To end this long series of posts, some discussion points on helicopter transportable vehicles and equipment.

Can the British Army and Royal Marines Align?

Who would use these types of vehicles and equipment?

Joking aside, the likely user group will include the Royal Marines, 16 Air Assault Brigade, Special Forces, and the Army Special Operations Brigade.

Wherever possible, this group should actively seek opportunities to exploit common requirements with common equipment, but commonality for its own sake should not be pursued.

Both helicopters can operate from ships (although Merlin is much better in this), and both helicopters can be used by any group, but the likelihood is that the Royal Marines will use Merlin more than Chinook, and the Army, the inverse.

Apart from this, requirements may diverge to a point where commonality works against objectives.

Army users may see A400M/C17 density and heavier stores as more important than being able to operate from a Littoral Strike Ship or aircraft carrier.

Whether accidentally or design, most user groups seem to be moving to twelve-person teams.

Sustaining those teams for 12 days at 200 nautical miles from the ship or operating base is another relevant and common goal

Aggregating these teams, six per squadron/company, with three squadron/companies per battle group, joined by support and HQ squadron/company generates a battle group of approximately 350 to 400 personnel, depending on how heavy the support and HQ function is. These can be rotated at readiness, and sustainable.

Organisational design tends to surface opportunities for commonality, so despite each user group having their requirements and some existing programme momentum, we may end up with equipment that can be used by all.

I live in hope.

The Magic Number, Beyond 1.6m Wide

As you push out beyond 1.6m wide for a single vehicle, two things happen.

First; Loading and unloading becomes slower, this exposes the helicopter when it is on the ground and means those doing the loading and unloading might find it difficult to exit the vehicle safely. Tie-down also becomes more challenging, everything just gets harder and slower, less operable.

Second; Vehicles become dangerously close (from a budget and programme perspective) to general utility types. If we are replacing Land Rover with a pickup-derived design, and they are about 1.8m wide, what role do specialist vehicles at the same width have? Can we justify a vehicle with such a niche role when it is within inches (literally) of the vehicle that will be purchased by the thousand?

I can see the Royal Marine’s rationale for purchasing MRZR, it neatly avoids those two pitfalls.

This is why I don’t think there is much mileage in pursuing vehicles unless they are part of a wider programme, e.g. Land Rover replacement, unless they have unique qualities such as very high levels of mobility, are narrow at the hips, or have specialist roles like towing a GMLRS trailer.

The more a vehicle looks like a future Land Rover replacement, the less justification it has to draw on the scarce defence budget.

Risk Acceptance

How much risk is defence willing to accept?

In an age of armed FPVs, guided missiles and pervasive surveillance, is it acceptable to bring into service vehicles without active or passive protection?

One of the obvious trade-offs forced by small size and lower weights is that the majority of vehicles described are without any means of armour, active defensive systems, or even ECM.

Small size, terrain accessibility, speed, and low signatures also contribute to protection, but this only goes so far and there has to be acknowledgement of the elevated risk compared to the extremes of CR3 and Mastiff.

Not getting into fights with enemy vehicles on their turf is also the greatest contribution to vehicle and crew safety, this is why I don’t like the idea of mounting automatic weapons on them.

I tend to see these vehicles purely as transport, not fighting or patrol vehicles, bereft of armour and armaments, the people they carry are what makes a difference.

Risk acceptable is also a factor in specific aspects of vehicle design and selection, seating especially.

It might seem like a philosophical question, but we have to decide what a seat is!

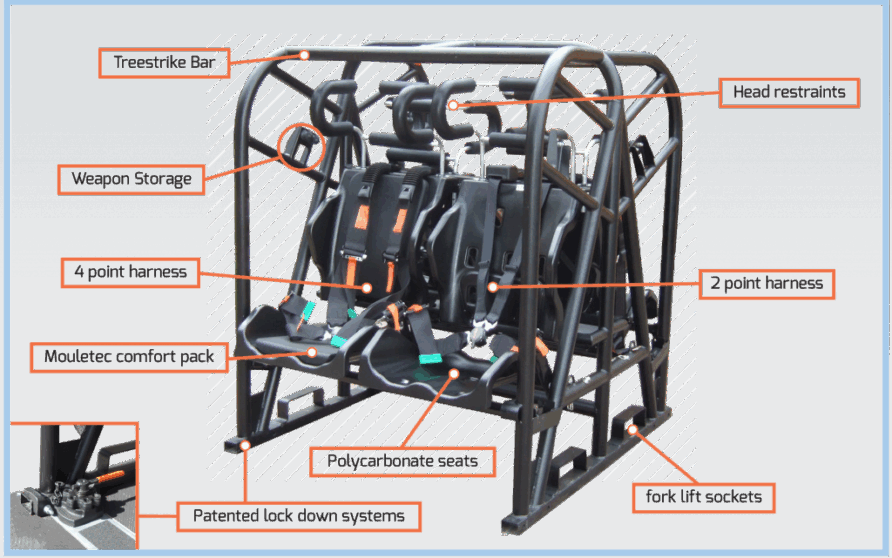

These are seats.

And so are these

Many of the vehicles in the previous posts make use of bench seating with simple lap belts, and these may be perfectly acceptable at low speeds and in a civilian context, but are they acceptable for a standards-compliant military vehicle? #

This matters a lot when you are dealing with dimensional constraints and trying to maximise seating density, and that is before we even get into the subject of passenger-carrying trailers.

I do not comment either way, except to observe that density and carriage will be higher with simple seating and lap belts than with three-point harnesses, crashworthy seating and fixed rollover protection.

UK Industrial Matters

Generally, I am always going to favour British industry, and I make no apologies for this.

Many of the vehicles we seem to be looking at are at the end of US, Canadian and German supply chains.

I get the process that drives this, and I get that the large defence primes will always have an advantage, but if the Land Industrial Strategy is more than just words, I simply do not accept the logic of paying German or US primes to develop Canadian vehicles when we have UK SMEs like AVT, DCE, and Supacat.

The ‘process’ might be a valid reason, but it is not an acceptable excuse, and we need to do better with hard-earned public funds.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

The Massive Potential of UGVs

RANG-R is not a civilian vehicle conversion, it has been designed from the outset with defence users in mind.

It is well protected and resilient, and scaled for a range of payloads that go way beyond basic load carriage such as EOD and route clearance, including those that need hydraulics.

Viking is also designed from the ground up, and they both have a flat load bed that is suited to adaptability for carrying sensor and weapon payloads.

RANG-R can also have additional ballistic and mine protection added, and both Viking and RANG-R have potentially shorter supply chains and higher UK industrial participation than others.

They both have utility across 1 DIV and 3 DIV and, with some coordination, across the Royal Marines and other users.

I am less convinced of their value for a simple platoon or team load carrying, their payload-to-kerb weight ratio tends to be lower and adds a lot of cost and complexity to what can be delivered with simple and low-cost crewed vehicles.

Where they have massive potential is exactly this scenario, not having any personnel on the ground involved at all.

Scenario 1

Four Merlin helicopters fly from the deck of a Future Littoral Strike Ship over the horizon to a remote location. After landing, they disembark four IDV Vikings, each with a Trakkon RWS, 30 mm AEI Venom cannon. A small team conducts checks and arms the cannon, returning to the Strike Ship with the helicopters.

The vehicles move silently to their final locations out of earshot and radar detection of the helicopter landing site, some 100 km away.

Three taking up positions 2 km away, overlooking a road choke point, they go into overwatch mode, waiting for a ground-launched ballistic missile convoy that intelligence sources had indicated would pass by in the next 48 hours.

The other exploits the terrain to avoid detection and remains as a reserve.

When the convoy does arrive, putting it simply, it gets detected and brassed up by three 30 mm cannons, and that was that for the convoy.

Scenario 2

A second scenario sees four Chinook take off from a forward operating base, each loaded with Aardvark RANG-R UGVs. Their mission is to prepare a helicopter landing site near an open-cast coal mine for a multinational air mobile force arriving within 48 hours.

Landing on an access road some 20 km away, the first Chinook has three RANG-R with surface clearance blades and manipulator arms. Upon leaving the aircraft, they move to mine and begin clearing obstacles and unexploded ordnance left over from a recent conflict.

The second and third Chinook each have two RANG-R, each carrying two 1,000L IBC containers of pre-diluted Envirotec ‘Rhino Snot’ dust stabilisation solution and a spray head. They arrive at the cleared site and begin spraying the area, in preparation for the landing force.

The last of the four Chinooks has two RANG-R, one equipped with a tethered UAS and the other a C-UAS package of radar and a 30 mm automatic cannon. The tethered UAS deploys and relays situational awareness information to HQ whilst the Rhino Snot is curing, the C-UAS provides overwatch.

Two days later, the advance force arrives.

Both of these scenarios might take a few leaps of technology readiness, but hopefully, you can see the potential, and potential can be enhanced by making sure any future UGVs fit perfectly within our two support helicopters.

The Long Arm of GMLRS*

*Other missiles are available

We have mostly discussed how for small teams we can extend the length of their legs, and in the weapons sections, I touched on extending the length of their clenched fists.

Without discounting the effects that small teams can bring to bear, giving that same team access to longer-range weapons brings them into the ‘strategically important’ category.

If I were the Royal Marines or Parachute Regiment, always under threat of disbandment or reduction, I would be thinking beyond being the best light infantry raiding and rapid response forces.

The table below provides an approximate comparison.

| System | Range (km) | 5 km symbols |

| Javelin, 81mm mortar | 5 | I |

| 120 mm Mortar — Guided | 5 | I |

| 120 mm Mortar — Guided | 10 | II |

| 105 mm Light Gun | 10 | II |

| 105mm Light Gun | 20 | IIII |

| Spike NLOS/Exactor | 30 | IIIIII |

| Hero 120 Loitering Munition | 40 | IIIIIIII |

| GMLRS | 70 | IIIIIIIIIIIIII |

| Land Precision Strike | 80 | IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII |

| ER-GMLRS | 150 | IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII |

| Naval Strike Missile | 190 | IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII |

| Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) | 500 | IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII |

Whilst RM-centric, this paper from RUSI makes the case for longer-range weapons.

Integration challenges should not be underestimated, but at least physically, there are no reasons why a trailer-based single missile or pod launcher cannot be developed that makes use of in-service complex weapons, or that we plan to bring into service.

Even with shorter-range systems such as Javelin, Brimstone and Exactor, a small team could deliver a disproportionate effect, especially when using non-line-of-sight weapons, an anti-armour blocking force for example (shades of 24 Airmobile).

Could we Stretch to Air Mobile Cavalry?

Apart from the Flyer and RANG-R, not one of the vehicles described in the series has any protection.

Apart from the UGVs, none of them has any kind of mounted direct-fire weapons either.

This is a good thing.

It discourages them from being considered fighting or patrol vehicles, just a means of moving people and things from A to B.

A question arises, can we stretch resources to build a genuine airmobile cavalry force to do cavalry things?

There are few vehicle choices, perhaps only one or two.

Although no longer in production, it is still worth highlighting that some Wiesel variants could fit inside a Chinook.

Not an easy fit, but the RAF has done it with Chinook.

Depending on the model, Wiesel 2 (with the extra road wheel) would also fit.

Its replacement, the Luftbeweglichen Waffenträger (Airmobile Weapon Carrier) or LuWa, is in the early concept and evaluation stage.

One potential contender, from ACS, Valhalla and FFG, is an interesting-looking vehicle.

LuWa is being designed for the CH-53 successor in German service, the Chinook, with kneeling suspension that brings height down to 1.85m.

So if we wanted to generate an airmobile cavalry force, a joint development with Germany would offer a path

One to consider.

Won’t Someone Think of Sustainment

To illustrate my point, that 1m square pallet below has a total of nine NLAW, a few minutes work for a 12-person raiding team.

The publicly released imagery of current vehicles tends toward the fighting element, it is public relations after all.

Pallets of ammunition, stretchers, and jerrycans of water and fuel aren’t that photogenic, so rarely get a look in.

Everyone knows they cannot be ignored.

But I would ask a question, does that knowledge of the actual payloads required to sustain even small teams translate into requirements?

Perhaps rotary or fixed-wing UAS will help ameliorate the problem, or air despatch from fixed-wing aircraft, but even the heavy lift UAS being demonstrated below only has a maximum range of 70 km and a maximum payload of 70 kg. They can do multiple round trips or work in parallel with others but round trip delay and detectability mean that they might be the total solution.

Perhaps more important than simple stores weight is stores volume.

Modern communication equipment, sensors, UAS, defence stores, and other equipment are carried in the ubiquitous Peli, Zarges, and Amazon cases.

Complex weapons come in special to contents containers that add weight and bulk to the datasheet weights.

As you can probably imagine, I think we should focus on carried weights and load bed size a little more in vehicle selection.

Terrain Accessibility is not a dirty word

OK, it’s two words!

One of the issues I can see with existing approaches is mobility, especially in snow and poor soils, the kind of terrain found in the High North and other areas.

It is not beyond the realms of fantasy that future operations may be conducted in the High North and or areas of deep snow, Muskeg/Taiga and lots of mud.

Extreme mobility requirements would tend to swing selection to tracks or multi-axle skid steers, but none of the current discussion on this subject seems to take note of such higher mobility requirements, focusing on speed on well-found tracks and dry ground.

This is not a criticism but an observation.

If the Royal Marines want to maintain one of their unique selling points, littoral manoeuvre, they should be looking beyond MRZR and into small hovercraft, inflatable landing craft, over-snow and high mobility vehicles that not only allow them to exploit their Merlin helicopter fleet, but also move across ice, estuaries, snow, tidal zones, and soft ground up north.

The same observation applies to the 16 Air Assault Brigade, although perhaps less of the littoral, but still an observation about mobility, especially given the likely lack of organic mobility support.

There is more to life than helicopters

Although this series is about helicopter internal carriage and the primary constraining of internal dimensions, other factors might be considered.

One of the key UK requirements for the A400M was that it could accept three Land Rover Defender 110s with trailers two abreast.

The 110 Defender is a shade under 1.8m wide.

If you are 16 Air Assault Brigade, this is important, it is especially important if you are in the market for a Defender replacement. It is vitally important that any Defender replacement, like the Babcock GLV (and others), is less than 1.8m wide because not only does it allow for Chinook internal carriage, it allows a dense load in an A400M.

A400M dimensional optimisation is particularly important given it will be (when availability is sorted) the primary aircraft for moving 16AAB and an Air Manoeuvre Task Force.

463L pallet and C-17 compatibility will also be part of the decision matrix for the Army but perhaps less so for the Royal Marines.

Driving licences and training demand are always a consideration, roadworthiness and fuel usage, perhaps even the 2m ramp width and six-tonne payload of a Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) Mk5, 5.8m length and 2.34m width of a 20ft (6.1 m) ISO container, the 4.9m length of a two module ATAX air despatch platform, or even the internal dimensions of a ULD container than can go in a Voyager lower deck hold.

Perhaps even being able to fit a vehicle on a VRA rack might be considered important for deployability.

This is the kind of thing that makes finding dimensional compatibility for a globally deployable force so complicated.

Existing Programmes and Current Choices

Some existing programmes bisect any notional requirement for helicopter transportable vehicles.

The Royal Marines have been trying several options in the last few years, from the Polaris Dagor to the three-axle Quad ATV, and more recently, seem to have settled on the Polaris MRZR as a baseline, with a handful of Path A remote and autonomous kits thrown in.

The British Army is looking at options via a Pre Qualification Questionnaire (PQQ) for the Low Technology Mobility Platform (LTMP) Medium and Low Technology Mobility Platform (LTMP) Light requirements so it seems despite continuing to live in the hope that a joint requirement might emerge, that seems off the cards.

A bit more detail here

There are various programmes investigating options for remote and autonomous vehicles, and not just the higher profile ones like robotic platoon vehicles, the various spirals exploring weapons and sensors, ‘mind the gap’ and CBRN recce projects, and last mile resupply.

Collectively, there is a lot of investment and research effort going into UGVs/

Even Future Medium Helicopter may have some requirements for small vehicle underslung loads.

Standouts and the Road Less Travelled

Vehicles like the Polaris MRZR are simple to specify, or even build requirements around (for example, the LTMP specifies quite a low payload that looks suspiciously like the MRZR) because they exist in an existing ecosystem and user base of NATO users.

If the US has purchased a vehicle already, it is much easier to purchase than go through the cost and effort to ensure compliance, especially if a UK SME or organisation unfamiliar with defence is involved.

Those SMEs might also make a judgement that the return is not worth the cost and time to try to contract with the MoD, it is notoriously difficult to deal with.

We can rightly complain about this state of affairs, but defence users have to live within a set of processes not of their making.

Being compliant with various DEFSTANs and having military user requirements comes at a cost, simply comparing an MRZR cost at £40-75k versus any of the civilian UTV models shown in the previous posts at £15-25k demonstrates the differences.

We might joke about the cost of a tin of green paint, but it is more than that, defence has to be inquisitive about the cost differentials, and about accepting design and capability compromise.

The path of least resistance might mean limited choices, but it also results in vehicles entering service.

That said, a handful of vehicles did stand out.

Rokon motorcycles

Not just because of their ruggedness and terrain accessibility, but also because of their towing and load-carrying capacities. I also particularly like the quick attach sidecar. It is easy to dismiss this but working across the space and payload constraints, the combination is actually near the top for space efficiency.

I don’t doubt very few will agree, but the numbers don’t lie, although the basic numbers are not the only thing that matters.

Fresia F-18

Not sure what much I can say about this, how about a slower two-seat quad with enormous carrying and towing capacity, hydraulic export, and two-wheeled steering.

its size makes it particularly efficient for carriage in small spaces.

Bale Defence RTV from Australia

Performance is excellent, and it seems a very well-considered design, but it is only available in a 2-seat version, which, oddly, makes it less efficient for filling the finite space of a helicopter. And this brings me to the fourth standout.

Polaris MRZR Alpha

The Alpha series is a genuine improvement over the standard MRZR and is also available in a four-seat version. They fill the space and provide considerably better personnel and load carriage, given a limited number of helicopters. If the Royal Marines were looking for an upgrade, they could do a lot worse.

Goldoni and Carron agricultural carriers

Chugging along and 30kph in what is a glorified tractor might not appear to be an act of war, but as with the Rokon, the numbers don’t lie. If we are interested in load bed space for bulky stores, and payload capacity for heavy loads, nothing genuinely comes close.

It would take a brave defence organisation to buy a few and try them out, but maybe trying them with realistic loads might wipe the smile off the naysayer’s faces?

Alpina Sherpa

For deep snow and towing sleds, whilst carrying five people, it seems ideal. If we could accept people carrying trailers/sleds, this would provide an excellent means of moving personnel over significant distances.

Aardvark RANG-R

Due to its dimensions and carrying/towing capacities, together with having a hybrid power pack and clear flat top, it has excellent potential.

Add in the protection against small arms, mines and fragmentation, and the ability to use hydraulic attachments, it looks excellent.

For the life of me, I cannot see why the Army is not all over this vehicle like a rash, oh, it’s British, understand now.

AVT Minerva

Its load-carrying and towing capacity, general modernity, hydraulics, and excellent amphibious capability characterise it as a successor to the still-mighty Supacat ATMP.

MTT-154

Read about it to see why, and then imagine how high you can stack them.

Final Thoughts

There are no ‘best vehicles’, merely an endless procession of trade-offs and compromises that always point to ‘what do you want to do’ arguments.

There is potential to do more, and spend more, but despite their relatively low numbers and small costs they would still have to compete with other defence needs in a world of finite budgets.

Expanding capabilities and adding value seems to me to be fundamental to the continued existence of their likely users, and these might be one of many tools they could use to do that.

And I know you all want one of those folding mini scooters.

See you in the comments.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

An interesting vehicle that looks like a lot of fun by maybe difficult to adapt to military use is the Russian Sherp. Full amphibious, genuinely all terrain and can carry 1ton load.

Excellent and very thorough update!

Great Article.

There has recently been a tweet about Royal Marines doing a course on using ponies for load carrying.

Thinking outside the box here.

Thanks, TD!

if with the same attention as Wiesel, whether CVR(T) could get a second life as an air mobility focussed vehicle. It is compatible dimensionally with Chinook internal carriage, just? Perhaps there is zero life left in them, but still a food for thought

The other thing that might also be in the margins for this topic is that the Bundeswehr got offered a 50% up-powered Chinook as their CH53 replacement; don’t know if anything came of that (and our 16 new are differently specced)

“The contract was worth £3.3m but only 15 vehicles entered service and have all since been disposed of.”

The number of times I see this! No wonder the British Army/MoD is broke and still having kit shortages and personnel still have to cope with a “make do” attitude.

TD, I think you missed the one interesting point on heliborne motor vehicles.

Helicopter-mobile vehicles were mostly a dud for the tasks that you seem to think about. Motor vehicles were already moved by cargo gliders in WW2 and were no game changer in airborne ops.

There was AFAIK one significant success for vertical heliborne envelopment in Ogaden during the 70’s, but its effects would have been feasible with a simple overland convoy as well.

Helicopter-carrier motor vehicles are hugely promising in alpine/mountain warfare. That’s a niche that they could actually shine in. All the flatlands air mechanization dreams have in my opinion proven to be

AND

That’s how it played out in Germany: Sci-Fi air mechanization concepts that were obviously impractical (while inspired by that forward helo base in ODS) were dropped almost immediately once the funding for army NH90 and Tiger helicopters was secured.

Hey TD, missing you on Twitter. Hope you’re still alive.

Really great article – possible notable absences are Polaris MZRZ D4 and Textron M5 Ripsaw? Also Supacat LRV might have been worth a mention? I know you can’t cover every vehicle but was surprised these weren’t really brought up. A Ripsaw formation could provide a very powerful & disruptive force?

Nice update.

The Janes correspondent asking at about 5:16 as to any of the GM Colorado left in the the squad vehicle,

in the vid,

the answer is an amazing… 70% of the components!

Great series :-)

If there's one thing missing it's the parachute option. Even if you don't want to invade Belgium by parachute, sustaining a force via fixed wing parachute support allows much higher throughput than relying on helis alone and so it's something worth considering. Of course, this then has further considerations for the vehicles and stores, but having helicopter requirements as a filter, you can rapidly figure out what vehicles really won't work as opposed to those that will, and preserve the CVR(T) ability to move overland over poor terrain, be parachuted, and then move by Chinook. In whatever order suits :-)

You lightly touch on the obsession with speed. The US Infantry Squad Vehicle had a significant requirement for speed. Maybe great for the desert but not very practical anywhere with ditches, tree and fence lines, hedgerows, and cultivated land. The reason the US feels the need for the ISV is they don't feel they can fly directly to/drop on the objective. So why do they think they can land at an offset and drive down the road at 50mph to the objective. Must be based on visions of the SAS in the western desert.