Excessive weights carried by infantry soldiers impact physical and mental agility whilst dramatically increasing injury rates. Although the problem is an old one, we should tackle it with renewed vigour

Share on twitter Twitter Share on facebook Facebook Share on linkedin LinkedIn Share on reddit Reddit Share on print PrintSince there were first soldiers the weight they have carried has been subject to cyclical variation and much discussion. The upward trend that saw its zenith during operations in Afghanistan is now subject to a realisation that it is both unsustainable and undesirable.

The Recurring Problem of Overburdened Soldiers

The problem is not new.

In ancient Greece, Iphicrates recognised the disadvantage of overburdened soldiers and introduced the concept of an organised light force called Peltasts that emphasised mobility and firepower over protection to overcome the much heavier armed and armoured Spartans at the Battle of Lechaeum. During the Thirty Years War, Gustav Adolphus of Sweden (often called the Father of Modern Warfare) favoured the use of combined arms where mobility was emphasised.

During the many reforms after the Crimean War, weight on the soldier was studied in detail. The 1865 ‘Report of the committee appointed to inquire into the effect on the health of the present system of carrying the accoutrements, ammunition, and kit of infantry soldiers, and drill &c. of recruits.’ was followed up with a second report in 1868 titled ‘The Second report of the committee appointed to inquire into the effect of the present system of accoutrements and knapsacks on the health of the infantry soldier.”

A third report is available here, its introduction had an excellent summary of the problem;

The soldier must be well fed: he is. The soldier must be well clothed: he is. The soldier must be well trained: he is. The soldier must transport a reasonable amount of equipment and personal belongings, but there is a limit to his performing the dual role of beast of burden and fighting soldier

It also warned against believing mythical tales of long road marches carrying extraordinary loads, from Romans Legionaries to British soldiers in the Peninsular War, myths were debunked with facts and solid conclusions drawn using scientific methods.

The report concluded that the ‘fighting value of a soldier is in inverse proportion to load he carries’.

With improvements in load carrying (packs and pouches), the maximum recommended load for marching was approximately 27kg. Work continued on both reducing the load, tailoring those loads to the application and determining the best means of carrying loads.

The Boer War reinforced lessons about infantry loads, an 1899 extract from a CO’s reports stated;

As regards the kit a man should actually carry, my opinions are entirely derived from regimental experience as a company officer in three campaigns in India and as a Commanding Officer in this campaign. I am strongly of opinion that the less weight we put on our men’s backs the better results we shall get, and for two reasons:-

I believe that other things being equal in actual battle, the lighter equipped of two combatants, and the least encumbered by extraneous articles, will win the day; he is, at any rate, the best adapted to take cover or to get rapidly across an exposed zone.

I do not consider our men are naturally good marchers; British troops have never had that reputation, but with strict marching discipline they can be taught to march well, and the lighter they are equipped the easier it is to teach them. I have frequently heard the argument adduced that foreign soldiers carry “so much” therefore we must train our men to carry a like amount. I do not believe that many of the overloaded soldiers could fight a modern battle without throwing away a portion of their equipment.’

Reductions swiftly followed but by the start of WWI, fighting weights carried had risen back up to 26kg, in sharp contrast to the 27kg maximum recommended for marching previously.

Fighting weights were by now the same as previous marching weights.

Despite some action to reduce this, trench warfare meant an increasing need to carry hand grenades, gas masks and cold-weather clothing. By the end of the war, the average carried weights were approximately 30kg. Reports noted again and again that infantry soldiers were so encumbered they were only able to close with the enemy by virtue of supporting fire and one even attributed some of the failure of the Dardanelles campaign to over-encumbered soldiers.

During WWII, the same problems occurred.

In the initial assault waves at Omaha Beachhead, there were companies whose men started ashore, each with four cartons of cigarettes in his pack—as if the object of the operation was trading with the French. Some never made the shore because of the cigarettes. They dropped into deep holes during the wade-in or fell into the tide nicked by a bullet. Then they soaked up so much weight they could not rise again. They drowned. Some were carried out to sea but the great number were cast up on the beach. It impressed the survivors unforgettably—that line of dead men along the sand, many of whom had received but trifling wounds. . . . No one can say with authority whether more men died directly from enemy fire than perished because of the excess weight that made them easy victims of the water. . . . This almost cost us the beachhead. Since it is the same kind of mistake that armies and their commanders have been making for centuries, there is every reason to believe it will happen again.

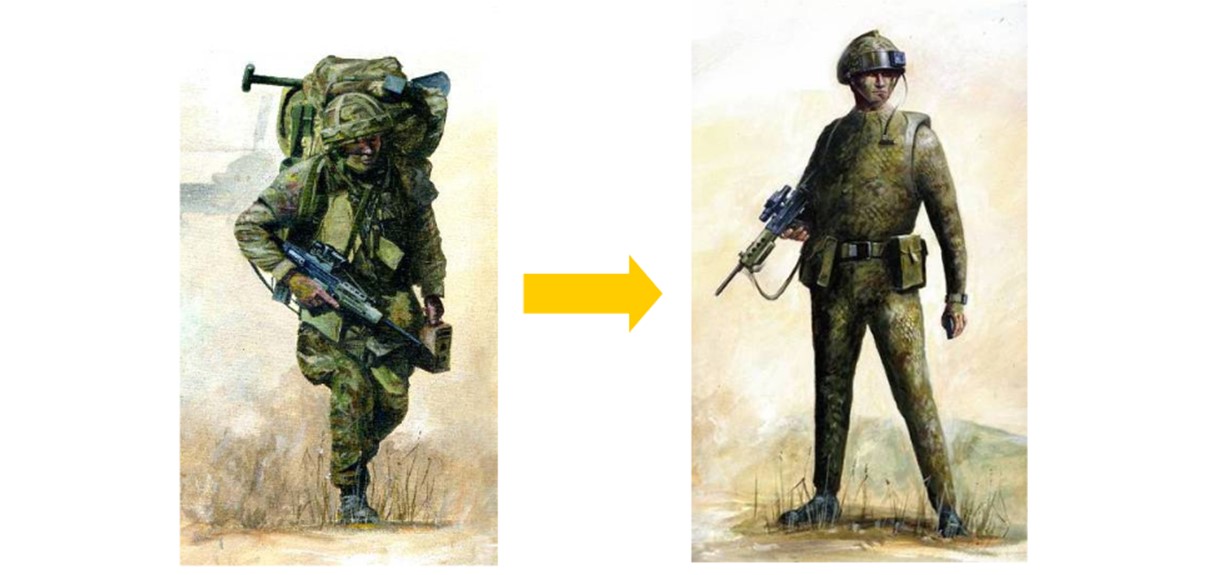

After exposure to combat operations, weights tended to fall as soldiers discarded all that was not essential, the image below shows Polish soldiers at Cassino taking ‘fight light’ to the extremes!

Since then, there has been a regular round of studies, before and after conflict, from any number of nations that all conclude the same; infantry loads are too great. The distinction between ‘approved load’ and ‘actual carried load’ is also important to note; a lack of confidence in resupply reliability leads to a ‘just in case’ mentality and section and platoon equipment is distributed to individuals.

Iraq, and particularly Afghanistan, again pushed the carried weights up, recommended marching order weights were hugely exceeded in fighting order. Injuries and reductions in combat mobility were the results. The average carried weight for Operation HERRICK was a whopping 56kg (123 Pounds)

In 2011, an article in the British Army Review, and reported in the Daily Telegraph highlighted the problem.

Attacking the British strategy in Helmand, the officer claims that soldiers are now so laden with equipment they are unable to launch effective attacks against insurgents. The controversial account of the situation in Afghanistan appears in the latest issue British Army Review, a restricted military publication designed to provoke debate within the Army. Writing anonymously, the author reveals that the Taliban have dubbed British soldiers “donkeys” who move in a tactical “waddle” because they now carry an average weight of 110lbs worth of equipment into battle. The consequences of the strategy, he says, is that “our infantry find it almost impossible to close with the enemy because the bad guys are twice as mobile”. The officer claims that by the end of a routine four-hour patrol, soldiers struggle to make basic tactical judgements because they are physically and mentally exhausted.

The original article reproduced here, ends with a very interesting quote;

If we don’t work out now how we are going to lose that weight we will do the old trick of starting the next war by repeating the mistakes of this one.

The next war may well be against an enemy more able to punish our inability to reduce carried weights.

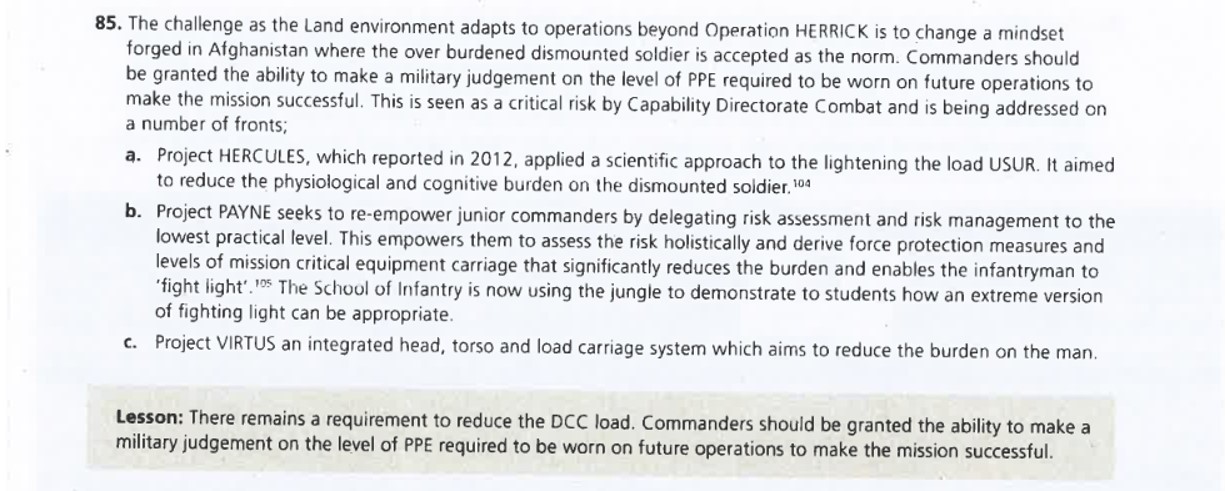

The Operation Herrick Campaign Study devoted a whole chapter to protection and ‘weight on the man’

This clearly recognises the problem of increasing weight driven by a reduction in risk tolerance and describes three key projects that are in progress to address the issue; VIRTUS, PAYNE and HERCULES, more on these later.

[the_ad id=”53403″]

The Consequences of Too Much Weight

As noted in every single one of the studies going back to the Crimean War, soldiers perform the basic tasks of soldiering more poorly the more they are overburdened, it cannot be said any clearer than that.

The carriage of excess weight has three principal effect areas.

Injury

Load carriage will inevitably result in musculoskeletal and soft tissue injuries. Some of these injuries are due to accumulations of smaller injuries over time, common in those that repeatedly carry large loads. Foot blisters and subsequent infection, stress fractures, knee injuries, digitalgia and meralgia in the lower limbs, brachial plexus palsy (backpack palsy) and injuries to the pelvis and lower back all increase in line with increasing weight stresses and are often compounded greatly as weights increase. Mounted personnel, when dismounting from vehicles, can be subject to excessive stress and vibration-induced injury during long periods inside a vehicle can also be compounded by excess weights. Gender also impacts the types and incidence of injury when subject to excessive weights and many studies have demonstrated how this will be a significant issue as more roles are opened to women.

As the British Army has reduced in size, the proportion of soldiers medically downgraded due to excess weight carriage will be disproportionate to total strength, it is a problem we can ill afford, either on operations or across a longer span of time.

The reduction in short and long-term injury rates alone presents a compelling case for carried weight reduction.

Physical Agility

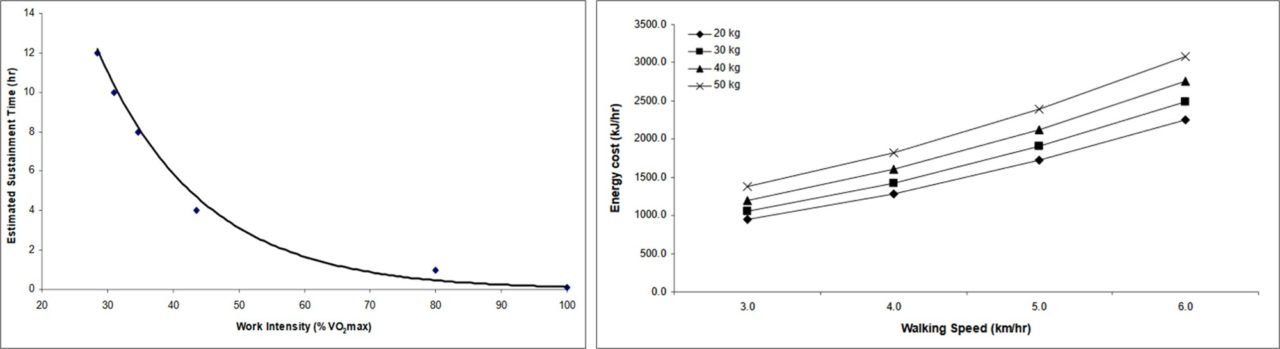

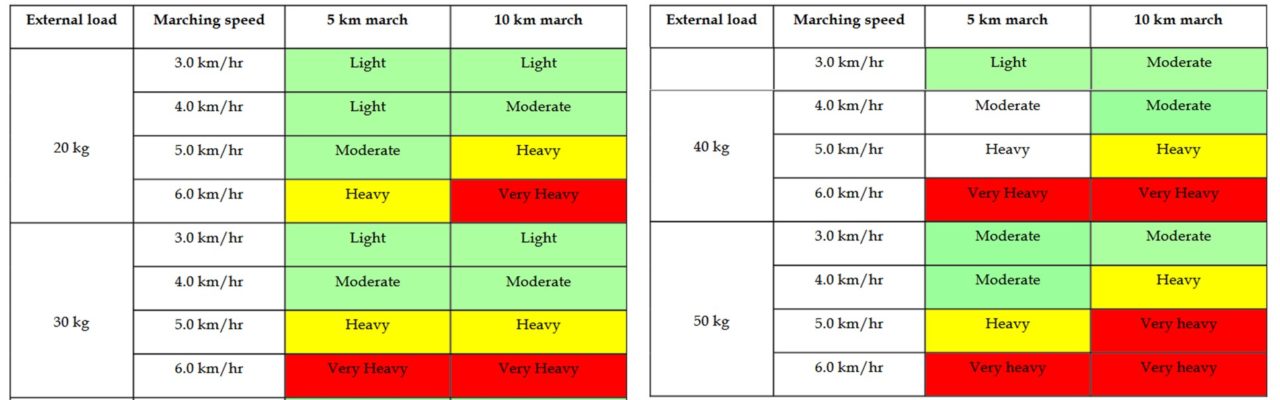

Energy costs due to loads are commonly reported in terms of kilojoule (kJ) per unit of time or oxygen uptake. A number of studies have been completed that allows a reasonably accurate prediction of the energy cost of multiple activities in different environments. Comparing this with an individual’s maximum aerobic capacity allows some measure of sustainment capacity. Task intensity measured against individual capacity provides a good way of defining how weight can impact performance e.g. the more intense the activity the less time it can be sustained, and vice versa.

The graph on the right shows walking speed energy use at different external loads, from 20kg to 50kg. If the reference is a 20Kg external load, 3km/hr on a flat firm surface, increasing the weight to 30kg results in an energy requirement increase of 12% but if the weight is increased to 50kg, it goes up by 50%. This can be translated into rules of thumb for weights and speeds, characterised by the table below.

Duration task, terrain, climate, altitude and individual fitness will all have an influence but as one might expect, more weight makes every task harder and/or slower. Recent studies (Silk 2010) demonstrated an average decrease in soldier mobility performance of 1,5% for every 1kg carried. Another study (Basaan 2005) looked at the time to complete an obstacle course and found that for every 1kg increase in external load (between 15 and 42kg) the time to complete increased by just under 8 seconds.

Terrain accessibility is also a significant factor for overburdened personnel, the images above show soldiers having trouble crossing even small gaps unaided, speed across them is also clearly limited, presenting easy targets to enemy forces. Muscle fatigue will markedly decrease weapon accuracy, requiring a far greater weight of fire (and yet more weight to be carried).

Mental Agility

In addition to physical factors, exhaustion from excess weight can reduce cognition and the ability to make sound decisions or operate complex equipment. When carrying heavy equipment it has been shown that overlooking visual clues to threats increases and decreases reaction times.

In summary, mental alertness will decrease with increasing weight, this again makes an overburdened soldier a less effective soldier and one that is more vulnerable to enemy action.

Strategies to Reduce Carried Weight

Whilst the absolute weight has increased over time the relative weight has remained, except for recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan where both have increased markedly. All this despite the advances in electronic miniaturisation, power density and logistics availability. It is, therefore, an enduring requirement to mitigate the effects of excess weight but given the recurring nature of the problem, it is abundantly clear that doing something about it is much more difficult than talking about it.

If we know increasing carried weight is a Bad Thing™ how can the problem be solved?

Quite simply there are four general approaches;

- Carry less stuff

- Make stuff easier to carry

- Make stuff lighter

- Get someone or something else to carry the stuff

Carry Less Stuff

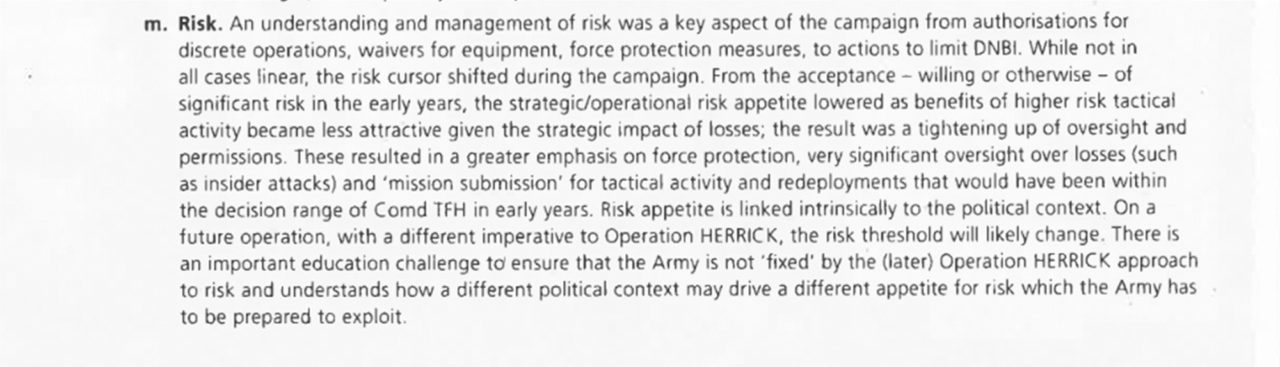

Carrying less is paradoxically the easiest and quickest option yet the hardest to achieve in practice. Risk management was accurately described in the Herrick Campaign Study.

This is probably the most significant challenge that faces the Army in terms of ‘weight carried’ because it requires an organisational shift and unwavering support from the chain of command all the way up to the ministerial level. If local commanders are not confident that a risk-based decision to reduce weight by reducing protective equipment or carrying less water or ammunition will be backed, they will simply default to the lowest risk approach, regardless of mission success or even actual survivability.

Local commanders cannot second guess post-conflict litigation against the Human Rights Act or Coroners Courts judgements whilst making tactical or operational decisions. If we are to practice mission command, this means empowering local commanders to adjust weights as they see fit and eliminating the long-handled post-conflict legal screwdriver. Project PAYNE is underpinned by risk and tactical trade-offs and it is hoped that is fully supported by the chain of command all the way to ministerial level.

Make Stuff Easier to Carry

Weight in absolute terms needs to be reduced but there are other means available to make carrying it easier, more efficient and less injurious.

Training and Conditioning

In recent years there have been many advances in understanding biomechanics and how training and physical conditioning programmes can be tailored to both individual and collective requirements. Implementing individual training programmes based on soldiers specialisms and starting points may be expensive but if it yields lower injury rates and improved ability to cope with the excess weight it could yield significant benefits that outweigh costs. Modern load carriage equipment like Virtus are increasingly person-specific and this would simply be extended to include training.

As dismounted combat roles become open to women, this individual approach to training will be needed even more so.

Load Carriage Equipment and Carrying Smart

Weight is only one part of the equation, the carriage and distribution of that weight can either reduce or increase the impact. Tailoring equipment carried depending on the phase of an operation also allows weights to be mitigated, marching and fighting order (CEMO and CEFO of old) are well-established concepts and load carriage equipment reflects this. Project PAYNE sprung from Afghanistan observations and the dramatic increase in carried weights. Although some think the name is a humorous play on words, it comes from Fusilier Tom Payne, 11 Platoon, B Company, 6 Royal Welch Fusiliers, a soldier from WWII used to illustrate some of the points about carried equipment in the training materials.

It proposed a scalable and appropriate approach to both firepower and load carriage. Load carriage would include;

- Immediate Level 1 (IL1) – Vest

- Immediate Level 2 (IL2) – Belt

- Immediate Level 3 (IL3) – Daysack

- Support Level 1 (S1) – Bergen

- Support Level 2 (S2) – Holdall

Without going into too much detail, each level would hold different amounts of equipment that would be carried or dropped off at different stages in an operation. It is an intelligent approach to carrying only equipment relevant to the demand at any given point in time. Read more here

Although it predated Virtus, it clearly required a new system of load carriage equipment. QinetiQ provide a good overview of Virtus;

Project Virtus is aimed at delivering a new body armour system for infantry which will increase agility and make it easier to carry heavy equipment. Established by UK Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S), Virtus replaces the Personal Equipment and Common Operational Clothing (PECOC) project. As the foundation of infantry Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), Virtus will deliver an integrated head, torso and load carriage system with a built-in quick release capability. It will be used by dismounted close-combat soldiers including soldiers, marines and airmen involved on land, littoral manoeuvre and ground support to air operations.

One of the key features of Virtus is scalability.

The Scalable Tactical Vest (STV) can be used for load carriage without any armour; as a fragmentation vest with soft armour padding consisting of a composite granular material but no hard plates; as a plate carrier with no soft armour; or as a full body armour system with soft and hard armour. It is compatible with both Osprey and Enhanced Combat Body Armour. Any combination of front, rear or side plates can be employed.

The rest of the system is equally integrated and scalable.

A new, lighter helmet will provide increased blunt impact protection, face and mandible guards for certain roles and a shape that is designed to work with the armour and daysack so weapons can be comfortably used even in a prone position. One of the most radical innovations is an integral ‘spine’ – the ‘dynamic weight distribution’ system. The device is linked to the user’s waist belt and helps spread the load of the body armour, a Bergen or daysack across the back, shoulders and hips. A lightweight webbing system is designed to be worn under and integrated with the body armour. Both the daysack and Bergen are fully integrated with the rest of the torso sub-system. This ensures that they are carried close to the body preventing excessive movement of the load but without pushing the rear ballistic plate into the body. Both can be used in conjunction with the dynamic weight distribution system. Pouches are made from one piece of fabric and fold flat when empty, minimising profile and the possibility of snagging. The dynamic weight distribution system contains a hard spine that takes the load and is linked to a hip belt. This allows the soldier to transfer the weight of his load from the shoulders to the hips or the other way via an adjuster positioned in the small of the back. The Virtus helmet has a fixed shroud for the mounting of night vision goggles and a counterweight for neck comfort. Its fit can be easily adjusted in the same way as modern cycling and climbing helmets. The sculpted rear prevents interference with body armour or daysack when adopting a prone fire position. It provides more protection to the side of the head and is 350g lighter than the Mk7 it succeeds. The helmet can be fitted with both mandible guard and visor, or either, which provide face protection for crews in open vehicles such as Jackal or WMIK.

Of course, no new load carriage system will be without its problems and Virtus was no different but it is likely to evolve and improve and represents what I think is a genuine innovation. Above all, it supports the concept of scalability.

Read more here

VIRTUS and PAYNE aren’t enough on their own to get close to the objective, but they are important components of the journey.

This news piece about Afghanistan from 2006 illustrates the problem where trolleys might have been useful, members of the US 10th Mountain Division hauling water bottles with stretchers and a ‘bucket brigade’.

For the want of a wheel!

A trolley or handcart does not need to be the result of a huge research programme, the leisure and industrial markets have all the required components. There are also a number of manufacturers that manufacture similar products, the Handimoova and Wheelz for example (more Wheelz examples here). Zarges make large wheels and a handles for some of their larger boxes and for moving heavy loads over short distances, breaching stores or power tools in an urban context, for example, powered wheelbarrows would be useful, especially if they had a common battery with those power tools.

For supporting carriage over longer distances, there are a number of simple wheeled pack supports available, Carrix, Dixon Rollerpack and Monowalker for example. Simply put, wheels allow heavy loads to be carried over longer distances with less effort than carrying them in a Bergen (rucksack). Disadvantages include parasitic weight and difficulty in using them in difficult or mixed terrain so they would only really be useful on flat and firm terrain, anything else would make them useless, but for speed over ground and IF the terrain supported it, they have a lot to offer.

Now I will be the first to admit, they are somewhat lacking in credibility but if a glorified grocers trolly was good enough for the men that did the whole Arnhem thing, it really should be good enough for today. No doubt these are less practical but keeping an open mind and experimenting with means of reducing energy on long road marches, despite the equipment actually adding weight and having to be transported to theatre, cannot be a bad thing, they might work, they might not.

Make Stuff Lighter

The excellent UK Land Power blog collated a list of current infantry loads recently, click here to read it, broken down by category and in four groups;

- On the Soldier, 18.96kg

- Assault Order, additional 12.55kg

- Patrol Order, additional 16.26kg

- Marching Order, additional 16.17kg

On the Soldier and Assault Order together weigh 31.5kg, marching order tops out at just under 64kg. This is with the latest Virtus load carriage equipment ECBA plates and represents a ‘standard rifleman’. As noted in the linked article, absent from the list are radios beyond the Personal Role Radio, support weapons, ECM, weapons other than SA80, breaching equipment, Vallon detector, the Underslung Grenade Launcher (including FCS), 7.62mm link and various items of ISTAR equipment. It is therefore on the light side of what will actually be carried. So no matter what the weight reductions of some parts of Virtus, it is still some way off the accepted maximum of 40kg and target of 25kg for the ‘Energy Efficient Soldier’

Equipment carried can be broadly described as personal and collective.

Protection and Personal Equipment

For personal carried weight, the approach taken by ultra-lightweight hikers and backpackers can yield useful savings, so whilst cutting a toothbrush handle in half or spending a tenner on a 6g titanium spork might garner derision, it is worth bearing in mind that in the studies described above, a single kilogram saving provides a demonstrable mobility and cognition improvement. Every bit really does count. That said, there is only so far one can go with lightweight ‘life support’ type equipment, the real big hitters are protection, weapons and electronic equipment.

Lightweight plate inserts are also a promising avenue for weight reduction and materials technology improves.

Power and batteries are a significant proportion of soldiers carried weight. Communications, ECM and ISTAR equipment has a voracious appetite for power and this is compounded by different types of battery. Every watt of energy left over at the end of a mission is weight needlessly carried and if this energy is distributed across multiple battery types, the problem is compounded by leftover energy distributed in those multiple types. The small battery problem is a particular challenge; sights, illumination and other small devices in service variously use 1/3 AA, AA, CR123, CR2032 and CR17345 types. Potentially, on a single weapon, there are three of four different battery types.

This is before we get to the larger batteries, where thankfully, progress has been made, they are still heavy though simply because of the energy demand. Lincad has the excellent LIPS range which has evolved continually over several years and increased energy density so that fewer now need to be carried. Fuel cells may well provide useable weight reductions as they develop but seem someway far from a readiness for a combat environment.

[the_ad id=”53403″]

Another promising means of stored energy and weight reduction is to take a systems architecture approach and here, the MoD may well be significantly ahead of the curve. I have written several times about the Land Open Systems Architecture (LOSA) and specifically Generic Vehicle Architecture (GVA) (here for more detail).

As can be seen from the diagram above, Generic Vehicle Architecture is one of three, Generic Soldier Architecture (GSA) is described as;

The GSA is a platform-specific architecture, the physical implementation of which is the Dismounted Soldier System (DSS). GSA defines the infrastructure to be implemented by DSS and the interfaces between it and the soldier’s role equipment. Architectural components and requirements that enable off-soldier communications and connectivity, including data sharing, between platforms, will be captured within the Land Open System Architecture (LOSA) Common Open Interface (Land) (COI(L)) Defence Standard.

Benefits are said to be;

- Enable ‘plug and play’ of legacy and future systems for soldiers.

- Provide interfaces that comply with publically available open standards.

- Promote third-party competition by providing modular components.

- Promote innovation and diversity.

- Allow incremental improvement of systems.

- Reduce the whole life cost of ownership across all Defence Lines of Development (DLOD)

- Facilitate technology insertion into existing systems

- Reduce the burden on the individual soldier from a weight, cognitive and thermal perspective.

- Make the best use of COTS.

- Improve operational effectiveness,

Both Ultra and BAE have recently demonstrated GSA compliant products with the BAE Broadsword Spine system looking particularly well developed. One of the key features of Broadsword is a centralised battery contained within the harness that is used to power all soldier worn electronics. One of the particularly innovative features is the inductive ‘wireless’ charging pad on the back. A soldier would simply charge the central battery by sitting in a vehicle seat equipped with a charging coupler. This is not dissimilar to the Bosch tools wireless charging system.

A new revision of DEF STAN 23-012 (Generic Soldier Architecture) was published in October 2020 and it seems the development of compliant solutions is accelerating, with a possible move to the USB 3.1 standard and various conventional and specialised military connectors for higher data rates and more power capacity. Integrated soldier electronic systems have a scope much broader than weight reduction but certainly, weight reduction via the elimination of duplication is a key part of the approach.

Small Arms

Small arms calibres and types is a tremendously complex (and somewhat emotive) subject but what Project PAYNE did was recognise that firepower must be tailored to operation type and environment. The concept of the one true ‘section firepower mix’ is false. In a complex counter-insurgency type mission, excess protection and greater amounts of suppression firepower may well be the optimum choice, for a conventional assault operation, different thinking may be required. Many have noted that whilst the 5.56mm LMG might be excellent for close urban terrain, at ranges in excess of 200m it is an excellent way of turning money into noise but very little else. Therefore, weight reductions may be obtained by simply changing the section firepower mix.

The SA80 is a heavy weapon, with an Underslung Grenade Launcher, Fire Control System and sight, it is even heavier. The UGL fire control system, especially, adds significant weight to the front of the weapon and is a good example where weight reduction obtained in one area (swapping the steel magazines for polymer ones for example) is then negated by added weight elsewhere. The A3 variant will reduce weight even further but it is still a heavy weapon and so as the British Army starts to look beyond the A3, weight should be one of the main selection criteria.

Polymer case technology also looks very promising as a means of weight reduction, Textron is working on conventional and telescoped rounds in a variety of calibres (5.56mm, 6.5mm and 7.62mm). In one example cited, using polymer cased ammunition resulted in a 12kg weight saving in a typical setting for an M240 team and a reduction of 39% over 5.56mm (200 rounds belted). Another example is the Textron 6.5mm CT Carbine that weighs 3.8kg; compare that to the SA80A2. PCP Ammunition also claims to have a working solution for polymer cased ammunition.

Putting aside the arguments about intermediate calibres, polymer cased (telescoped or conventional) offer the potential for significant weight savings and must be considered to be an important future technology for small arms.

Improving combat marksmanship through more frequent and realistic training is also a not unreasonable weight reduction strategy to pursue.

Collective Equipment

It is often the collective equipment that both piles on the weight and has less of an organisational focus on weight reduction; ECM, batteries, spare link, GPMG SF tripods, mortars and mortar bombs, Javelin/NLAW, section radios, breaching equipment, stretchers, ladders and a plethora of other equipment is added to the infantry soldiers burden.

Lighter GPMG’s are also available, likewise 81mm mortar baseplates (14% lighter). Both these weapons are arguably more valuable than any other and yet we have not pursued weight reductions via design and new materials with any great zeal. The US has recently developed a lightweight Javelin CLU that is 70% smaller, 40% lighter and with a 50% increase in battery life. It also has a range of other improvements, GPS and network connectivity for example.

Both these are available off the shelf and would require only minimal changes to support and training arrangements.

The much-missed 51mm mortar had a range in excess of 600m and weighed just over 6kg. When it was replaced with the 40mm UGL and flares, the ammunition ceased being manufactured, leaving a rather significant range gap. When the requirement for a lightweight infantry mortar was predictably rediscovered in Afghanistan, the MoD purchased the Hirtenberger M6-895 that weighed over 10kg. The individual bombs were also much heavier, and the UGL stayed in service anyway. This is a classic example where weight has increased for marginal capability improvements. There are alternatives to the Hirtenberger and it might be worth exploring these. The Le lance Grenade Individuel Mle F1 (or Fly-K) is in service with the French Army and uses a closed combustion chamber to propel a 51mm bomb (illumination, smoke and HE) to a maximum range of 675m. It weighs 4.8kg and has a range of interesting accessories for ambush and area defence use. Rheinmetall has also developed a digital aiming system that it claims increases the effective range to 900m. The Antos 60mm system, recently been purchased by Poland would be another alternative, at only 5kg.

A more radical approach to attacking the weight of communications equipment is to recognise that in a COIN environment, a deployable mobile telephone infrastructure or trunked mobile radio system like TETRA/TERTRAPOL might be perfectly acceptable in comparison with conventional systems. By deploying such infrastructure, especially TETRA/TETRAPOL that does not need a base station every 500m, the weight of receiving equipment can be reduced to that close of contemporary mobile telephones. TETRAPOL might not deliver high bandwidth imagery and live video but it is perfectly capable of managing end to end encrypted voice and text messaging. A single TETRAPOL base station can comfortably cover 25km and handle 2,500 users. The latest Airbus TPH900 handset has a 13-hour battery life, text and status messaging, vibrating mode, covert controls and location reporting and GPS, yet comes in at less than 1kg. By accepting the trade-offs of deploying a vehicle or container-based TETRAPOL base station, considerable weight can be shifted off the soldier. NATO used this approach in Kosovo and the Bundeswehr deployed similar systems to Afghanistan.

We might think TETRA/TETRAPOL is an old-fashioned system but it is reliable, functional and critically, allows the weight to be moved to a base station, as long as we accept the limitations of a base station with 25km range. The RAF’s Zephyr High Altitude Pseudo-Satellite (HAPS) has also been reported to include an option for a TETRA/TETRAPOL base station which would allow continuous coverage over a much greater area. Clearly, this would not be applicable to conventional operations against a well resourced and equipped enemy, but it should give food for thought as Project MORPHEUS progresses, trading off high bandwidth for simple secure voice and messaging and accepting limitations of a base station approach can yield significant weight savings for both the equipment and batteries used to power them.

A good example of simple innovation and well-executed design, rather than expensive development programmes, can yield significant weights savings is the XtractSR casualty evacuation system from TSG Associates. Another example is the collapsible tube technology from Rolatube.

Get Someone or Something Else to Carry Stuff

The British Army has a preponderance of light role infantry and there is certainly an argument for greater mechanisation but assuming light role infantry endures, using lightweight vehicles to carry collective and personnel stores is a tried and tested solution. One of the issues with using vehicles to carry light role infantry stores and equipment is they would absorb finite personnel and increase the support burden, thus reducing the very high ‘bayonet count’ in light role infantry battalions. They also have to get to the battlefield and be sustained themselves whilst there. Many terrains will be completely unsuited to a vehicle, even a quad, so the concept of providing vehicular assistance can be easily stretched to breaking. But if we accept these limitations, quad and ATV type infantry support vehicles would seem to offer a great solution that can be obtained quickly and cheaply. Quad bikes and trailers are therefore tried and tested, and there is still growth potential and additional capability, especially with trailers. These are detailed in a separate long read here. A more recent long read on Helicopter Portable Vehicles details the full range of ultra-lightweight crewed and uncrewed vehicles, all of which would provide support to dismounted infantry.

All of these would be excellent means of helping dismounted forces to carry less weight, approximately 750kg across a typical platoon.

Perhaps more esoteric systems like powered exoskeletons and delivery drones might be the answer but again, there are downsides to technology maturity and tactical applicability.

Drone deliveries might look great but a competent enemy would simply use them as a very handy means of determining the next mortar aiming point (something I think we forget in our rush for technology). There is still self-evidently a lot of potential with some interesting solutions in advanced testing. The most prominent in UK terms is the Malloy Aeronautics (makers of the Hoverbike) T-80 and T-150 which can lift 30kg and 68kg respectively. These are impressive machines with excellent performance, currently being tested by the Royal Navy and Royal Marines in various roles.

And as we all know, muscles don’t have to be human.

Summary

The issue of overburdened infantry is as old as infantry, and there is the problem.

Whilst there is an ongoing debate about the validity of light role infantry in the contemporary operating environment, the fact remains that historical evidence and a reasonable look at the future informs a viewpoint that there is an enduring role for light infantry. We cannot assume support helicopter availability or that patrolling at short distances from operating bases will be the norm, and neither can we assume that vehicles will always be operable in the terrain where our enemy is. So if we are at all interested in winning the close battle we must take note of the issue of overburdened infantry soldiers because whatever the next conflict might be, there is a very real danger we will be punished badly for not addressing it. Against a well organised and well-equipped enemy, dismounted infantry may well be subject to significant amounts of observation and detection with a likelihood of accurate indirect fire soon after. As the BAR article described above noted, excess weight leading to decreased mobility is a tactical matter above all else.

But balancing protection and mobility is far easier said than done.

The amount of research that goes into protection is enormous, just as one example, this one looks at neck protection on Osprey and the requirements for Virtus, click here to read. The amount of protection has gone up and up and whilst some individual systems might be lighter than earlier generations, they still represent a significant percentage of the carried weight. There is continuous and ongoing work to reduce weight, some technologies may not mature for decades so the risk question has to be addressed.

But fundamentally, the key issue is not one of weight, it is the inability to take a risk-based decision without defaulting to turning infantry into tanks.

Arming unit commanders with an ability to make a risk-based decision is fundamental, especially if they evaluate that going ultralight will be essential to achieve objectives. Risk training and providing confidence that they will not be crucified by a lawyer after the battle will mitigate instances where risk aversion results in no risk-taking. Soldiers are professionals and it is about time we let them get on with their jobs, they understand the risks and the corporate culture of the MoD, no matter what the political cost, needs to reflect this. The reality is that in the majority of cases full protection would be the order of the day but commanders must have the flexibility to act as they see fit.

We also need to be wary of excessive technology; energy harvesting from smart fabrics and powered exoskeletons may well be part of a future answer but at what cost and when?

Chasing unicorns instead of getting on with taking practical steps now, no, let’s not do that, the issue is now and hoping for future technology to solve our leadership issues is foolish. It is probably the case that the infantry receives the least amount of investment per person than any other arm. This needs to stop, there are easy options for modest costs available now, much better in terms of return on investment than spending money on drone research for the last mile deliveries, however tempting that is. If some of the approaches of fight light are to work, those that supplement infantry with quads and ATV’s for example, there must be confidence in the logistics system that allows them to fight light but not freeze at night. This means, again, modest investments.

Our strategy should therefore be;

- Empower leaders to make informed risk-based decisions about protection levels

- Training

- Exploit immediate and incremental opportunities by purchasing reduced weight components that are readily available

- Continue with existing research programmes and systems architectures like GSA, keep a watching brief on systems like polymer cased ammunition for medium-term weight reductions

- Accept that until the higher technology systems mature, invest in carriage support for individual and platoon stores

None of this is easy, but as shown above, it is hardly a trivial matter either, the consequences are very serious. Ultimately, much of the problem is about organisational focus, discipline and leadership, something the British Army prides itself on.

Table of Contents

[adinserter block=”1″]

[adinserter block=”1″]

Change Status

| Change Date | Change Record |

| 01/03/2017 | initial issue |

Further Reading

https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

A report from Afghanistan in 2003 ,15 years ago! also illustrates the gross overburden put on modern combat troops which has led to many vets having long term health issues putting extra burden and therefore long term COST on the government.

https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://thedonovan.com/archives/modernwarriorload/ModernWarriorsCombatLoadReport.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjp5YSE5OzYAhWM6qQKHVgUAdcQFjAAegQICBAB&usg=AOvVaw05HCfI4XTZ00Wh5t9R7Q-1

“If we truly want to reduce combat loads, logically, there are only two remaining options;

Make stuff lighter

Provide assistance”

I disagree. It’s an utter necessity that the land forces bureaucracy learns self-discipline. The lack of it is the root cause of the never-ending drama about the infantrymans’s load. The problem is known from antiquity and middle ages, when it was mostly solved with servants and mules, and studies on the subject already appeared in the 18th century when despite the simple armament with musket and bayonet about 30 kg were carried by a common infantryman.

Lighter gear and airs in transportation only lead to more equipment if there’s no self-discipline to keep the load right for a desirable level of agility.

Lighter stuff has to be the 2nd step, it does nothing towards reducing the infantryman’s load by itself.

That being written, ultralight backpacking-optimised gear (including frequent replacement of gear to make up for lesser durability of some items) shouldn’t be too expensive for infantry. Heavy weapons and munitions should be issued / taken from motor vehicles only when a need for them is likely.

The Donkeys article took us 6 months to write and another year to get published due to its alleged controversial content (not following happy-clappy media ops fiction) yet management still surprised by the findings. The “unnamed officer” author was really a gaggle of soldiers and an analyst.

Good Article with excellent insight.

Back in 2012 I wrote a post Conference Summary for Infantry Weapons 2012 (London).

The Summary is available at: https://independent.academia.edu/PhilHarrison3

My conclusion, at that time, was that the infantry needed to adopt the equipment mind set of the Special Forces. The SF concept is to tailor the equipment to the geography, environment and the task. The stock answer from the; ‘top brass,’ was always the cost and the inability of the average infantry to cope with a wider range of equipment options. The equipment flexibility approach was called; ‘The Golf Bag Concept.’

The logistics can be supported if there is sufficient will and determination at the top.

As the number of infantry units has steadily decreased, there has been a great opportunity to improve the resource options and to enable individual units to tailor their equipment to the theater, environment and task.

I believe the cost of additional equipment and training, to implement the Golf Bag Concept, would ultimately be less than the psychological and physical costs of failure in the field.

Sven, that bit you quoted is after the others that shoudl come first, discipline, training etc. Its not very well worded though, will update

Thanks Dermot, an interesting point!

Thanks Dhooghe, will have a read

To follow up on Sven’s point, this is not an issue solely for the Infantry. The lack of discipline, or perhaps more accurately the compulsion for excessive caution, results in overburdened vehicles as well as overburdened soldiers. On exercise at Imber on the Salisbury Plain ranges in the 90s I found a Sultan command vehicle on duty. When asked its weight the vehicle commander said they had drawn a line when it reached 12t because it was running on the bump-stops and had no mobility left. According to Alvis the max weight was 9t. Everything they had added to the vehicle had military utility, but probably only be necessary once a decade. It was all carried ‘just in case’.

Sadly its really difficult to persuade the military that some of the cautionary belt-and-braces kitting out needs to be abandoned if properly agile fighting forces are needed. This caution is embedded in the procurement specs as a result of the process used to generate the requirement, after all. This because the first stage of requirement definition is to ask every User group what they need the equipment to do. So every User will naturally list all the capabilities and all the kit they might need to carry along on all their different tasks and roles just so when its necessary the new equipment is capable of performing the task. This then translates to the System Requirement which is not written by the User in which all the User needs are required to be accommodated. Not subsets depending on the tasking, rarely FFBNW, but ‘shall be fitted with’ and ‘shall be capable of’.

So in vehicle terms recce goes from the WW1 bicycle to the WW2 Jeep to the 4t Ferret to the 9t Scorpion to the 40t Ajax as more and more ‘just-in-case’ness is added.

I suspect the same applies to the foot soldier, that much of their load is just in case really bad stuff is going on and they are isolated from their comrades and have to rely on just what they carry to survive? Realistically is there duplication of carried kit within the squad? Is there stuff carried that would never be useful in a specific theatre? Is the set of equipment/PPE carried merely to avoid Command, MOD and Government from being accused of Duty of Care laxity? Or is it just that every soldier in every action needs every bit of kit that is attached to them in order to be militarily effective?

Followed the Virtus testing reports (what little trickled to the public domain) with great interest and one of the toughest nuts to crack was (alledegle?) getting back onto the feet; how was the stiffness, introduced by the “spine” and obviously giving great benefits, solved in the end?

Great article… on an important topic.

TD,

As a total non-expert in the land warfare element I think this is fascinating. However it brings up an interesting point regarding risk.

We have trained and generated a whole generation (perhaps more) of both soldiers and politicians to accept that protected mobility is possible, and that the body armour and ‘golden hour’ medevac coverage means that soldiers will survive almost anything. On that basis, I can’t see how we can realistically reduce loads if it increases risk. It smacks of the same argument which erupted over Snatch and led to the introduction of Mastiff, Jackal and other vehicles that now also suffer from a loss of mobility. How you counter that, I have no idea.

Fascinating!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKFkrMTlPzs

On 7 July, the Army communicated on this subject, recalling that it has defined a new clothing policy, which distinguishes combat equipment, sportswear and regimental uniforms, as part of its “Combattant 2020” project.

“Equipment plays a central role in a soldier’s operational capability. Be more mobile, better protected, evolve in comfortable equipment, be able to communicate at any time with other units deployed in a theater of operation, etc. are so many issues and criteria that require “their regular evolution.

This evolution of the individual equipment of the fighters thus passes by new combat shoes designed especially for the hot environments (more to have soles which take off under the effect of the heat, as had been reported at the time of the Serval operation in Mali), “reinforced” combat gloves while being compatible with tactical screens, and improved ballistic glasses. Even the underwear will be concerned, especially to fight against the cold. In addition, a new composite helmet is announced.

It is also planned to equip, in 2018, the fighters of the new mesh F3 “adapted to the new threats” and obviously compatible with the version 1.3 of the FELIN system (infantryman with equipment and links integrated), supposed to be lighter (-10 kg) and modular. The latter will be based on a new individual ballistic protection vest which, called “Electronic Ballistic Modular Structure” (SMBE), has been ordered to 31,600 copies from the Norwegian company NFM Group.

Specifically, this vest provides class 4 ballistic protection against piercing ammunition. It features high-velocity ammunition-shielded plates, a “built-in anti-traumatic mattress in the soft ballistic pack”, and protection against knives. Finally, with its complete ergonomics to “optimize mobility”, it has the First Spear Tubes quick coupler system. Modular (up to 8 possible configurations), it integrates the electronic equipment of the FELIN system.

Having gone through SERE training I can tell that you don’t need much equipment to survive . A layer and some warm clothes is all you need. Also having done some backpacking with rifle the amount of gear needed to survive long periods of time isn’t that much. Once you realise you can’t carry all the water and food needed for say two weeks it gets much easier to travel and plan the mission. Mission critical and survival critical equipment has to carried to matter their weight but after that it’s all personal comfort. Personal comfort or 15 pounds less of gear to haul?

I once read from Infantry a magazine a story about dismounted recon patrol. An FO had joined one recon patrol and the patrol leader had checked all of his soldiers equipment to make they had all what they needed and only what they needed. He hadn’t checked the FOs backpack because he was a junior officer and had taught that he knows what to pack. They started moving toward their area of operations through harsh terrain and soon the FO was exhausted and became a burden for the recon patrol. After a closer inspection they found out that the FO had chips, energy drinks and other unnessecary and unsuitable items in his pack. Dismounted recon troops know the value of every pound they carry and they have to keep the weight down. Helmets and body armor are a big no no for them.

Has anyone looked the number of hits on body armour in say Helmand and how many lives have been saved by its use? perhaps lighter soldiers would be more effective in pursuing the enemy and thus reduce their vulnerability.

The problem is also all the new tech that is coming out with the new ‘fight for information’ doctrine.

Even without any body armour, my pack is already 50-70kg. And I weigh 82…

It’s utterly insane but all of it is ‘mission critical’ equipment, it’s gotten so bad we don’t even bring food out any more. Binge eat before mission, binge eat after, snack on hardtack in the meantime.

I’ll give a list of what is in the pack for a 4 man team

1-Panasonic Toughbook

2- 3 CPUs with assorted sensors

3- Thermo-imager

4- Binoculars 40×100 and 80×120

5- Signals set

6- Modem

7- Night Vision Goggles

8- Night Vision Binoculars

9- Foldable stretcher

10- Medical kit

11- TAG panel markers

12- Groundsheets

13- Machette

14- Dipole antennas

15- Log Periodic Antenna (for rebroadcast team only)

16- Skyblade UAV (for UAV team only)

17- Batteries for all the above

18- 2x 1.5 litter bottles of water per person

19- Entrenching tool

20- Digital camera with telescopic lens/waterproof lens

Let us not forget the weapon, ammo and smoke/frag grenades too…. the Commandos also carry a foldable spade

New war doctrine, same old legs.

We need to mechanize.

I see Sig have just launched their model 365 9mm pistol. The size of a Walther PPK, but loaded with 10x 9×19 ammo. Would be easier to lug than a Glock 17 or 19. Same size as a Glock 26, but thinner. The 365 is aimed at the US self defence market, but would be handy for the sneaky units & any unit wanting to save weight & bulk.

In the days before suitcases had wheels, I had to lug my huge suitcase(under the African Sun) the several miles between the Zambian & Zimbabwean border post next to the Vic falls. Taught me a lesson about packing light. Could someone invent an easy on/off backpack with wheels? When you are on a road or a hard, smooth path, you pull it on wheels . You put it on your back, when the ground is muddy or too uneven.

JH, at certain levels of overweight, you don’t ever want to put your pack down if you can help it, when you’re tired, the effort needed to straight lift the pack to your shoulders can seem insurmountable. It’s mentally better to just keep it on. At this level, you ‘rest’ by leaning on a tree or any convenient surface. If you made the ‘mistake’ of putting your pack down, you ‘get it back up’ by sitting down, slipping the straps on, then pulling yourself up via a tree or fence or a helpful buddy. Or roll over and crawl to the nearest support.

If your fieldpack is heavy, don’t ever put it down unless you’re setting up camp. The effort needed to get it back up is not something you want to do without some prior rest. Yes it is that bad. Remember, airline luggage is 35kg more or less. We’re talking 50-70kg here.

@Obs, yes ” you ‘rest’ by leaning on a tree or any convenient surface”

As a lot of my hiking is in National Parks, they don’t even have tree stumps, from felling the trees. So always on the lookout for suitable storm damage

I’ve never had to carry over ~40kg backpack and even then I had gear for a week and VHF radio with all be whistles and bangs. Ammo would have added about 2-3kg. And it was in winter.

Teh, I put up a list of what my team carries 5 posts above, for a 4 man team. Cross reference with your loadout to see the difference.

If I only had to carry a signals set, I’ll laugh all the way to the objective.

So,we could take the land rovers,but that would be denying your human rights. You’ll have to walk.

Very interesting article.

If we’re inserting troops with a 50kg pack and expecting any benefit of agility we’re living in cloud cuckoo land.

Can’t 3, 4, 7, 8, and 20 on Observer’s list be merged into a single device?

At 50kg you could almost afford to ditch all batteries and get someone to carry a 3kw petrol generator. At least then you can have a decent cup of tea. Obviously someone else needs to carry the TV for the evening movie ;-)

Simon, unfortunately no. Night Vision Goggles don’t have magnification for a reason, they’re there to help you see where you are going. Blowing up the image just gives you vertigo if you walk while using it since what you see does not correspond to what your inner ear feels.

The closest you can get is using Night Vision Binos with a perforated lens cap on to cut down incoming light, but that uses batteries and the image is a false colour one, green tint. The reason for the different binoculars is the different field of view at different focal lengths, you don’t want to overmagnify and tunnel vision at ‘close’ range nor undermagnify at long range.

As for combining them into a camera, you have to integrate it in a way that it doesn’t mess up the main function of the device. Possible but tricky and a lot less handy. A digital camera fits into your palm, the rest of the equipment is at least the width of your eyes.

Irony of it all is that I even forgot to add some things in the list, so it only gets worse. We’ve complained about it all we can, it’s now up to the brass and the think tanks to see if they can do something about it.

I’d say develop some electric drive vehicles so you can use them close to the enemy then use them as ‘mules’ or ‘motherships’. Some silenced Land Rovers, even if they were something like the Snatches would help a lot to take the weight off our backs. Batteries, ammo, food, water, medical supplies and clothes can be stockpiled there instead of being carried. Just don’t use them for predictable patrols. But I bet ‘it looks like a patrol vehicle’ so it’ll be used as a patrol vehicle….

Only good thing I can see with all this weight, once you completed a 72 km exercise with it, you tend to look down on everyone else but the Commandos lol.

“…once you completed a 72 km exercise with it, you tend to look down on everyone else…”

Bloody superhuman if you ask me.

I buggered up my knee for a whole year in a single two-day stint in the Welsh hills carrying only 20kg around a place that got named “Bastard Lake” by the group :-)

Pain is good, extreme pain is extremely good. lol

Whenever my CSM said that, I wonder if he misread his appointment letter. Company Sergeant Major, not Company Sado-Maso. lol.

He was a Basic Underwater Demo School grad, class of ’91

the 2 wheel drive packable bike that can be petrol or electric and costs absolute peanuts

A team of 12 carries and mission critical with asterix:

tent

stove

2x shelter sheets

2x VHF/HF radios, batteries, antennas and message device*

Thermal camera*

2-4 NVGs

2-4 binoculars

3-6 directional charges

1-2 LAWs

x amount of smoke grenades

Everyone carries:

Clothing

preferably bottles to hold days water ~6 liters

Trangia and fuel

batteries

Food depending on caches and lenght of mission

9 mags of ammo

medic pouch (size of magazine pouch)

knife

This one from Simon reminds me that a French squad that cannot charge their personal (Felin) kit from the squad 8×8 has one man carry a fuel cell, that others can then plug into; the weight/ power density trade off must be far superior to batteries as in a way you are introducing a single point of failure

“At 50kg you could almost afford to ditch all batteries and get someone to carry a 3kw petrol generator.”

@teh, a question: 9 x12 mags, of what caliber? Whatever the total weight, across the whole team, the caliber difference and polymer vs. metal has the potential to shave 30% off it.

– also, if it is not summer, with refreshing little becks all around you, 12 x 6 ltrs (to turn snow into water, for a refill to last over a day) would consume a considerable amount of fuel? – Factor in the length of the patrol, to come to a weight estimate

It strikes me that part of the overloading problem is down to trying to use ever fewer people to do any given job. There are aspects to that which make sense. Fewer people means fewer targets for the enemy, less logistics burden, less training expense. The advances in supporting fires mean that smaller units can do more, but that’s not really new. I’ve read some claims that the British infantry in WW2 were almost there as bodyguards for the Forward Observers. These days we give a FO a rifle and tell him to do that job himself?

While small forces with overwhelming supporting are excellent at destroying opposing forces, they have difficulty holding ground, which means that logistics is more difficult, which means that these small teams need to carry more supplies in addition to all the mission kit, which itself has multiplied so a telescope is now two different binoculars, a thermal imager, a night vision telescope and a digital camera with a telescope on it.

@Civvy

7.62×39 and polymer magazines, not all ammo is in magazines since there would probably be ~6 mags for each soldier. There’s liquid water plenty in winter too. One liter of Sinol is enough for week to make three hot meals a day and more if you boil water for them all in one go and store it in thermos.

@ Mr. Fred

That is still valid today. FO does most of the killing and if MVP placks were handed out based on number of kills FOs would get those. The rifle platoon around FO is there to protect him.

mr.fred you nailed the problem right on the head, ‘do more with less’ is killing the ‘less’ especially with mission creep. In WWII, you didn’t have NV equipment or Thermals or UAVs or Ground Sensors or laptops. Add those in to the infantry load and any sane man would cry.

There is also another reason for smaller teams though, tactical superiority, the theory is that smaller teams give a lot more points of contact for groups with independent control, which can overwhelm a less flexible enemy unit. For example, 3 fireteams can be in a lot more places and can more easily bypass a defence line than a single squad, leading the enemy ‘higher command’ to have insufficient units to plug any breakthrough. In theory.

My unit is not for direct combat so we only carry 120 rounds of 5.56 per person, which, according to the ‘book’ is a 1 contact rate, infantry carry 3 so it’s probably 12 per person (360 rounds) for an AR (1 mag being 0.25 contact rate). 5.56 though, not 7.62.

7.62×39, interesting calibre. AK derivative?

The way I was thinking was that three squads would do the job of three fire teams while being better able to carry the equipment necessary to fulfil a mission. If you need 12 things, 12 guys can carry that extra load better than four guys carrying three things each.

Trouble is, that 12 guys are much easier to spot and engage than four, and more costly to deploy and support.

Observer,

if my nickname isn’t enough of a clue for you Finland uses RK62 and RK95.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=0ZfaLz3vBVM

A squad of 12 doesn’t have to move as one. Also recon squads should never make contact with enemy by other means than directing arty on them.

Teh, I know a squad does not need to move as one, but it does need to be close enough to coordinate all the fireteams at least.

And yes, I know recon teams are not supposed to engage the enemy. Key word being ‘supposed’. Accidents happen. Including ambushes especially since the recce team is usually the ‘moving/infiltrating’ party while the defending team is usually dug in and waiting. Which makes our overload even worse since you cannot extricate at speed with 70kg on your back.

The Rk62 does prove something I always though, that the AK’s rumored lack of accuracy is due to quality control and training rather than design problems.

@Teh, yes, I got the hint “if my nickname isn’t enough of a clue for you Finland uses RK62 and RK95.”

But you also have the nifty Valmet (forgetting now the year designation for it) light MG that shoots 1000 rpm

– would have thought that is an ideal weapon for a light team disengaging under fire

– while I read that the “line infantry” has not been overly impressed by it.

However, with that one (if carried), we would not be counting the weight of 20 rounds mags, but 100 round “canvas” pouches?

– if you never come to the situation of having to use it, you can refill the team mags from those “belt pouches”?

@ Civvy,

the weapon mentioned is KVKK62 aka. light machinegun model 62. It’s being phased out in favor of PKM which has been mainstay MG for quite some time. Recon troops carry only assault rifles and selection of sniper rifles. RK has 30 round mags and yes we could feed our guns with cartridges from MG belts.

I can shoot 10 rounds 10 seconds out to 150m with 10x15cm grouping with RK62.

Best weapons for recce team to disengage is smoke grenades. In a contact those who are closest to the enemy might as well die or ditch their packs. All that weight is useless if we can’t break contact with it.

@Gravy – “Has anyone looked the number of hits on body armour in say Helmand and how many lives have been saved by its use? perhaps lighter soldiers would be more effective in pursuing the enemy and thus reduce their vulnerability.”

Back in 1948 the US army did something similar. Some select quotes below:

“The weight of body armor necessary to provide any

gain would decrease the battle effectiveness of the combat

soldier. Because analysis shows a requirement to reduce

currently prescribed combat loads carried by the soldier

and the difficulties in eliminating or reducing the weight of

present equipment, no chance is offered to include body

armor without seriously decreasing battle effectiveness.

This conflict cannot be solved by research directed only

toward the development of light weight armor materials”

“The armor helmet is a device of very great military

value… The helmet should be redesigned to provide increased coverage

over the cranial region. NO sacrifice in frontal coverage

to allow the use of sighting equipment should be made in helmets

for infantry.” [emphasis original]

Teh, you’re not telling me anything I don’t know but even with deployed smoke you still need suppression fire to disengage which is why you still bring your ammo out, not leave it back at base and bring only smoke. Shooting at the enemy is still a good way to make them keep a respectful distance.

Though we are a bit off topic, the point of overloaded infantry. And no, leaving your rifle ammo behind is not a good way to cut weight. We need to mechanize more so we can bring more equipment/food/ammo to the infantry, not make the infantry carry all the equipment at once. Basically setting up resupply points close to the squads and let them replenish their expendables from there. Lots of weight can be saved if, for example, you let an ATTC carry most of the squad’s water, LAWs, stoves, clothes, ammo, etc especially water.

Observer,

I agree wholeheartedly. Infantry that means to fight with the enemy has to have vehicles. Rifle ammo isn’t the problem, the problem is the crazy expenditure of MG rounds, AT weapons, 40mm grenades that infantry just can’t carry. It has been estimated that it takes about 15kg of AT weapons to destroy BMP including misses, malfunctions, those that are destroyed and non-destroying hits.

I wasn’t sure where to post this TD as its neither a Quad nor a Motorcycle but I found the potential applications quite interesting, especially the unmanned variant.

http://www.sand-x.com/en/

https://youtu.be/1ji2iVBgUwc

ST Kinetics had a collaboration going with Milrem in Estonia for the THeMIS but I’m not sure if the government will try to exploit the system. It does look like it has potential to me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZgl-PvdJuw

In the commercial market there is an enormous amount of effort to supply multi-functional tech intergrated into one device. The commercial stand point is a one off larger purchase rather than several devices whose sum total price is greater.The controls are in one place rather than all over the gun, a single battery type that also often that can be externaly supplanted by a single power supply or even externally rechargable.

Granted it’s all your eggs in one basket but a section/team can carry spare/s between them for the guaranteed application of Murphy’s law that happens to an individual to ruin their day.

Many of these new units include GPS, multiple external electronic links , altitude , temperature, data etc etc which could possibly supplant existing separate handheld devices. It’s a fast moving world and the right funding to the right presently cash starved company could reap massive rewards.With all the Intellectual Property Rights to the company involved and a carte blanche to sell to our allies would stimulate a LOT of effort. Just a thought.

The problem with a common battery is that they do not suit the different equipment in use.

For example, can you imagine powering a laptop with AA sized batteries?

Or using a laptop battery pack longer than an NVG to power it?

The main reason why we use so many different batteries is because the power/size requirements for different equipment is drastically different.

And I know for a fact that the reason we don’t use rechargeables is that batteries lose maximum charge after frequent reuses…and you can’t track the degradation, so if you’re unlucky, you might end up grabbing a battery that lasts, for example, 10 minutes instead of 2 hours and you won’t know until it dies on you.

Hi Obs , I get what you mean about battery types being tailored to each devices needs. I was trying to get over the point (badly) that by putting as many essential functions in one device , the smart gun sight (most developed from COTS devices ) you can reduce the number of devices carried thus battery types.

Many functions are now able to be intergrated into one device whilst acting as a battle sight can also form other functions , recording sound , vision (visible and IR ) , location , temperature, barometrics , altitude , compass , inclinometer , range finder , ballistic computer , data upload and download via multiple channels with outputs to helmet mounted displays too centralized battlefield control centers on other continents whilst receiving data to bolster the mission.

Your specialization as Recon burdens you with other kit whilst removing weight from arms to ammo load not deemed essential to your role but the more (selectable) functions and data available the more potential could be realized out of each soldiers role.

By combining functions into one device could lead to the investment by the military to a single very much better (and very much more expensive) battery type.

Don’t know how practical it is Stephan, though it sounds like a nice idea. For TI, the system needs to cool down first before using and it sucks a LOT of power, not sure if a simple gunsight has the power to do that and all the other things you want. The commercial non-cooled systems in the market tend to be cut rate jobs that have much lower resolution and range. IIRC the blocky cooled system I use has only an on paper range of 150m (human targets, large vehicles tend to be easier to spot).

I’d love for one item to do everything you said but nothing in this world comes for free, I’m just not sure if you can shove what you want in and maintain durability, performance, power requirements, size, weight, flexibility and cost.

Not to mention our service issue rifle’s scope is already inbuilt into the weapon. Hey, it was designed in the 90s before P-rails became popular. :)

The only helmet mounted display system I know in common use is a night vision monocle clipped to the helmet, the computer game type of display system does not exist, at least not yet.

https://qph.ec.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-63104ebce07e6068adb30abedbbc79a6-c

The guy on the left is using the inbuilt 1.5x scope with a clip-on M-203. The unit on the side is a kind of pseudo quadrant sight.

The middle guy is using what I -THINK- is a thermo-imager. The 1.5x scope is below.

The guy in the background is using a video camera display for looking around corners.

I’m not saying we have the be all and end all of tech but with the demonstrated size, weight, power and ergonomics constraints, I’m just not sure if what you want is practical without more sacrifice than it might be worth.

If the new 6.8mm developments in the USA come to fruition, there may be some opportunities to take a new direction. This new direction would require a change from weight of fire, to accuracy of fire. With the availability of multi-spectral imaging together with image intensification and magnification, it should enable more accurate engagements at longer range. If every shot could be made to count, in wide open engagements, then the carried ammunition load might be reduced.

Suppressive fire is also more effective when aimed, rather than; ‘spray and pray.’

Each light infantry rifleman could, effectively, become a marksman and the benefit would be most evident in the wide open spaces.

Rifle sound suppression will also become a; ‘must have,’ to assist unit voice communications and enable surprise.

Individual multi-spectral imaging will, most probably, have a significant impact on every battlefield and that weight penalty will need to be factored in. Sidestepping this issue could have painful ramifications.

When paradigm shifts occur it is necessary to invest, in order to stay in the frame.

Thank you there is a fine accolade to the Xtract SR stretcher here. For more information please see http://www.tsgassociates.co.uk

Coming from a NI veteran, it would be good to see in such a report what the weight is made up of, depending in which theatre it is