces a functional runway.

The Black Buck Vulcan missions tend to evoke strong opinions, and discussion can often descend into a childish and narrow argument.

There are numerous books and online resources that look at the actual missions, and that they demonstrated superb airmanship and improvisation is not in doubt, but not much that examines their actual effectiveness.

So I want to present what, I hope, is a fair-minded and reasonable look at their effectiveness, and some claims and counter-claims made in numerous books, magazines, blogs, and forums.

I intend to do this by looking at them from a ground perspective, engineering, and logistics.

Before starting, I want to make clear a few things.

I am not a professional historian, aviation civil engineer or photographic analyst, have spoken to no one who was there, was not there myself and only had access to open-source information when writing. This means that anything that follows this sentence must be viewed in that context.

This is merely one opinion of many, not authoritative or final. Read my ‘working out’ and agree or disagree with the conclusions, but please do not lose sight of those limitations.

That they were superb examples of airmanship, skill, adaptability, and determination is not in dispute, discussing their effectiveness does not detract in any way whatsoever from that.

Discussion tends to narrow down into single subjects, but in viewing the effectiveness of the raids, one has to look at the bigger strategic and political picture. Information we know today may well not have been known then, there was no internet or immediate communications, planners and other personnel had to work on limited information at a breakneck pace, let’s not forget, it was all over in ten weeks.

I also think most commentary tends to a narrow focus on events immediately before and after Black Buck, ignoring what came before and after the conflict.

Both these aspects are neglected, but they are all related to any analysis.

So, with that in mind, and as if the Internet doesn’t have enough Black Buck commentary, here we go, a few thoughts on that, and what went before…

Before the Invasion

The belligerence and attitude of the Argentine government were well known, so when the contract for the construction of Stanley Airport was let to Johnson Construction in 1973, it would not have been totally outrageous to ensure that pre-built demolition chambers were installed at key locations on the runway.

The concept of pre-built demolition chambers in major infrastructure projects was, at the time, relatively common.

The cost of creating such chambers during the build phase would have been negligible.

These would have allowed the rapid denial of the runway using simple explosives, well, within the non-specialist skill-sets of Naval Party 8901 (Royal Marines).

However, given that LADE operated services from Stanley Airport, this might not have been a politically acceptable solution, but there were other alternatives available.

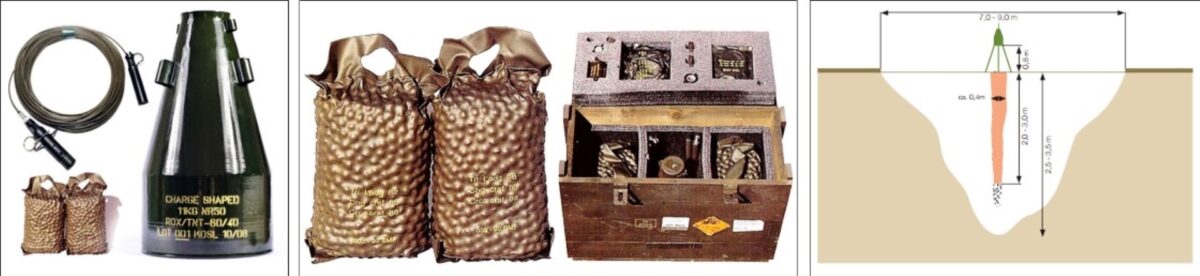

One such alternative to a pre-built demolition chamber is the Rapid Cratering Kit, in service at the time, as they are today.

Although the modern version is shown below, the principle is the same. A shaped charge (beehive) is used to, effectively, drill a hole in the asphalt or concrete runway surface. The cavity (or camouflet) is filled with a larger charge of explosives and when detonated, the resultant crater is much larger than simply placing the explosives on the surface.

They are very effective and quick to deploy.

Typically, the explosively drilled hole extends between two and three metres and with a charge of 30 kg, the resultant crater can be up to 8m wide and 3.5m deep. The total packed weight is approximately 60 kg.

If NP8901 had, among their strength, a section from 59 Commando Squadron Royal Engineers, they may well have had some engineer stores, including RCK’s.

There is no doubt they would have had the skills and time to use them on the runway, possibly on pre-surveyed and marked locations on the runway.

Placed on the centre-line and at regular intervals down it, repairs would be difficult and the ‘undermining’ effect would have created significant structural weakness simultaneously on both sides of the runway.

The Official History of the Falklands Campaign records some information about runway denial;

On the other hand, having been given no advice other than to dispose of his meagre forces and do what he could, Hunt might have appreciated a bit more information.

No guidance was given on how the Argentine forces might arrive, including their likely use of amphibious personnel carriers, though this might have helped when choosing which beach to defend.

The only suggestion received was to crater the runway, but there was no time to do this properly: it would have involved drilling holes to insert dynamite. All that was possible was to attempt to block the runway with vehicles.