Watchkeeper is a certified Uncrewed Aircraft System (UAS) that provides the Army’s Land Tactical Deep Find capability.

It is equipped with a configurable intelligence and reconnaissance payload, supporting Corps and Divisional understanding and the ability to enable long-range targeting of enemy activity, during the day and at night.

The value of aerial reconnaissance…

I hope none of you gentlemen is so foolish as to think aeroplanes will be usefully employed for reconnaissance purposes in war. There is only one way for commanders to get information by reconnaissance, by cavalry

General Douglas Haig, 1914.

Before Watchkeeper

The British Army (and Royal Artillery) has a long track record with uncrewed vehicles, and championed their use before they were trendy.

The first proper UAV in UK service (accepting the 1939 Queen Bee target system) was the MQM57-Falconer bought into service by 94 Locating Regiment, Royal Artillery in 1964.

The Regiment comprised three Batteries, with 57 (Bhurtpore) being the one to operate the Midge.

There is a very brief glimpse of a Falconer in this British Pathé video clip, 1:50 minutes in. The Falconer was never called that in UK service but instead, SD-1, an abbreviation of the US designation, ISD-1.

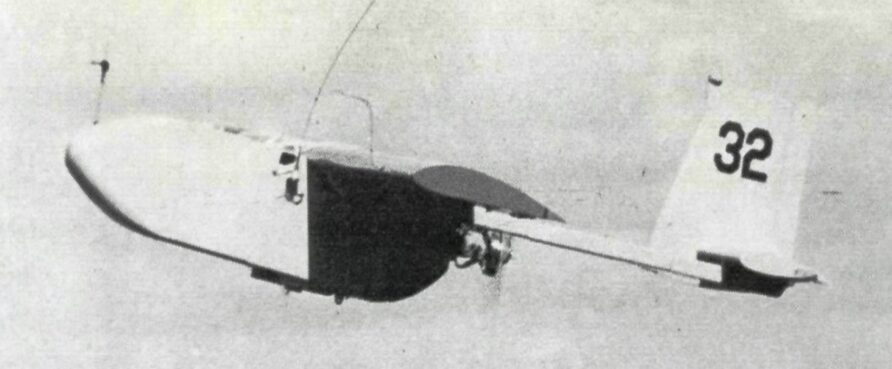

The Canadair Midge 501 replaced the Falconer, a UK version of the Canadair CL89.

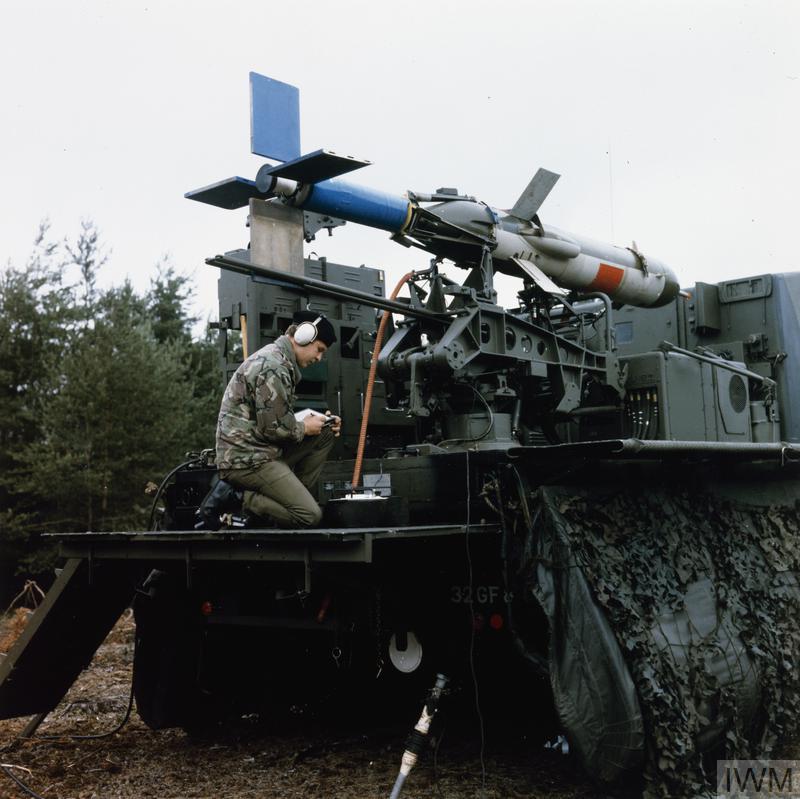

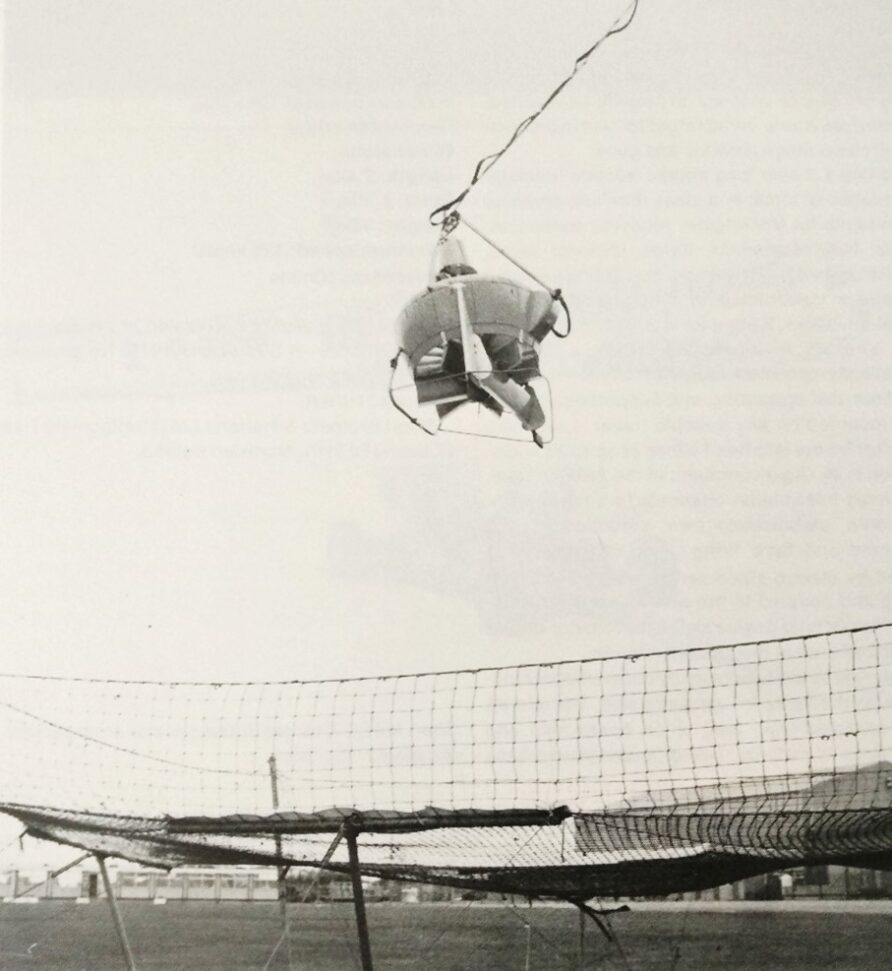

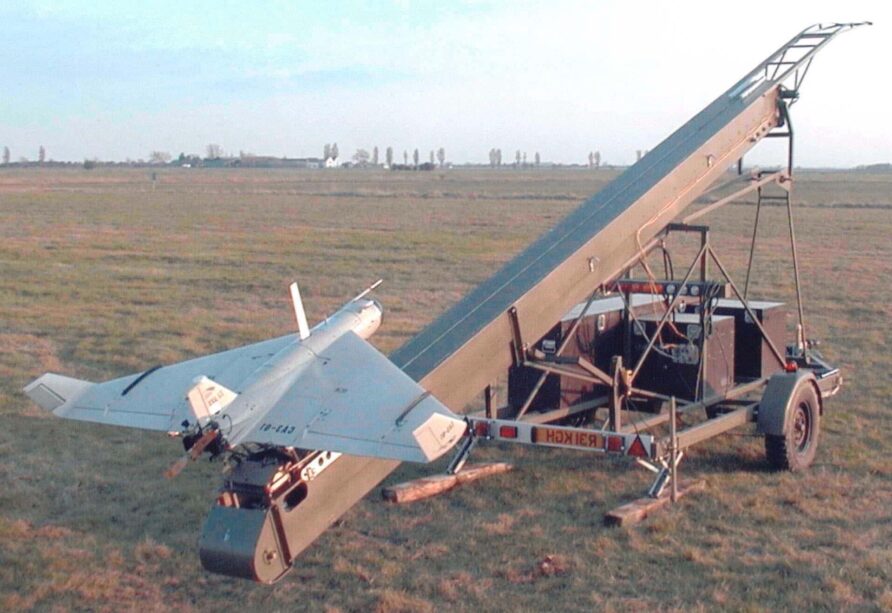

The Midge was more or less a recoverable missile that flew a pre-planned route and was fitted with an IR line scan and a traditional optical camera. Launched from a truck-mounted rail and recovered by a parachute, the Midge was primarily used as a divisional resource to locate enemy artillery so they could be destroyed in a proper big gun artillery duel!

Midge came into service in 1971, again with 94 Locating Regiment, Royal Artillery.

The same cameras from the Midges were also mounted on Army Air Corps De Havilland Beavers.

The video below shows the CL-289 or AN/USD 502, an improved version of the CL-89.

The year after Midge came into service, Westland Helicopters began concept development work on a small unmanned rotary craft. By 1975, this initial concept and wind tunnel work had progressed to the development of an aerial test bed called Mote.

Also in development during the same period were the Shorts Skyspy

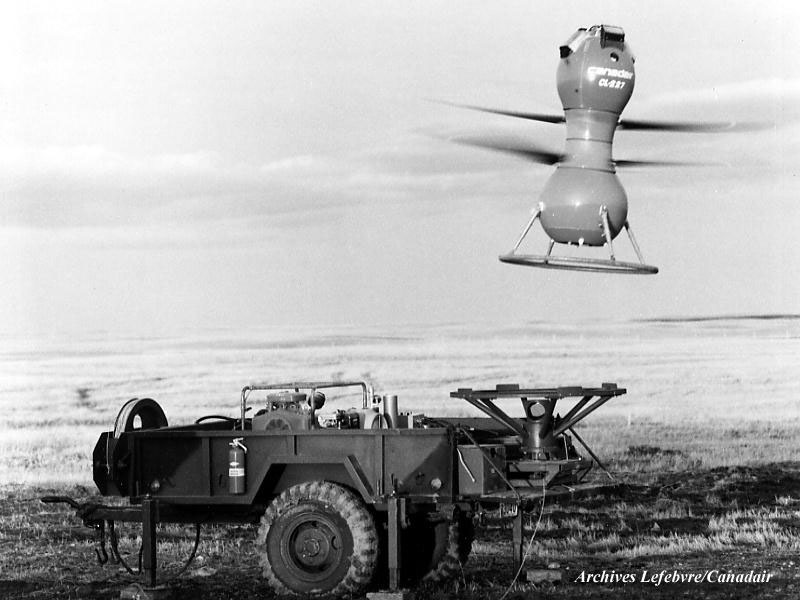

…and Canadair CL-227, all small, uncrewed and rotary.

After Mote, Westland Helicopters developed the Wisp.

All were considered by the Army but eventually, Westland was chosen to develop a larger version of the Wisp, called Wideye, as part of the Supervisor Battlefield Surveillance Programme.

Powered by two 18 hp engines, driving contra-rotating blades, its payload was a Marconi Aviation stabilised camera with a radio data link, able to provide imagery to a range of 50 km.

The selection of Wisp/Wideye was considered a lower risk option, but the ducted fan Skyspy from Shorts clearly showed potential for much greater resistance to landing damage than an open rotor system, and its radar signature was also considerably lower.

Supervisor and Wideye were intended to come into service in the early eighties, but in 1980, the MoD cancelled the Supervisor Programme after spending £12m on the feasibility studies. It was reported that the MoD decided to opt for a lower risk solution.

After cancelling Supervisor, the MoD went back to the drawing board and started concept work for a Midge replacement under GST 3846, again, amusingly called Phoenix.

The system was supposedly named Phoenix because it rose from the ashes of the Medium Range Unmanned Aerial Surveillance and Target Acquisition System (MRUASTAS) programme.

This was to be an unmanned rotary platform from Westland’s described above.

In 1967, the Westland Helicopter future projects team developed the concept of an unmanned rotorcraft fitted with an electro‐optic sensor to provide the function of battlefield surveillance and target acquisition. The concept envisaged deliberate penetration of hostile airspace with a small “semi‐ disposable” aircraft as an alternative to manned systems that were seen as increasingly vulnerable

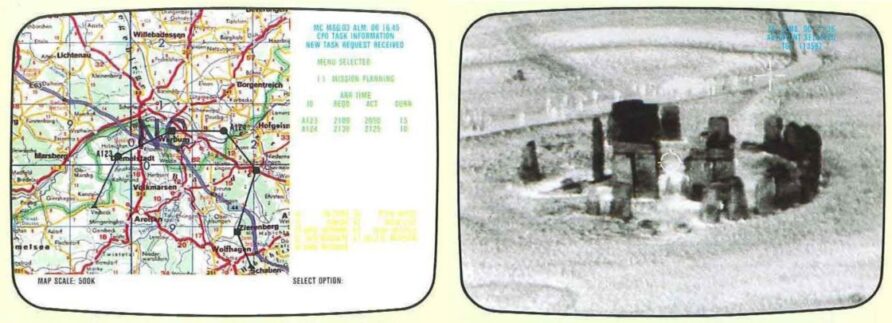

The Phoenix programme was initiated as a system to provide a real-time, day/night interface, to the Battlefield Artillery Target Engagement System (BATES). Initial studies for BATES started in 1976 and progressed to full project definition in 1980, entering service many years later.

Midge soldiered on.

Concept development contracts were awarded to four industry teams;

Marconi Aviation, Cranfield Institute of Technology and Flight Refuelling

A fixed-wing aircraft based on the Marconi Machan.

The Machan had a 12ft (3.66 m) wingspan with a 2-hour endurance and a 15 kg payload.

From this paper,

The first flight of MACHAN took place on the 27th November 1980, and it was the first remotely piloted vehicle in the world to have a full authority, all digital flight control system

British Aerospace Dynamics

A development of its Stabileye unmanned fixed-wing aircraft

Westland

A development of the Wideye, but one that used a low signature airframe.

Ferranti

Proposed both fixed and rotary wing platforms, a modified target drone from AEL and the Canadair CL-227.

Following completion of these development programmes in the early eighties, GST 3486 matured into GSR 3486, with real-time video imagery and the ability to retask in flight being key aspects.

Phoenix was primarily intended to provide targeting information for the 30 km range Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS), the first four of which had been purchased for delivery in 1985, from Vought Corporation for 5.2 million.

Both were linked, Phoenix finds, MRLS destroys.

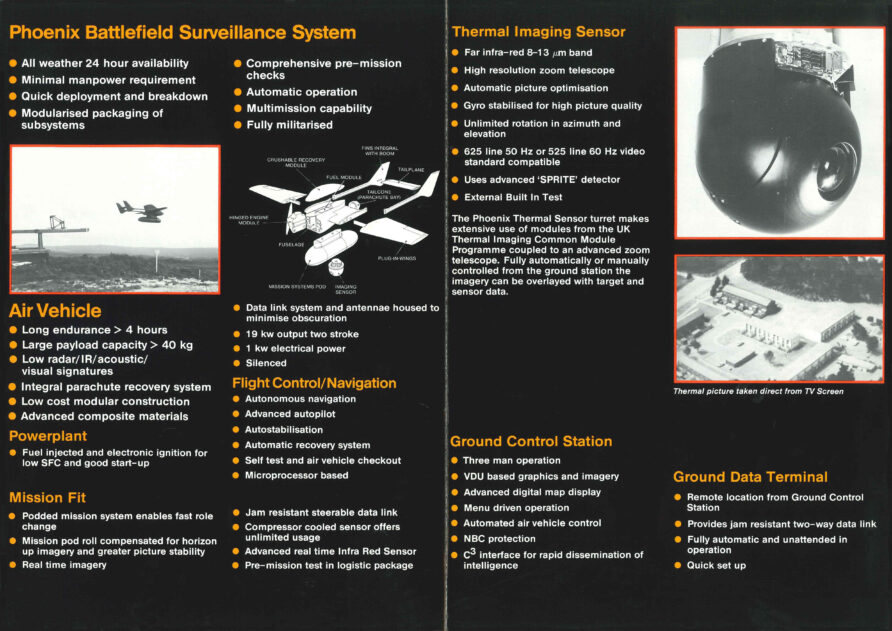

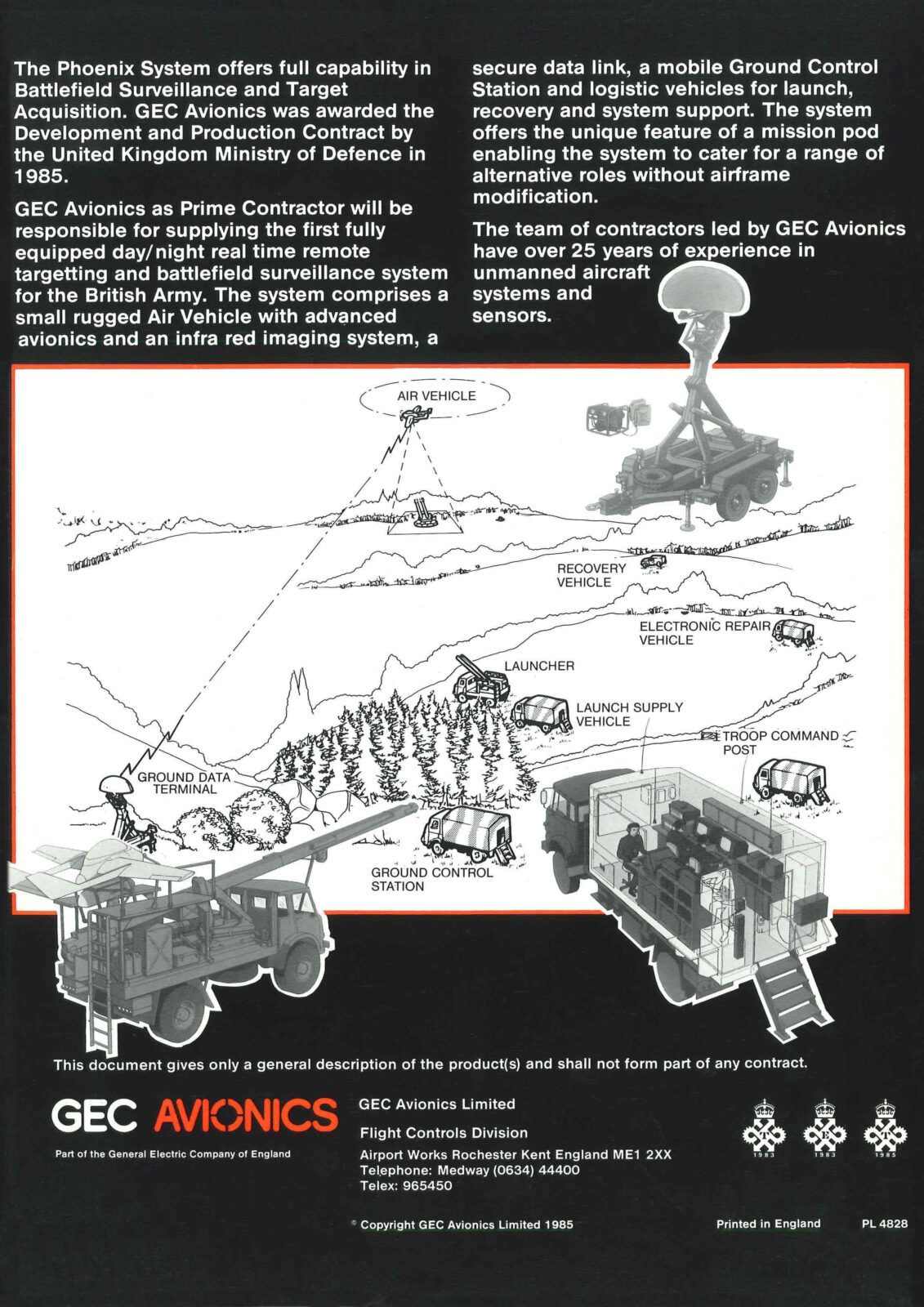

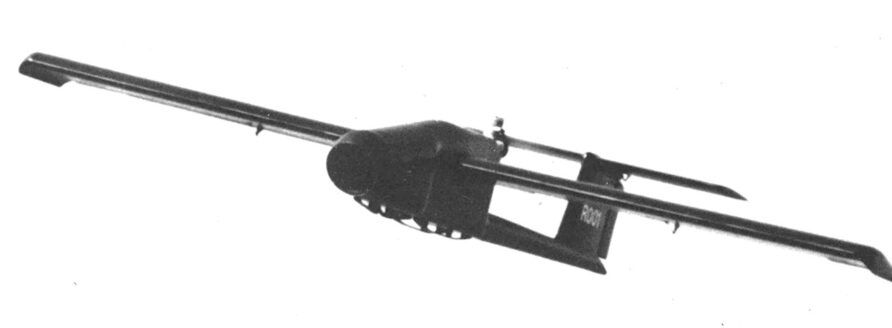

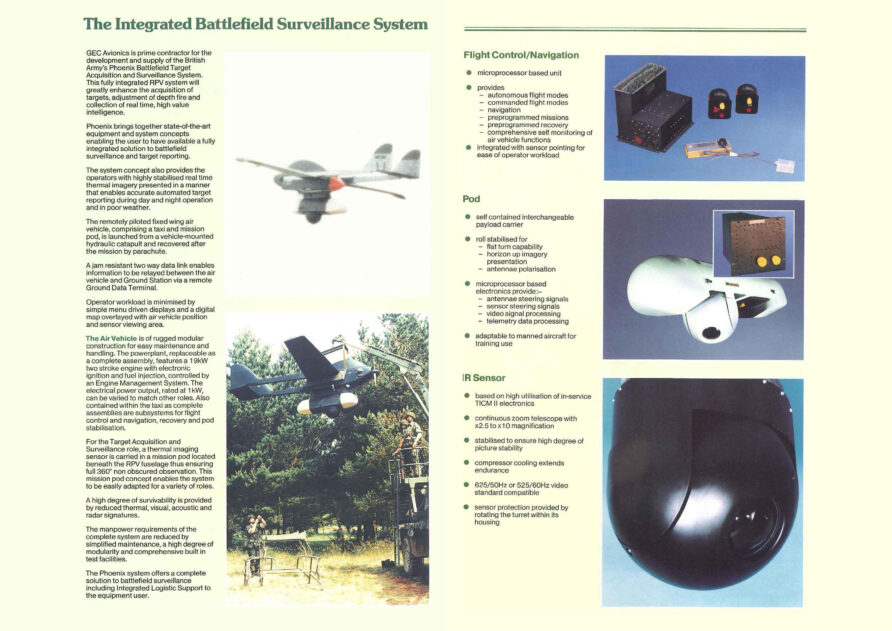

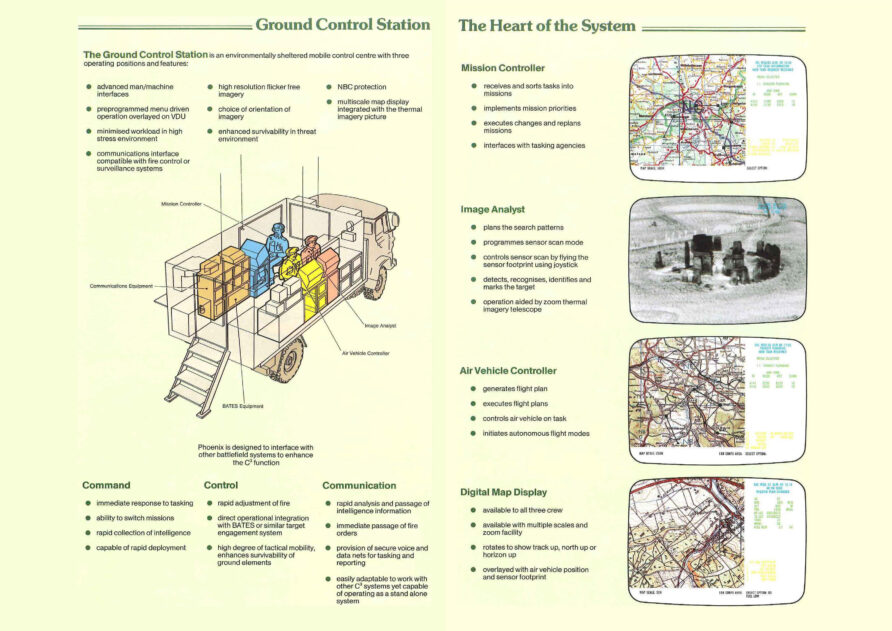

The £80 million Phoenix programme prime contract was awarded to GEC Avionics in 1985.

Flight Refuelling was to develop the unmanned aerial vehicle, powered by a Normalair Garret WAM 342 two-stroke two-cylinder engine.

In many ways, Phoenix was ahead of its time, recognising that the majority of the cost would be in the sensor, not the air vehicle.

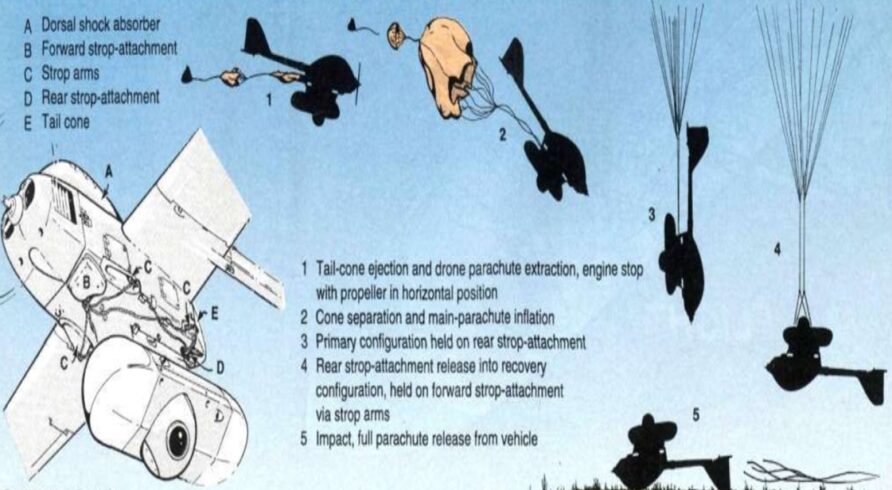

Therefore, to protect the expensive sensor, they were fitted into a demountable pod and the air vehicle landed on its back.

The landing would be cushioned by a frangible shock absorber.

The two were called the Air Vehicle Taxi (AVT) and Air Vehicle Pod (APD).

The launcher used a modified version of the All-American Engineering system used for the US Aquila system.

The payload included a daylight sensor and thermal imager (BAE Systems Thermal Imaging Common Module (TICM II)), both of which could be locked onto a ground location for continuous coverage whilst the air vehicle was moving.

The imagery was transmitted back to the ground control station using a steerable J Band data link.

As an aside, the Royal Navy also looked at vertical UAVs in 1988.

The ML Aviation SPRITE (Surveillance Patrol Reconnaissance Intelligence Target Designation Electronic Warfare) received funding from the Admiralty Research Establishment and conducted some trials onboard Royal Navy ships.

Alongside Phoenix, the British Army evaluated a smaller system from Flight Refuelling called Raven.

Raven, weighed 15 kg and was equipped with a day/night TV camera.

In 1995, the MoD considered cancelling Phoenix, it was by then six years late and estimated to cost double the approved contract value.

It was originally planned to enter service in 1989 and although accepted by the British Army in 1994, not a single one had entered operational service a year later, with problems persisting with the data link, ground control station computer systems and recovery equipment.

The project was not cancelled, but the MoD gave GEC Marconi 12 months to sort out the many problems with Phoenix.

One of the main problems was caused by harsh landings damaging the sensor pod, a change from a frangible hump to a slow inflating airbag was the eventual solution. A post-Gulf War proposal to incorporate a more powerful engine that could cope with weather apart from that found in Central Europe was rejected on cost grounds.

Despite the 12-month deadline imposed on GEC by the MoD in 1995, Phoenix came into service in December 1998.

It was also clear that despite the problems, Phoenix represented an opportunity to broaden its initial application in artillery support to a broader battlefield surveillance role, some investigation was also carried out to look at electronic warfare, laser designator and radio relay payloads.

As early as 1996, the British Army was thinking about a Phoenix replacement, a replacement that would be characterised by a step-change in endurance.

Phoenix had its first operational debut in Kosovo, where 13 of the 27 deployed were lost.

The deployment was widely considered to be a bit of a failure, despite Phoenix catching the Serbs in the act of flying MIG 21’s that had survived the NATO air campaign out of the airport at Priština.

On the ‘D-Day’….Phoenix detected 12 Mig-21s at Priština as the Serbs were withdrawing. These were detected at some considerable range. It is interesting that a previous [remote-piloted vehicle] had flown over the same location and had not located them; it had declared the area clear. [Phoenix] has a much better resolution than comparable systems. Now when the Russians occupied the airport, Phoenix overflew the complete area and was able to identify vehicles and give information on their activity. Because of the low cloud in that area, Phoenix was often the only UAV in-theatre that was able to provide any information on a regular basis. It was tasked with monitoring the ground security zone and it did that effectively. Prior to D-day, it conducted a search of all known Serb positions and this proved in fact in the majority of cases the Serbs had withdrawn. It gave our forces a tremendous capability which we did not have before.

Losses included two to enemy air action and three to training mishaps.

Operational use of Phoenix and other nations UAV’s in the Balkans clearly demonstrated their sheer usefulness and utility beyond the artillery spotting mission that had generally characterised similar tactical systems.

Much was also learned, the hard way, about operational management and control of UAV’s, especially in a complex air environment with multi-nation components.

The UK tried to circumvent the problem of slow authorisation by proposing to use a forward air controller in a Phoenix ground control station to direct Harrier GR7 strikes but the USAF senior leadership in the Combined Air Operations Centre (CAOC) refused to sanction the idea unless a satellite link could be installed to allow the CAOC to view the imagery and give the final authorisation for any strike.

Needless to say, we ran out of war before the red tape could be untangled.

Operations in the Balkans also exposed slow and predictable UAV’s to the enemy ground and air attacks, the Serbs even had some success with flying a helicopter parallel to the airborne systems and simply machine-gunning them out of the sky.

Perhaps the biggest lesson learned from the operational use of UAV’s in the Balkans, apart from their vulnerability to even half-competent air defence forces, was the difficulty of matching a strategic air campaign to what were in effect, tactical assets, being used in an operation for which they were not designed for.

A few years later, during Operation TELIC, the Phoenix UAV had another brief moment in the sun.

Despite its relatively poor showing in the Balkans, Phoenix was credited by General Brimms (GOC 1(UK) Armoured Division), along with Challenger and Warrior, as being the top 3 war-winning assets in the initial stages of the Iraq war, Operation TELIC.

The Phoenix provided for the first time situational awareness commanders had not had access to before. We flew in front of the commandos before they went into attack and provided up to date, real-time information to commanders on the ground, enabling them to make key decisions before they went into battle and during the battle itself

The loss figures were not good.

During the 138 sorties carried out by Phoenix in Iraq by 22 (Gibraltar) Battery, 23 were destroyed with 13 damaged, only 15% of these losses were due to enemy action.

The hot weather caused considerable problems which rendered it unusable from May onwards, and enduring problems of radio interference on the data link were never resolved.

The problems of hot weather operation, considered in 1995, were realised in an operational theatre.

The last operational flight of Phoenix was carried out by Koehler’s Troop in May 2006, at Camp Abu Naji in Iraq.

Phoenix was withdrawn from service in March 2008, the image below shows the out of service parade at Roberts Barracks, Larkhill, on the 20th

The estimated cost was £260 million.

Whilst many argue Phoenix was a failure, I would counter that it demonstrated the value of UAV’s, enabled some significant battlefield success, and further established valuable expertise and experience.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Watchkeeper Programme History

The Watchkeeper story starts with the 1998 Strategic Defence Review, in which a break from the Cold War was described and a move to an expeditionary strategy proposed.

Britain’s place in the world is determined by our interests as a nation and as a leading member of the international community. Indeed, the two are inextricably linked because our national interests have a vital international dimension. The British are, by instinct, an internationalist people. We believe that as well as defending our rights, we should discharge our responsibilities in the world. We would rather not stand idly by and watch humanitarian disasters or aggression of dictators go unchecked. We want to give a lead, we want to be a force for good.

It also recognised the importance of information and surveillance capabilities, pointing the Phoenix as an exemplar (stop laughing at the back)

By the time the Strategic Defence Review New Chapter was published in July 2002, Watchkeeper was on the scene.

A key element in network-centric capability involves the use of unmanned air vehicles (UAVs), equipped with appropriate payloads and data links. The US demonstrated in Afghanistan how effective such systems can be in providing persistent surveillance of the battlefield or theatre of operations, without putting aircrew lives at risk. Our own Watchkeeper project has the same purpose, and we intend to accelerate the programme.

UAVs offer huge potential for improving operational effectiveness, in a range of different situations and environments. We cannot anticipate all their capabilities and uses, or indeed limitations, ahead of putting them in the operator’s hands. Our own experience of the Phoenix system in the Balkans was instructive. Designed and deployed as an observation system for artillery, it rapidly proved its utility in a much broader surveillance role.

Accordingly, we have decided to establish a joint-Service UAV operational development unit, in which personnel from all three Services will acquire early experience of exploiting such systems, in different configurations and conditions and with different payloads. Details of the composition and location of the unit are still being developed, but we expect to select next month the two consortia to work with us on the next phase of the Watchkeeper project, and we shall invite each of them to provide us with an appropriate prototype system in short order, to enable practical experimentation to begin in the first part of next year. Lessons and experience can then be fed back into refining our requirements and understanding of UAVs potential as the Watchkeeper programme develops

DERA (with Cranfield Aerospace and Tasuma) had demonstrated the Observer system to serve as a test bed for future systems, and this flew in late 1999.

The first flight of a new unstable air vehicle design took place on the 11th March 1999, at DERA, Shoeburyness. It was a propeller-driven gust insensitive configuration called OBSERVER, with a nominal AUW of 30 kg and a span of 2.42m. It flew under pilotless automatic control from launch until just prior to touch down when a ground pilot was used, via the attitude demand control system, to complete the skid landing.

Based on elements of the Cranfield Aerospace XRAE1 UAV, it was rail launched and parachute recovered.

The Observer system was a short-range and short endurance system, but it incorporated advanced flight control and sensor systems that would form part of the deliberations on future systems.

Observer work was carried out under the Battlegroup Unmanned Aircraft (BgUMA) programme

BgUMA eventually evolved into two discrete requirements, SENDER and SPECTATOR.

To complicate matters, SENDER was also part of the emerging reconnaissance trio, the others being ASTOR and the TRACER armoured reconnaissance vehicle.

This was actually logical and fully coherent, although it did make the programmes somewhat complicated and ambitious.

SENDER was a battalion relevant system with a 30 km range and an electro-optical and IR sensor payload, SPECTATOR, a larger system designed for higher levels (/Brigade/Division) than SENDER with a 150 km range and dual electro-optical and synthetic aperture radar payloads.

SENDER was also intended to have minefield detection and electronic warfare payloads.

The MoD invited twelve companies to bid for the Sender unit UAV assessment phase in 1999.

The Draft ITT was issued to Aérospatiale Matra, Bell Textron, GKN Westland, Hunting, Thomson-CSF, Lockheed Martin, Matra BAe Dynamics, Northrop Grumman, Racal, Raytheon and TRW.

A number of the teams proposed the Bell Eagle Eye tilt rotor and the IAI Searcher.

Four companies were to be down-selected with the equipment intended to enter service in 2008.

Also in 1999, the MoD and DoD agreed on a letter of intent to explore joint development opportunities for tactical unmanned systems. The MoD also described a requirement for a data link relay vehicle programme called EXTENDER.

As the twelve competing organisations were readying their bids, the MoD decided to merge Sender and Spectator into a new programme, called Watchkeeper, once the link to TRACER had been broken. There are conflicting reports about this, some indicate that Sender and Spectator informed Watchkeeper, others, that they were cancelled to provide Watchkeeper with a clean slate.

The user requirement statement was;

Watchkeeper is required to provide accurate, time and high-quality IMINT, collected, collated, exploited and disseminated to satisfy land manoeuvre commander’s critical information and intelligence requirements within the context of joint operations throughout a range of environments and across the spectrum of conflict.

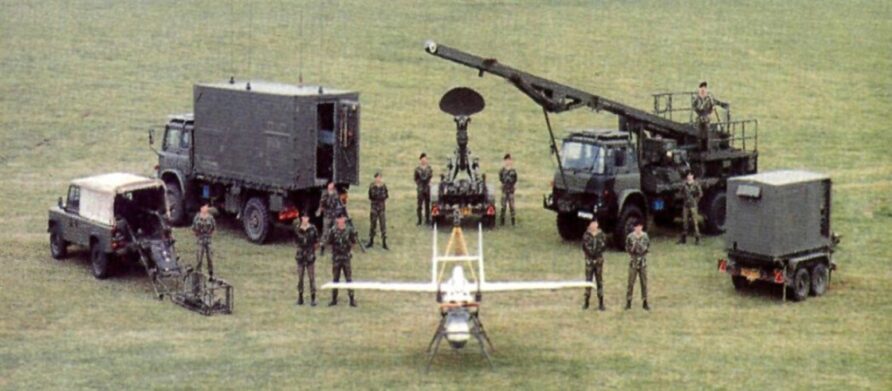

In 2000, the MoD awarded £3.5 million study contracts for Watchkeeper to BAE, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Thomson Racal Defence.

BAE; Proposed the RQ-1 Predator and AAI Shadow

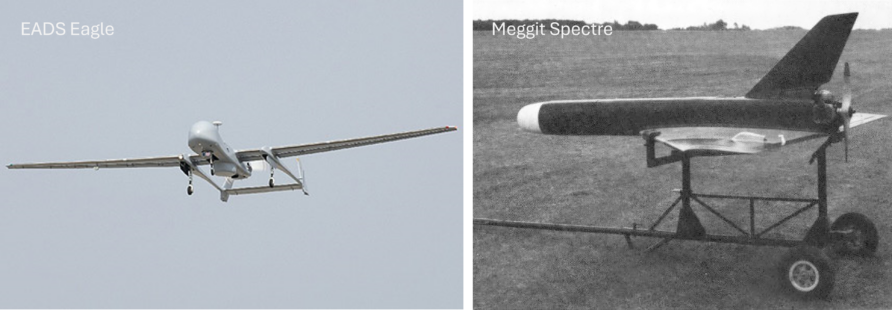

Lockheed Martin; The EADS Eagle and Meggitt Spectre 3

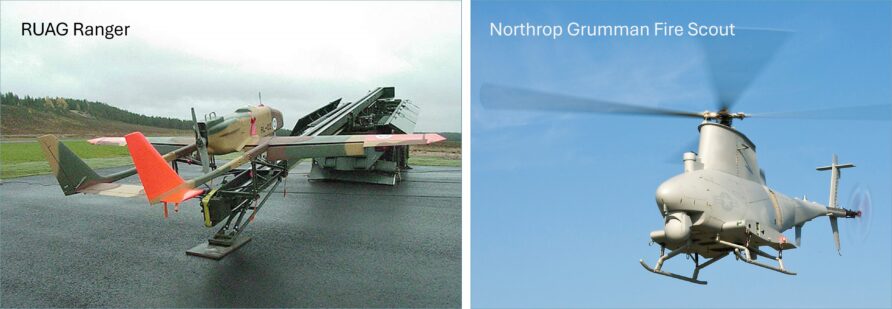

Northrop Grumman; The Fire Scout and RUAG Ranger

Thales; The Lydian Hermes 450 and 180.

Watchkeeper was notionally a British Army capability but, as with FRES and many other projects at the time, there was a joint element.

With experience from Kosovo still relatively fresh, the RAF were reportedly interested in its bomb damage assessment and target designation capabilities.

For the RN, the Watchkeeper User Requirements Document (URD) included a range of maritime and littoral battlespace capability requirements, in addition to applicability for a maritime deployed force (Royal Marines).

In 2001, the MoD indicated that Watchkeeper was to be accelerated, with a planned FOC in 2007 and IOC in 2005.

Assessment Phase contracts were let to BAE Systems, Lockheed Martin, Thales and Northrop Grumman, after which two would be down-selected.

The original SENDER and SPECTATOR split requirement was retained, although the range and endurance of the SPECTATOR were increased considerably.

Raytheon and General Atomics conducted a study on the feasibility of controlling an RQ-1 Predator using the ASTOR mission system, they suggested this capability could be rolled into Watchkeeper.

Two consortia were down-selected in 2003 for the Systems Integration Assurance Phase;

Two industrial consortia have been selected for the next stage of the multi-million pound Watchkeeper (UAV) programme, which will provide surveillance and reconnaissance on the future battlefield.

The New Chapter of the Strategic Defence Review, published last year highlighted the key part that UAVs will play in contributing to network enabled capability, in order to improve our ability to find, identify and act decisively against the enemy. UAVs will be linked with ‘strike’ systems, including artillery, army attack helicopters or ground attack aircraft.

Teams led by Thales UK and Northrop Grumman ISS International have been selected to carry forward parallel assessment phase work before the selection next year of the preferred bidder for the £800m Watchkeeper programme.

Lord Bach, Minister for Defence Procurement, said:

“Watchkeeper unmanned air vehicle systems will be an invaluable addition to our military capability. They will play a vital role in providing our armed forces with timely intelligence to identify the threat, enabling us to strike faster and more decisively. Military commanders will be able to get high-quality images as Watchkeeper tracks targets right up until the moment they are destroyed.

“Watchkeeper will have a huge impact in providing our forces with the best capability, as cost-effectively as possible.”

Watchkeeper is planned to be in service for 30 years, with an initial operating capability in early 2006. The Watchkeeper programme will be complemented by the Joint Service UAV Experimentation Programme (JUEP), which will assess the wider operational use of UAVs in the tri-service battle environment

Northrop Grumman ISS International; teamed with General Dynamics, BAE Systems, Ultra Electronics, Detica and STASYS to offer the Fire Scout and RUAG Ranger air vehicles.

Thales-UK; with Aerosystems International, Cubic, Logica CMG, Vega, Marshall Special Vehicles, Elbit, and QinetiQ offering the Hermes 180 and Hermes 450 air vehicles.

The statement of user requirement did not actually specify weights or indeed that an unmanned solution should be proposed but a collection of requirements for persistence, all-weather operations and deployability.

£8m contracts were awarded to the two down selected bidders for risk reduction work.

In April 2004, the US Government approved the export of the General Atomics/Sandia National Labs developed Lynx synthetic aperture radar (SAR) for use on a future Watchkeeper air vehicle, not the RQ-1 Predator as proposed by BAE because they had not made the down select cut.

In July 2004, Thales was selected as preferred bidder and the contract award was in 2005 with a planned in-service date of 2007.

It was also announced that the smaller vehicle would now no longer be part of the programme, although subsequent deployment/UOR purchase of the Lockheed Martin Desert Hawk UAV would tend to confirm an enduring requirement.

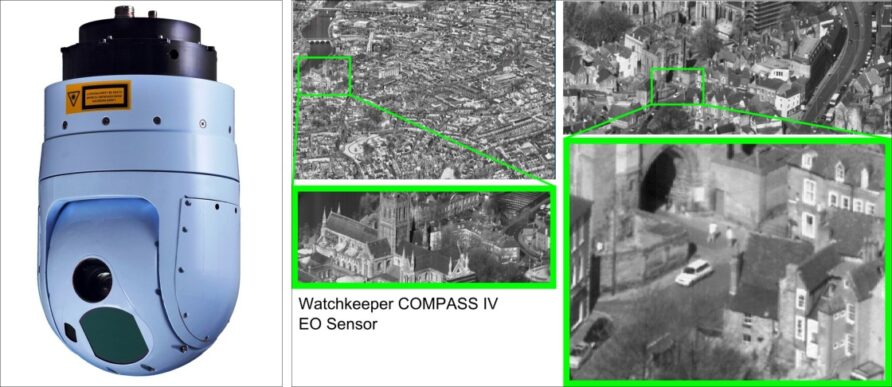

Thales announced the Watchkeeper sensor package in 2005;

El-Op and Thales UK land and joint systems in Taunton, have been awarded a multimillion pound contract by Unmanned Tactical Systems Ltd (U-TacS) of Leicester for the CoMPASS electro-optic system. This system, containing El-Op’s cutting-edge electro-optic sensors, delivers enhanced high-quality day and night imagery, laser range finding, target designation and marking. It offers superior stabilisation performance, highly accurate Line of Sight (LOS) positioning capability and precise LOS angular and range data.

A multi-million-pound contract for the I-Master radar package has been awarded to Thales UK’s aerospace business in Crawley. I-Master is the only lightweight high performance combined Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and Ground Moving Target Indicator (GMTI) in its class. Weighing only 30 kg, I-Master provides the perfect balance of capability, cost, weight, and power consumption for use onboard unmanned air vehicles (UAV), helicopters and small fixed wing aircraft. High-performance imaging radars are now essential in any programme that requires an all-weather ISTAR capability. To date, high-quality SAR/GMTI radars have been too heavy and costly to be carried as a dual payload in tactical UAVs.

I-MASTER provides an all-weather capability, which dramatically increases tactical UAV mission effectiveness. I-MASTER incorporates both high-resolution SAR and a high-performance GMTI able to detect both vehicle and infantry movements.

Watchkeeper would be a single air vehicle with a two-sensor payload and a ground control station mounted on a Supacat vehicle that could be carried onboard a c-130 Hercules.

Over the next couple of years, several vendor contracts were announced as the project progressed, QinetiQ for example;

The work package will include carrying out a variety of airborne test and evaluation elements at Parc Aberporth over the next 18 months and the adjoining MOD Aberporth air range. Various ground-based work will also be conducted using QinetiQ operated facilities at MOD Boscombe Down to enable a range of pre-flight activity including environmental and electromagnetic compatibility testing. This work supports and augments the wider UAV development programmes currently being investigated by QinetiQ and other Industry players along with the MOD. The contract will be administered through the West Wales UAV Centre, the teaming between QinetiQ and West Wales Airport, established a year ago to deliver UAV support services for both civil and military customers.

In 2007, the UK acquired Predator B/Reaper under an urgent operational requirement.

As a stop-gap for use in Iraq and Afghanistan, the MoD obtained a number of Hermes 450’s from Thales UK in 2007 under Project Lydian, operated by a military/civilian mix of personnel.

Civilian personnel managed the take-off and landings, whilst members of 32 Regiment RA took control of the mission.

This Urgent Operational Requirement covered 5 task lines.

Some operational and logistic experience was also fed back into the main programme.

The equipment was provided by Thales on a ‘by the hour basis’ and the 6 air vehicles collected the majority of airborne imagery used in theatre by UK forces.

In a 2007 memo to the Defence Select Committee, the MoD described the then current status;

Main Gate approval was given in mid-2005. Watchkeeper is currently expected to reach Initial Operating Capability in the second half of 2010 and to reach Full Operating Capability in 2013. The system is being developed from the Hermes 450 system currently operating in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The programme is due to deliver (including attrition stock) 54 air vehicles and 15 GCS and will provide the capacity to conduct up to 12 concurrent missions (or “lines of tasking”). It will be operated by 32 Regiment, Royal Artillery. Watchkeeper is intended to support Land operations and is capable of carrying simultaneously three types of sensor: electro-optical/infra-red FMV; SAR [Synthetic Aperture Radar]; and GMTI [Ground Moving Target Indication]. In addition, it will carry a laser rangefinder/target marker.

It will have UK-specific data links, have an automatic take-off and landing capability and be able to use tactical landing strips.

Overall, Watchkeeper provides greater capability compared to Hermes 450 and, subject to operational circumstances at the time, the intention is that it will start to take over from Hermes 450 from 2010.

Watchkeeper first flights…

April 16th 2008, Megiddo airfield, Israel

Parc Aberporth, Wales, 2010

Details of a possible weapon carriage capability emerged in 2009, likely a Thales Lightweight Multirole Missile (LMM), or a free-fall variant.

Meanwhile, the in-theatre Hermes 450 contract was extended to 2011, by which time Watchkeeper was still scheduled to be in service.

In addition to the first flights above, 2010 saw the award of a three-year £55 million support contract to Thales UK.

Flight testing continued, in 2011, Watchkeeper flew a 14-hour flight in which it was flown to its service ceiling of 4,880m (ca. 16,010 ft) and 115 km from the West Wales Airport.

The two sensors and data links were also tested.

It was also planned for Watchkeeper to be deployed using Viking tracked vehicles.

France and the UK signed a defence cooperation treaty in 2010 at Lancaster House, central to the agreement was that France would evaluate Watchkeeper from 2012 with a view to its requirements for a similar capability.

In Afghanistan, a Hermes 450 ZK515 crashed.

The resulting Service Inquiry made for uncomfortable reading for the Royal Artillery, making a total of 61 recommendations.

In 2011, it was announced that Watchkeeper would be deployed to Afghanistan the following year.

A December 2012 Parliamentary Answer clarified the position on arming Watchkeeper and maritime operations;

Mr Ellwood: To ask the Secretary of State for Defence what his policy is on the use of the Watchkeeper unmanned aerial vehicle by the British Army; whether there are any plans to (a) arm the Watchkeeper and (b) consider it for operations with the Royal Navy; and if he will make a statement. [130659]

Mr Dunne [holding answer 29 November 2012]: Watchkeeper is a tactical unmanned air system that will provide battlefield commanders with an all-weather intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance capability. There are no plans currently to arm Watchkeeper, and although the Army may use it in support of littoral operations, we have no plans to operate the system from Royal Navy or Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessels.

By the end of 2013, the leased Hermes 450’s had flown over 70,000 hours across 5 task lines.

2013 also saw a significant milestone with the award of its Statement of Design Assurance (STDA) from the Military Aviation Authority (MAA).

This was a result of a tailored process, the full process being defined after Watchkeeper had been started.

By the end of operations in Afghanistan, the contract Hermes 450’s had flown 100,000 hours.

Release to Service certification for Watchkeeper was still a year away.

In March 2014, the MoD announced that Watchkeeper had been given clearance to begin flying training in the UK with Royal Artillery aircrew.

Approval has been given for the Army’s own pilots to begin live-flying the unarmed Watchkeeper from Boscombe Down in Wiltshire; up until now, it has been only been trialled by industry.

Gathering crucial information from the battlefield, Watchkeeper will provide UK troops with life-saving surveillance, reconnaissance, and intelligence. It will also give personnel on the ground much greater situational awareness, helping to reduce threats.

Over the coming weeks, highly skilled 1st Artillery Brigade pilots will be trained to fly Watchkeeper in a restricted airspace over the Salisbury Plain Training Area. The flights, which will take place between 8,000 and 16,000 feet, will be overseen by military air traffic controllers.

This Release to Service allowed flying training from the QinetiQ facility at Boscombe Down, shown below.

It was also reported that all the ground stations and half of the 54 air vehicles had been delivered to the Army.

Commenting on the announcement, Michael Fallon M (Secretary of State for Defence) said;

Watchkeeper is the first Unmanned Air System developed and built in the UK to become operational and will be a significant surveillance and reconnaissance capability for the Army for years to come.

In October 2014, it was revealed that Watchkeeper had deployed to Afghanistan.

The Army’s next generation of Unmanned Air System (UAS) – Watchkeeper – is now fully operational in Afghanistan. This new capability is providing force protection for British troops as they prepare to draw down from Afghanistan by the end of the year.

Gathering crucial information from the battlefield, Watchkeeper, which is unarmed, will provide UK troops with life-saving surveillance, reconnaissance and intelligence. It will also give personnel on the ground greater situational awareness, helping to reduce the risk of threats.

Watchkeeper pilot Sgt Alex Buchanan said: “It’s been a real privilege to be the first to fly the Army’s new Watchkeeper Remotely Piloted Air System on operations. It’s an amazing capability and has already provided important information to the troops, enhancing the safety of everyone that lives and works at Bastion. “The video and images we provide are a bit like what you might have seen during police chases on TV, the main differences are the videos and pictures are a much higher resolution and we fly the aircraft from a control centre on the ground.”

The deployment was to cover the withdrawal of forces and, specifically, utilised the i-Master SAR to counter dust storm blackouts experienced by visual systems.

Three air vehicles flew for a total of 146 hours.

Initial Operating Capability 1 was achieved in 2014.

Commenting on the Afghanistan deployment ahead of the 2015 Paris Air Show, Lieutenant Colonel Craig Palmer, SO1 UAS Army HQ, said;

Watchkeeper has been a step-change in how the British Army does information superiority.

Afghanistan was a real success for us, and we are now looking to continue to develop the programme [back in the United Kingdom]. We can now do things with ISTAR that we could never previously do. I believe that the I-Master is the real game changer here, and what has given the Watchkeeper such a great capability. For example, the combination of GMTI and SAR from the same [Watchkeeper] platform … provided pattern-of-life intelligence which showed if a trail that was normally used [by the locals] was no longer being so because it had been seeded with [improvised explosive devices

He also commented on the number of air vehicles compared to the number of deployed systems;

We’ve been in danger of becoming a little too precious of UAS — they were originally conceived to fly into harm’s way without danger to the pilot. In fact, we lost over 30 Phoenix UAS in Iraq precisely because we flew them against integrated air defence systems. Attrition has been built into the [Watchkeeper] contract to allow for future use in a high-threat environment.

I think he may have been over-egging the causes of Phoenix losses, only 15% of those losses were attributed to enemy action, and none of them because they flew into the teeth of an integrated air defence system.

Freedom of Information requests in 2015 revealed the shortage of pilots for Watchkeeper, as of November 2015, only 4 military and two civilian pilots were certified to fly Watchkeeper.

It was planned for 24 to be available by the end of 2017, broadly speaking, the same as at FOC.

Only 8 aircraft were in regular use, with the rest in storage, although there are 24 trained launch and recovery personnel and 20 maintainers.

One of the most significant challenges (and source of delays) was the desire to achieve certification to fly in civil airspace.

The Watchkeeper Project CLAIRE (CiviL Airspace Integration of RPAS in Europe) flight demonstration was completed in September 2015, showing that it could fly alongside a manned aircraft in civil airspace.

This doesn’t sound much in words, but it was an immense challenge.

The flight took place on Wednesday 30 September and saw Watchkeeper fly from West Wales Airport into civil controlled airspace for an hour, where it was successfully managed by NATS, the UK air navigation services provider, for the first time.

The flight forms part of Project CLAIRE, a collaboration between Thales, NATS, the Dutch National Aerospace Laboratory NLR, the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and was jointly funded by the SESAR Joint Undertaking.

This new breakthrough is once more an innovative step for Watchkeeper, the largest single European UAS programme, having already been the first UAS of its type to be awarded a Release to Service (RTS) or equivalent in Europe.

Its type assurance and certification allow Watchkeeper to fly in non-segregated airspace, a certification pedigree that is transferable to regulatory authorities within other NATO member countries and the European Aviation Safety Agency.

Using Watchkeeper, this aviation first will help develop the necessary operational and regulatory conditions to support a growing need for unmanned aircraft system to be used in commercial, search and rescue, homeland security tasks, critical infrastructure and border protection.

Air Commodore Pete Grinsted, Head of Unmanned Air Systems Team at the MOD’s Defence, Equipment and Support organisation, said: “This is a landmark achievement for UK aviation history and the Watchkeeper programme, and was only possible thanks to a collaborative approach involving Thales, CAA, NATS and the MOD.

“The successful flight is the result of months of systematic planning to ensure Watchkeeper was safely controlled by UK Air Traffic Control agencies at all times. This is also an exciting step on the path to safely integrating military and civilian unmanned air systems into civilian airspace over the coming years.”

This flight together with the successful delivery of Watchkeeper into service demonstrates how Watchkeeper X, our tactical product, based on the British Watchkeeper programme, provides a strong solution to meet the requirements of both France’s UAS programme and Poland’s Gryf Tactical UAS programme.

The flight lasted over three hours, including one hour in non-segregated airspace.

In October 2015, a representative from the Civil aviation authority provided additional information on the first flight described above;

However, Gerry Corbett, the CAA’s programme lead for UAVs, told the Commercial UAV Show in London on 20 October that it was only a demonstration, and a lot of planning and funding was required in order for the British Army aircraft to be permitted to carry out the sortie.

“It doesn’t mean that Watchkeeper is now routinely flying through controlled airspace,” Corbett says. “This was, after all, a military aircraft with ‘army’ written down the side.”

Watchkeeper is certified to fly in controlled airspace, but Corbett noted that its single engine would prevent this being a routine operation for safety reasons: “As soon as that engine fails, it would drop out of the airspace. We ended up putting lots of temporary danger zones underneath the flight path”. Regarding the Watchkeeper test, Corbett adds that another flight was planned, but that bad weather stopped it from happening.

On the 2nd of November 2015, a Watchkeeper air vehicle suffered extensive damage during a landing mishap at Boscombe Down, the third to date. In the other two incidents, one air vehicle was written off and the other, repaired.

Following the 2015 SDSR, several changes were made in the organisation of unmanned systems in the Royal Artillery.

The main change was a move from integrated unmanned regiments to single system regiments. Previously, 32 Regiment and 47 Regiment operated both Watchkeeper and Desert Hawk, going forward, 32 Regiment would operate Desert Hawk and 47 Regiment, Watchkeeper.

47 Regiment was also planned to resubordinate from 1st Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Brigade (1ISRX) to the command of Joint Helicopter Command (JHC), this allowing the Watchkeeper force to take advantage of the air safety resources within JHC.

43 Battery 47 Regiment started a period of Watchkeeper flying training on Ascension Island to take advantage of better weather and infrequent manned flights, in many ways, it is an ideal location for unmanned aircraft flying training.

FOC was planned for 2017 with an OSD of 2042.

Although the National Audit Office stopped reporting on Watchkeeper several years ago, the Major Projects Authority does provide some financial and project information.

The Project Lydian contractor provisioned Hermes 450’s for Afghanistan cost a total of £206 million.

Watchkeeper Assessment Phase costs were £65 million, Demonstration and Manufacture Phase, £839 million.

Whole life costs currently include the Development, Manufacture, and Initial Support of the Watchkeeper System. This includes the delivery of Equipment (54 Air vehicles and 15 Ground Control Stations), contractor logistic support, and initial training delivery of Watchkeeper Operators and Maintainers. Costs are based on a mix of Firm Price Elements (£1145.36M) and an estimate (risk assessed) for the completion of programme activities (£22.2M). Changes since Q2 2013/14 are attributable to the deferred deployment of Watchkeeper to Afghanistan, where activities required re-profiling. There has also been a technical adjustment to the way costs are reported, resulting in an apparent reduction in costs — budgeted Whole Life Costs are now reported out to Full Operating Capability (2017) rather than up to 2023/24

Watchkeeper was certainly late, by several years.

Initial Operating Capability 2 was achieved in 2016.

During the project definition phases, it was envisaged that full operating capability could be achieved in 2007.

The MPA describes status as in 2017 as;

The programme was re-baselined in June 2014. The first major milestone (Initial Operating Capability) was achieved by deploying the capability to Afghanistan in August 2014 at the Operational Capability Unit (OCU) standard. The next milestone is to generate additional capacity of 4 Task Lines (at the OCU standard) in April 2016. The main effort is to achieve Full Operating Capability (FOC) Apr-Jul 17 with an uplift of the capability to Equipment Standard 2 (ES2). This will require a major Release to Service (RTS) amendment. The programme remains on track to achieve these milestones. Achieving programme milestones remains challenging, but the re-balancing process has delivered a taut and achievable timeline.

If FOC was to be achieved in 2017, it would be 17 years after the initial concept contracts were awarded.

Issues were many, certification, software and de-icing systems all proved to be problematic.

Changes were also been made to the underlying requirements as a result of an experience in Afghanistan.

In July 2016, Cubic was awarded a contract extension from U-Tacs for their data link

Cubic Mission Solutions (CMS), a newly formed business division of Cubic, today announced a three-year extension award of $1.4 million from UAV Tactical Systems (U-TacS) to provide additional Tactical Common Data Links (TCDL) for UK Ministry of Defence’s (MOD) WATCHKEEPER Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) programme. The WATCHKEEPER programme, which is recognised as one of Europe’s largest and most extensive UAS programmes, provides UK Armed Forces with essential Intelligence, Surveillance, Target acquisition and Reconnaissance (ISTR). Cubic’s high-speed and secure TCDL serves as the wireless connection for transferring data and images from UAS to ground control stations. The TCDL leverages digital signal processing to accept and process high-volume sensor data generated on the air vehicle for transmission to its ground stations. A simultaneous uplink transmits control commands to the air vehicles and its payload

Furthermore, in July 2016, the MoD awarded another £80 million support contract to Thales.

The UK Ministry of Defence has awarded Thales a £80 million contract to deliver Support to the British Army’s combat proven Watchkeeper Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS). The Support Contract will provide technical support over the coming years and provide important additional capacity for training in order to generate operational capability. Training support will see the continuation of the Watchkeeper Training Facility, training solutions design, updates to training courseware, and additional instructional capacity for pilot and mission system operators, maintainers and support crew.

In addition to supporting force generation, through training, Thales will provide direct maintenance support, which includes the provision of trained personnel to enhance the Army’s front-line engineering capacity.

Other important areas of support include a flexible, responsive technical query service; maintenance and updates of technical documentation and supply support, and the repair and deep storage maintenance for the equipment held in reserve.

The award of this contract will sustain around 160 high-quality engineering jobs at locations across the UK including Crawley, Leicester, Bristol and Boscombe Down.

The Service Inquiry into the loss of a Watchkeeper air vehicle on 16th October 2014 at West Wales Airport was released in August 2016.

The Army was planning to have thirty air vehicles in operation and twenty-four in reserve.

A review of all major projects in 2017 concluded that the system should remain in service and development.

Full Operating Capability (FOC) was achieved in 2018, 5 years later than agreed in the Main Gate Business Case

A £125m 5 year support contract was let to Thales in 2019.

A July 2020 Written Answer described how many were in service

45 Watchkeeper airframes were in service as at 23 July 2020. 13 have flown in the past 12 months and 23 have been in storage for longer than 12 months. Of those flying, 10 have been operated by the Army from Akrotiri in Cyprus and Boscombe Down in Wiltshire, three have been used for test and evaluation. The airframes in storage are held at specific, graduated, levels of readiness. This is commensurate with practices used on other Defence capabilities and assets

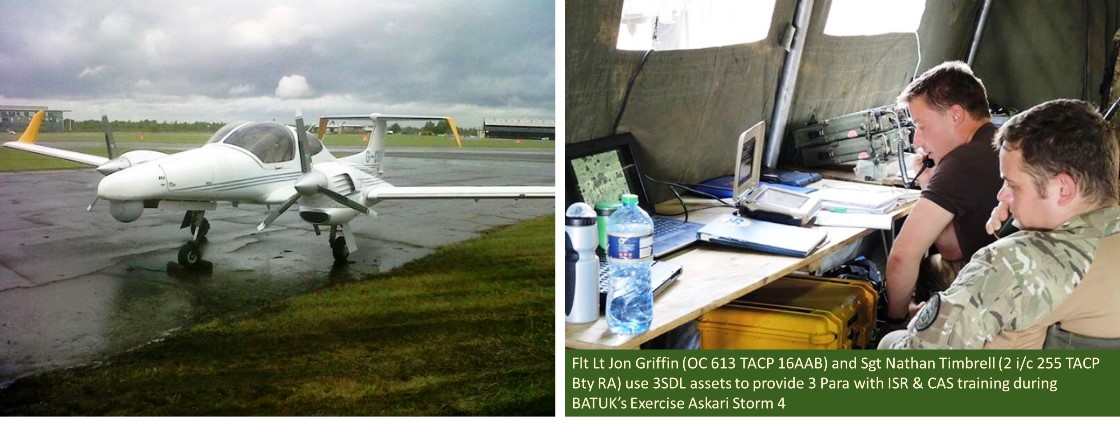

For the British Army in Kenya, 3DSL provided Diamond DA42’s in the role of surrogate unmanned air vehicles.

Thales was leading an export push for Watchkeeper, branding it Watchkeeper X (WKX). The WKX variant removed UK specific content and allows customers to specify a range of payload and systems components.

“Watchkeeper X is based on a groundbreaking, world leading unmanned aircraft system that was designed specifically for the requirements of the British Army. There is no other capability like it available in today’s market. We have now taken the knowledge and expertise that we have gained over the history of the programme and looked at how we can make it more flexible, effective and readily available for our customers, to help them address the different operational contexts they may face.”

Pierre Eric Pommellet, Thales Executive Vice-President, Defence Mission Systems

Thales also marketed a shipborne Ground Control Station (GCS) and several alternative payloads such as maritime surveillance radar, communications intelligence systems (COMINT), radar electronic support measures (RESM), and cryptographic electronic support measures (CESM).

For the French requirement, Thales proposed a new 1920 × 1080 camera from L’Heritier (rather than the 720 version on Watchkeeper), a French data link and full compatibility with French C4ISR systems.

For Poland, Thales proposed using several Polish integrators and arming it with four free-fall LMM’s. It was also suggested that Poland would finance the purchase through a UK Government guaranteed loan.

France eventually selected the Sagem Patroller instead of Watchkeeper.

For the UK, the main focus has been maturing it in service, beyond that, SIGINT or other payload improvements might be delivered through a spiral development programme, perhaps even arming them, these do seem some way off, though.

Watchkeeper X was selected by Romania in 2023, with deliveries scheduled for 2025.

By the end of 2021, Watchkeeper had flown a total of 2,778 hours since its release to service in 2014. with six being lost to accidents.

In October 2024, the British Army reported on a Watchkeeper deployment to Estonia, Exercise Athena Shield

The British Army’s most farsighted eye in the sky has taken flight in the skies of Estonia.

The Watchkeeper Uncrewed Air System (UAS), flown by 47th Regiment Royal Artillery, has had a recent upgrade of the sensors it uses when flying intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance (ISTAR) missions.

Working alongside our Estonian colleagues has been a great experience and many lessons have been learnt in the planning of flying operations in the country. It has also demonstrated the Army’s commitment to supporting the Estonian Defence Force and securing NATO’s Eastern Flank.

Image of the deployment below.

In November 2024, the MoD announced plans to withdraw Watchkeeper

The UK will speed up the decommissioning of old military equipment to save up to £500m over five years, the government says.

Defence Secretary John Healey told the House of Commons that the move would free up funds for further investment in the armed forces, in line with the government’s target of spending 2.5% of GDP on defence.

Ships, drones and helicopters – some more than 50 years old – will be decommissioned.

No replacement for the Watchkeeper drones has yet been announced. But drone technology has progressed quickly in the 14 years since it was introduced, the MOD said, something which has been particularly obvious during the Ukraine war.

And that was Watchkeeper, 2002 to 2024

Watchkeeper Description

Watchkeeper is a programme, not just a piece of equipment.

Thales and Elbit formed a joint venture called UAV Tactical Systems Ltd to produce and support Watchkeeper.

Systems and suppliers include;

- Thales; Lightweight, Multiband Airborne Radio (LMAR), a modified PRC6809 Multiband Inter/Intra Team Radio

- The Thales/Elbit joint venture, El-Op, provides the sensor payloads.

- Boeing and Cobham; sub-assemblies and components

- Cubic Corporation; Tactical Common Data Link, also provided through Ultra The system provides up to 11 Mb’s over a maximum range of 150 km in a package weighing no more than 4.5 kg

- Lola; airframe composites

- Elbit; air vehicle

- ABSL; Lithium-ion emergency power backup

- Logica CMG; digital battlespace integration

- Marshall Specialist Vehicle; ground station shelters and vehicles

- Altran Praxis; Safety engineering

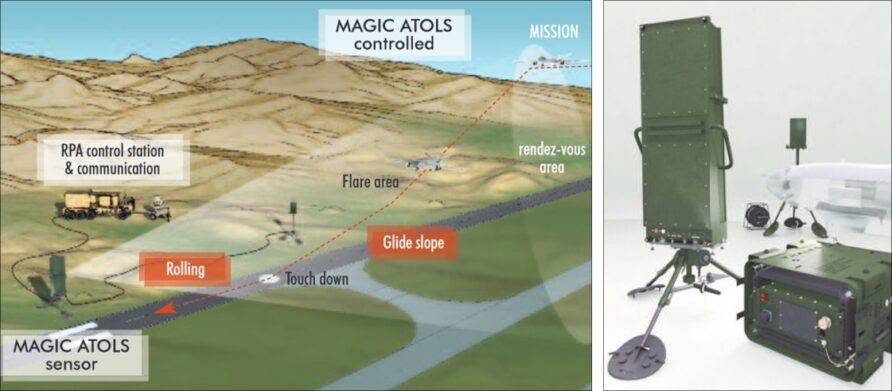

- Thales; MAGIC automated take-off and landing system

- QinetiQ; airworthiness consultancy and image data management

- Elbit/UAV Engines Ltd; UAV engine

- Vega and Mak Technologies; training

- Athena Technologies; Inertial navigation system

- Secure Systems and Technologies; TEMPEST R ruggedised computing and network equipment for the Ground Control System and image analysis.

The additions over Hermes 450 include ;

- Substantial redesign of the existing air vehicle to provide greater payload, structural integrity and ease of maintenance

- Enhancement of EO/IR sensor resolution

- Addition of a SAR/GMTI radar sensor

- Addition of a Laser designator/rangefinder

- Redesign of the undercarriage and arrestor wire to allow rough strip operations

- Landing lights

- Additional electrostatic discharge and lightning protection

- Addition of an Automatic Take-Off and Landing (ATOL) system

- Secure UK data link and communications infrastructure

- De-icing system for improved survivability and operating envelope

- Integral expeditionary and mobile capability

- Organic training facility

- UK airworthiness qualification and Release to Service for UK training

- The UK logistic infrastructure, manufacturing and repair facility

In broad terms, the Watchkeeper programme consists of;

- Air vehicles, each with an EO/IR/LSS and SAR/GMTI payload

- System integration

- Ground equipment

- Training System

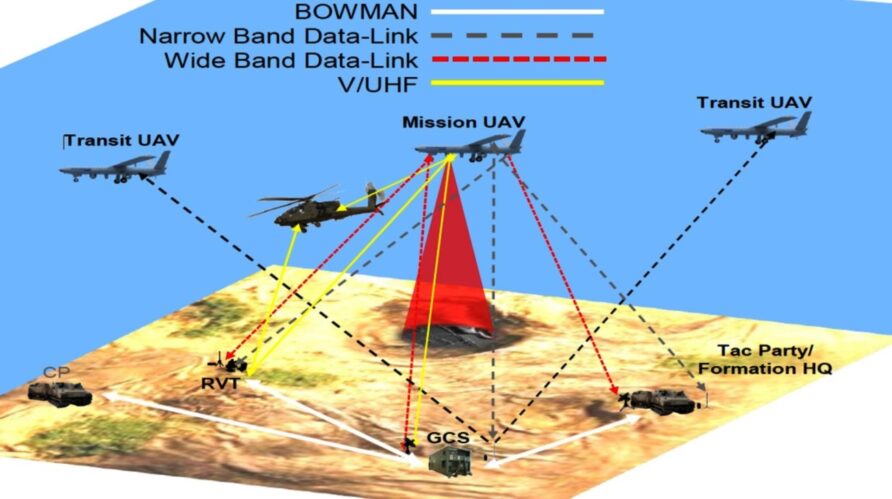

Concept of operations;

Air Vehicle and Payloads

The Watchkeeper air vehicle is a modified Elbit Hermes 450A, called the Hermes 450B. The total weight is approximately 500 kg, it has a maximum range of 115 km with an endurance of greater than 16 hours.

Whilst the Hermes 450 and Watchkeeper look the same, they are not the same, far from it. Differences in the undercarriage, wing root and the twin payloads are particularly noticeable, but there is more than just those,

Watchkeeper has growth potential to 650 kg and a much more robust airframe. Two particular features of importance are rough field landing and wing de-icing.

A take-off distance of 1,200m is needed.

The Dual Air vehicle Container is a particularly ingenious container for the disassembled air vehicle, two per container, but I guess you knew I was going to say that!

It has moved on somewhat, from the container shown here

Watchkeeper has two payloads, optical and radar.

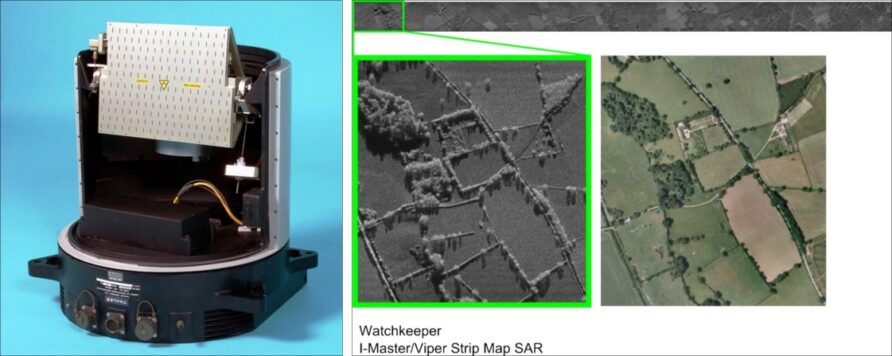

The 32Kg 620W Thales I-Master / Viper (Ku-band 12.5 to 18 GHz) synthetic aperture radar/ground moving target indicator (SAR/GMTI).was eventually selected for Watchkeeper.

I-Master was developed from the Racal POD SAR and includes technology from the Searchwater radar.

It can rotate through 360 degrees to operate up to 20 km in strip mode and 15 km in spot mode, able to detect slow-moving targets such as vehicles or people out to 20 km.

There are four GMTI operating modes (sector, 360 degrees, tracking, and spotlight) and two for SAR (strip and spotlight).

GMTI is extremely useful for change detection, showing patterns of life and tracks, for example, the same kind of capability as delivered by the RAF’s Reaper and Sentinel (and RN Crows Nest) systems.

I Master also has a number of new maritime modes.

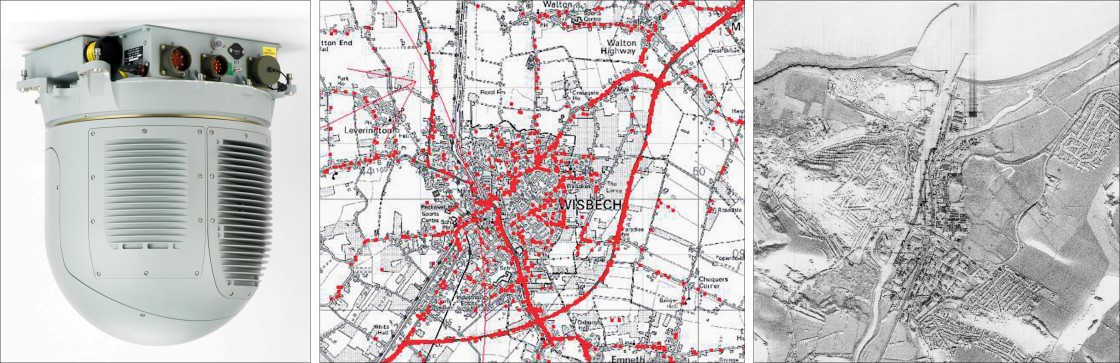

Working with the I-Master is a 38Kg El-op CoMPASS IV (compact multipurpose advanced stabilised system) electro-optic observation system that also includes a laser range finder and target designator.

From the product page

COMPASS IV can be configured with a variety of sensors to optimize your mission-specific objectives. Optional sensors include an eye-safe laser rangefinder, daylight TV, spotter scope, laser area illuminator, laser pointer, and diode pumped laser designator. A step-stare function allows the capture of full-frame digital stills, which are geo-registered at the pixel level and can be tiled for high-resolution area coverage

The Compass is mounted in the front position and the I-Master, the rear.

The dual sensor system is one of the most important features of Watchkeeper.

QinetiQ has also developed a communications intelligence (COMING) payload for Watchkeeper, click here for more details.

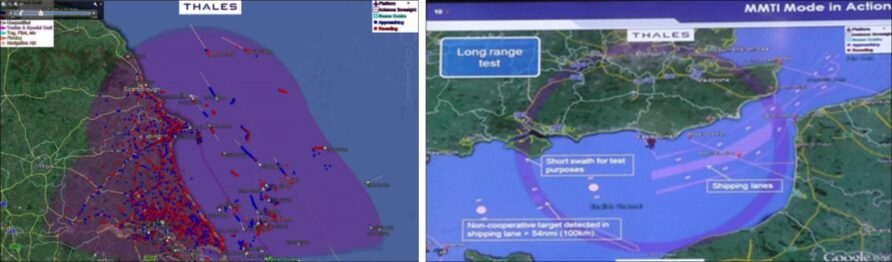

Maritime and Littoral

Although it was not in the original requirements, Watchkeeper has evolved such that it was trialled for maritime and littoral operations.

The Royal Navy’s ‘Unmanned Warrior’ exercise

The Thales Watchkeeper unmanned air system is set to play a key role in a major UK Royal Navy exercise later this year to understand how unmanned systems in the air and at sea might add real innovative operational capability in a military maritime environment. More than 50 vehicles, sensors, and systems from across defence and industry will be deployed in the Ministry of Defence Unmanned Warrior exercise in October. For the first time, Watchkeeper, currently in service with the British Army, will fly in a littoral naval environment operating alongside a warship and a merchant vessel. As an industry leader in autonomous and unmanned systems, Thales will be showcasing its capability through Watchkeeper, the Halcyon Unmanned Surface Vehicle and its collaborative work in the field of unmanned command and control research. Watchkeeper will be integrated into a series of exercises varying from persistent wide area surveillance support up to 150 kilometres offshore, to landing forces and naval gunfire support. The combination of Watchkeeper’s Electro-optical/infrared sensor and I-Master Radar make Watchkeeper optimised for both land and sea operations, and for tracking fast moving targets such as jet skis and small boats. Data collected by Watchkeeper will be streamed down remotely to the vessels and analysed by trained operators to make better-informed command decisions in support of the trials exercises

This has been enabled by continuous work by Thales on the i-Master SAR, specifically its ‘maritime modes’

MMTI allows users to detect and track targets on water: from small, fast-moving craft such as jet-skis; to larger, slower vessels such as ships and tankers, in all weather conditions, day and night. Algorithms designed specifically by Thales allow users to perform a range of tasks that include detecting unusual vessel movements, perform “pattern of life” analysis, and conduct persistent tracking of targeted vessels.

With MMTI mode, I-Master can now see the widest range of man-made movement, from an individual walking on the land to a ship sailing on the sea, and everything in between, using a single sensor.The new maritime mode is designed for customers seeking to monitor maritime borders and exclusive economic zones, protect strategic maritime assets, and track the movement of vessels not using the Marine Automatic Identification System

Cross-cueing of sensors has provided Watchkeeper with a valuable maritime surveillance capability.

Although Watchkeeper can technically land and take off within the flight deck restrictions of a Queen Elizabeth class aircraft carrier, no plans for this have been announced, with the Royal Navy exploring other systems.

Ground Equipment

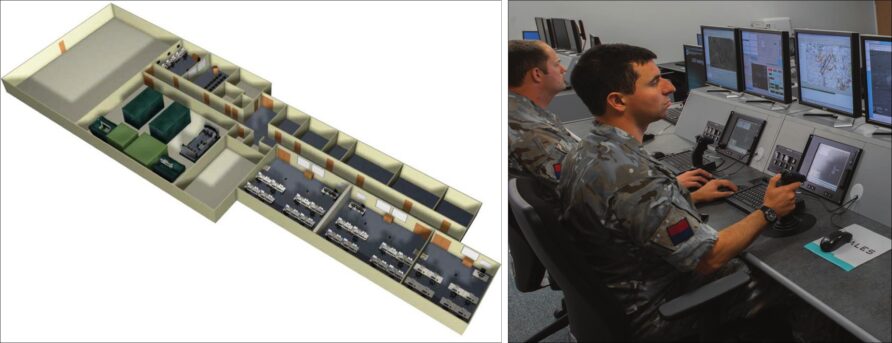

The Ground Controls Station is the primary mission planning and control location, able to operate connected to a wider network or as a standalone capability.

It is fully demountable and standard ISO container-sized.

Each GCS can control three air vehicles.

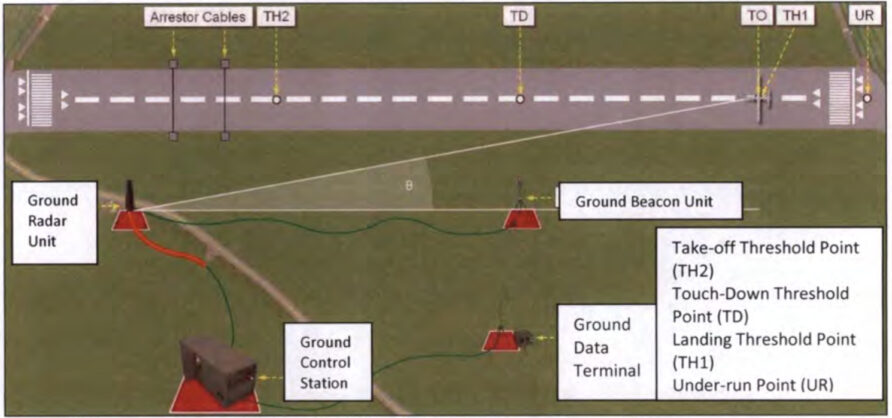

To improve safety and reliability during landing and take-off, an automated system is used, the Thales MAGIC ATO.

The Thales solution utilises an X-Band radar and beacon. In the image above, the large tripod-mounted object is the Ground Radar Unit (GRU) and the smaller device, the Ground Beacon Unit (GBU). A smaller beacon is also carried on the aircraft. The other object shown above is the Power Control Unit (PCU). Further information can be found here

Data link and arrestor cable systems complete the ground equipment

The system is transported on standard Army vehicles, a special to role Pinzgauer also used for air vehicle towing and other tasks called the Flight Line Command Support Unit (FLCSU).

Remote video terminals and tactical terminals complete the equipment set.

They are typically laid out as per the diagram below.

Training

Training is provided from a dedicated facility at Larkhill.

Ascension Island will also provide an alternative training location.

To finish, a couple of videos.

The first is a general corporate video.

And the second, a fantastic discussion on Watchkeeper and other UAS in the British Army from the fantastic Unconventional Soldier podcast.

Change Status

| Change Date | Change Record |

| 01/03/2017 | initial issue |

| 13/07/2021 | Update |

| 08/06/2024 | General update |

| 20/11/2024 | Watchkeeper withdrawal |

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I don’t claim to be a full expert, but isn’t Watchkeeper another piece of duplication/”too many cooks spoiling the broth?” What more can it add for joint force ISTAR when there are other manned (eg. Wildcat) and unmanned (Reaper/Protector) ISTAR options? Or does it help in large scale warfightig scenario.

TD, the CO of 47 RA says it will be under JHC command. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=783635515081477&id=299432630168437 RA is just the unit. I suppose in the future they can rename the unit as 47 AAC?

I have been around the Hermes for quite a few years, one thing to note is that it sounds like a lawnmower when the engine is turned on. A very loud lawnmower. Unless there has been a change to the engine from the 2 stroke Wankel, you can forget about the fables of “UAVs sneaking in”. Usually, anyone close by will be able to hear it. From what I have seen, the protocol for usage involves climbing the aircraft to a high altitude, turning the engine off and letting it glide silently past the target, not over it. Once they completed the pass, the operators will then turn the engine back on and return to a higher altitude.

If you are anywhere near the vicinity of the UAV when the engine is on, you’ll definitely know it is there. Just imagine a flying lawnmower. That is how it sounds like.

Are you likely to discuss a weaponised version of Watchkeeper for UK service? This is already being contemplated for Poland and the ME, and I understand that the RA is at least considering it.

It would seem like a useful capability for the UK to have, even if weapons use was limited to targets of opportunity. Would providing the additional training for pilots be a major stumbling block?

The thing to remember is that Watchkeeper’s primary role is making out battlefield artillary effective. As the Russians have recently demonstrated that is a critical capability. The more weapons you hang off Watchkeeper the less range and endurance it will have, compromosing its primary mission.

My guess is therefore that UK Watchkeeper won’t be weaponised. We have Reaper/Protector for that role which other countries do not.

PE is right. There is also the problem of capability creep. The old UAVs were conceptualized as cheap disposable units that you can lose without worrying about it while flooding the battlefield with sensors and maybe even suicide drones (e.g Harpy). With the stacking of all the capabilities, UAVs have gone beyond “cheap and plentiful” or even “disposable”. So the more capabilities you stack on it, like weapons, radar, IR/EO etc, the less disposable it becomes and the more you cannot afford to lose even a single one. There has to be a breaking point somewhere when it becomes more economical and survivable to simply send in a high speed recon fighter.

The end game for “Capability Creep” is presumably a stealthy Fast Jet UCAS with the ability to penetrate defended airspace without endangering a pilot.

Which is not to say we don’t also need something cheap and plentiful to spot the Artilliary and give a Brigade, Batallion, Company commander an eye in the sky.

In the case of France the Reaper drones are an important capability. Today we could not do without them, be it Iraq, Syria, and Africa. In Iraq and Syria, we do not use ours but almost no shot is performed without an identification validated by a drone to avoid collateral damage. In Africa, drones allow us to carry out many missions and contributed to the success we have achieved during special operations. With the drones, we arrive well enough to follow the terrorist groups and we were able to attack the many small ammunition depots and fuel they had constituted.

Very interesting article TD ,I never knew we had been running reconnaissance drones for so long.

Arming the Watchkeeper seems foolish to me as pointed out above will reduce it allready limited endurance. On a fast jet being used to penetrate contested airspace that’s the huge package the F35B will bring to the party replacing what we would and have tasked Tornadoes with Raptor pods with.

For Observer :-

http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=0rJnXZsrMjU

It is a surprise how far our unmanned aircraft go back. All largely unnoticed until the current generation in service.

The Royal Navy’s FDUAS program seems primarily concerned with a frigate deployable system.

The aircraft carriers should be capable of embarking conventional take off and landing UAVs a fair bit larger than the little Watchkeeper.

Greater range, payload, and power would probably be better in relation to aircraft carrier operations; but I could imagine that Watchkeeper might be a relatively low risk, low cost first step towards a more capable carrier-borne UAV.

HMAFR. Apache is now in JHC, but prior to JHC (late ’90s), Army Air Corps operated Lynx TOW came under Royal Artillery command along with all other Army missile systems. So there is no real reason why the RA unit operating Watchkeeper within JHC would have to be remade as an AAC unit.

I know there is a launch catapult option for Hermes/Watchkeeper. Is there one for Predator/Protector? Presumably a Ford Class EMALS would be capable of the job so maybe no-one has bothered to develop a smaller lighter option yet.

Ok so basically Watchkeeper is to help the artillery and MLRS batteries.

Then there’s Defender, Shadow, Reaper and other ISTAR manned and unmanned aircraft for other roles. One nice ISTAR family.

All these arguments against weaponising Watchkeeper sound sensible. However, aren’t they pretty much the arguments that were used when Reaper was first procured and used only as an ISTAR asset? Why wouldn’t the same progression towards an armed vehicle occur in this instance also?

Becasue of the unparalled, persistant and comparitively cheap killing power of ground based Artillary. Watchkeeper is weaponised: the weapons just sit on the ground ;)

The radius of operation and the 4000ft runway requirement makes me think that Watchkeeper is in a tough spot. If you have the airfield a Predator/Reaper or other large UAV would be a possibility with all it’s requisite advantages over Watchkeeper with a key one being weapons capability.

The Army would likely be better served by something along the lines of the Boeing Insitu Integrator which can be launched and recovered in the field, not to mention from ships at sea.

In the 70’s and 80’s the Midge (CL89) drone was operated by 94 Locating Regt based in Celle supporting BAOR and an independent unit 22 Locating Battery based in Larkhill supporting 3 Div and the AMF. During the 80’s 94 relocated to Larkhill and absorbed 22 bty to form one very large RA Regiment. Prior to the merger 22 Bty had over 150 personnel plus REME, ROAC and Int Corps and its own RSM even though it was only a battery.

So the UK army had 4 drone troops each with 2 Midge launchers.

The rule then was that to be operated by the Artillery it had to be launched off the back of a truck, anything else that required a runway was the AAC.

With the advent of Hermes 450 and Watchkeeper and the need for runways the responsibility for operating these types of UAV’s should either be the AAC or even a joint command involving the RAF.

We have three drones Reaper in 2015.

The basis of Niamey, where the drones are taking off that depart fly over the north of Mali and Niger in search of terrorists armed groups descendant of Libya, has three Reaper and two Euro-Israeli Harfang. Added to several Reaper of the US Army, which also provides us intelligence.

France, which has only two other Harfang, has made the acquisition of drones a priority to gain autonomy from its partners. In total, the military program law provides for the acquisition of twelve Reaper by 2019.

The Reaper depart for missions that can last up to 15 hours, therefore any longer than reconnaissance aircraft. They are also less rapid, 400 km/h at cruising speed for a operating range of 1850 kilometers.

In Niamey, drone crews follow the orders from Lyon (center-east of France), where the operations are directed.

A Rafale is built for performance, is a sprinter. A drone is a marathon runner. If we obtain heavier drones, we will equip maybe them with missiles.

If it is for destroy a target about the size of a car, I do not know. It is not in the habits of the French army.

Drones will penetrate the first on the theater of operation, transmit the information they collect.

In the case of Syria and Iraq the drones open the way of Rafale. Heavily armed and in charge of the attack on localized target by drones, this requires the use of cruise missiles with high capacity for destruction, that drones can not carry due to their size.

I just don’t understand the size of it and the need for a (even a rough) runway – it looks like at the size (deployed in a full ISO container) and range, should it not be an RAF asset ? Shouldn’t the RA have something more “tactical” ???

Wk is the 4th generation UAV in RA service since 1964 (MQ 57, Midge, Phoenix, Wk). The justification for the first three (at least) was to locate hostile batteries, and hence enable effective CB fire (counter-mortar was a different matter and the radars were fine). For this reason UAV control was the responsibility of the Divisional Arty Int Officer. The original reason was that the RAF was unable/unwilling to provide the necessary service. This had been the case with air recce in WW2 up to about mid 1942, but processes were sorted out, not least because the RAF recce wing (one per army) wasn’t too far away from the customers and it was possible to attach an arty int team to recce wing HQ (plus some RE surveyors to do accurate fixation).

NATO deployment introduced a heap of complexity, not least the distance from the clutch airfields to the Weserberg region, not to mention no guarantee of a timely, available service by 2 ATAF. Given the size of the Soviet artillery arm to call this a concern is a gross understatement (although modern radio link sound ranging was a help). Of course it was a bit academic until 1965ish when the 175mm M107s entered service.

The idea that UAVs were introduced as a general air recce resource is, to put it mildly, fiction. Of course no-one took too much notice until Phoenix arrived with its capability to deliver real-time imagery, then everybody started wanting it.

There also has to be a bit of care and knowledge as to where the information flows and what units the UAVs are attached to. Most people have the wrong idea that UAV data goes to the man in the field. This isn’t true as the “common soldier” will probably never see the take from the higher end UAVs. They will *not* get data from Watchkeeper or Predators, those go way higher in the foodchain to a brigade or division HQ or higher for strategic planning. Depending on where the UAV is attached to and how the data flows, it looks like each individual “arm” is having their own UAV system for their own needs, Desert Hawk for the armoured/mechanized platoon level, Watchkeeper for RA batteries and Predator and HALEs for HQ level and above. Hence all the “duplicate” systems.

Concerning the drones we are seriously overdue compared to the UK. On our side it is expected that the program of observation and surveillance drones Reaper will take ultimately optical or electromagnetic French or European sensors. Twelve mid-altitude drones are planned for 2019, the sale could go up to 16 drones at the term. The next generation of these drones will be prepared by privileging European cooperation.

The Neuron developed over many years by Dassault Aviation and the DGA is still far from being operational. But in the war of the future dreamed by our engineers of armament, we’ll see the Neuron drone sent as a scout to open the way for combat aircraft. They will include a mission to locate and destroy air defense systems, and thus enable to Rafale to hit strategic targets without risking the lives of their fighter pilots. It would appear that we will develop the Taranis with Neuron, I am waiting to see this.

Concerning tactical drones, probably Watchkeepers will be acquired for around fifteen units by 2019, on the thirty planned for this model.

For the moment the French doctrine always banishes the use of drones killers. Killing someone to 3 000 km poses ethical problems. France is still in agreement with the Council of Europe, which opposes targeted killings carried out by drones.

Objecting to targeted killings by drones is political stupidity at its best. Particularly when many nations opposed to it have arsenals that include cruise missiles with ranges of many hundreds of miles. It is an entirely artificial distinction meant to make someone feel good about something. People are just as dead if a drone drops a bomb as they are if a fighter does it.

I think the biggest obstacle to UCAV use isn’t any moralistic nonsense. If they work efficiently they will be used when the time comes. I personally don’t think they will work anytime soon to the degree they are worth the trouble.

I agree, a war is always dirty, during a war there are always people killed. But as long as this does not pass on TV it does not matter. During the intervention in Mali the French army killed 700 jihadists, on French television I have not seen a death, I only seen a leg that soldiers had forgotten to remove.

Given the 150km radius of operation, a 150km likely sensor horizon, and the 1200m takeoff distance I don’t quite see the point. It doesn’t seem to fit any particular niche. Either you have an airstrip (in which case use Reaper) or not (in which case use a copter, or Reaper from another airfield).

What is the likelihood of a 1200m strip being knocked up JUST to launch Watchkeeper from?

@Simon,

I thought that the take-off distance was 280 meters ? By against, I believe that it requires a arresting gear to the landing, so on a landing strip. Otherwise, in the case of France we have no choice, only alternative to Watchkeeper is Sagem’s Patroller which weighs nearly one tonne and is therefore closer to a Reaper than a tactical UAV, and then the Lancaster House Treaties commits us to cooperate, we are friends :)

Quite the endurance at range for the size of vehicle. Given the I-Master you could easily keep an eye on shipping in the Lebanon/Syrian coastal area from Akrotiri. Even without the auxiliary tanks.

With regards duplication: Never be afraid of having crossover and/or complementary capability.

On the topic of weaponisation, last official word (2010, standfast more recent financial underwriting of Polish/MBDA development) is that it was desirable but not essential. Given we’re more likely to see these vehicles operating in sovereign airspace assisting with flood evaluation and recovery as we are to see them tracking Russian supplies to Tartus, it’s a difficult sell with “Protector” receiving significant funding of late.

A little surprised we’ve not seen them deployed to Akrotiri to keep an eye on refugee traffic, or are the operational numbers still assisting in Afghanistan?

In days of yore army UAVs were tasked by setting specific questions about specific places, the flight path was planned to look and these and take the happy snaps (a tad limited with Midge which could only cope with a few direction changes per flight), after recovery the film was processed and the image analysts who were part of the Midge troop would do their stuff and report the answers. Obviously this arrangement will more or less continue but realtime imagery and flight control open things up a lot, eg allowing investigation if something looks significant as well as more speculative tasking.

Realtime imagery offers other options as well, whereas Phoenix didn’t really exploit this Watchkeeper will because the organisation includes elements that can be attached to any HQ to provide imagery to them in realtime. It may be further helped by increased trunk comms bandwidth.

Desert Hawk is deployed with a small (c.3 pers) detachment, normally a det is deployed with a Cbt Team (ie coy/sqn). This means if the coy/sqn OC wants to see the imagery he/she will be able to, I assume imagery can be recorded to some extent and I can envisage circumstances when the OC will want to show it to his O Group.

In the context of WK the key letter in ‘TUAS’ is the S, i.e., it is a System, not just a couple of chaps in a shed flying a small aircraft with a camera on it. The operators don’t have to be pilots.

Interesting that Queen Bee is mentioned. This, anecdotally, is the apiological origin of the word “drone” to refer to unmanned aircraft. Nothing to do with the noise they make. The BBC in particular always refer to ‘drones’ and it makes me squirm every time I hear it…