Continuing the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) series, this one looks at power systems, weapons, and protection.

Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) — Electric Drivetrains and Alternative Fuels

For the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV), it would seem natural that electric propulsion and alternative fuels would be a component of the wider requirement set.

The British Army has completed several projects focusing on electric and hybrid vehicles, aiming to reduce fossil fuel use and enhance sustainability.

These have involved the Foxhound, Jackal, and MAN SV, funded by a £9 million programme led by Defence, Equipment & Support.

Announced in 2022, the Battlefield Electrification Approach outlines a decade-long plan to increase the use of batteries, hybrid electric drives, and other technologies across the vehicle fleet. This aligns with the Future Soldier vision, emphasizing enhanced stealth capabilities (reduced thermal and noise signatures) and mobility over challenging terrain.

Power export, extended range with hybrid systems, and silent operating are obvious advantages.

Reduced heat signature and maintenance, reduction in costs from braking consumable another (the electric drivetrain can handle most normal braking) and improved off-road performance are less obvious.

Given the increasing demand for energy, as the Army becomes more connected and distributed, practical demand will drive electrification more than any ideological commitment to Net Zero.

Retrofitting diesel vehicles with electric or hybrid power and transmission systems is certainly possible, and there are kits for a number of the potential contenders

Tembo in the Netherlands markets a Land Cruiser kit, for example.

In 2023, Babcock was awarded a contract to convert four British Army Land Rover Defenders to all-electric, partnering with Electrogenic.

This project, known as Project Lurcher, involved integrating a drop-in kit and modified battery system to test the vehicles in battlefield scenarios, assessing performance over steep terrain, wading, and towing.

With a 63 kWh battery, the Tembo Land Cruiser 70 conversion lists a range of less than 125 miles (ca. 201 km). The diesel version of the same vehicle has a range of three times that, and instead of a 1-2 hour recharge, the diesel tank can be refilled in less than 2 minutes.

Electrogenic also makes drop-in conversion kits, approximately 150 miles (ca. 241 km) range for a Land Rover Defender.

However impressive, diesel is still difficult to beat for energy density and refill times, and if we want more range than the most common drop-in conversion kits offer (circa 100–125 miles (ca. 201 km)), a dedicated design might provide better options.

Munro in Scotland makes one such vehicle, with an 85 kWh battery, the M280 model can do approximately 200 miles (ca. 322 km).

Range and recharge time are the Achilles heel of battery only vehicles, especially in a defence context where access to high-capacity mains power is not assured.

Range can be extended with Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), and these are becoming increasingly used in the building industry.

They have forklift pockets and typically range in power capacity from 30 kWh to 250 kWh, with a 100 kWh unit weighing circa 1,500 kg.

Optimised for vehicle fast charging, the Zapme is a 50 kWh unit.

A single unit weighs 800 kg and is 1886 mm x600 mm x 1100 mm (Length, Width, Height)

At a smaller scale, the Solus Kratos is a ‘jerrycan of power’

The video certainly looks interesting.

These solutions are improving all the time, but they still present risk and technology maturity issues for the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV).

Going electric will require a long-term investment across multiple defence lines of development, and no small amount of change across wider defence vehicle and fuel capability areas.

Hybrid solutions could be a lower risk option for LMV, and provide a bridging capability to full electric.

Diesel-electric hybrid vehicles are not common in the consumer market, eclipsed by the rapid rise of petrol-electric hybrids, plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) with petrol engines, and fully electric vehicles (EVs).

For defence markets, petrol is not favoured, and diesel, now universal.

Based in London, Fering has designed and built a diesel-electric hybrid vehicle called the Pioneer/Pioneer X, aimed at utility and defence markets where range is a limiting factor in the adoption of EV’s.

With a multi-fuel or hydrogen engine, and a 20 kWh Lithium Titanate Oxide battery, it has a whopping 7,000 km range, and can provide 60 kWh of power to onboard or offboard systems.

At the other end of the scale, Edison Motors in Canada is creating diesel-electric hybrid trucks for the heavy haulage and forestry sector.

They have reported a 1,000 mile (ca. 1,609 km) range on 120 litres of diesel.

Synthetic and biofuels, and hydrogen, do not seem to have garnered much publicity, but hydrogen electric is another option worthy of consideration.

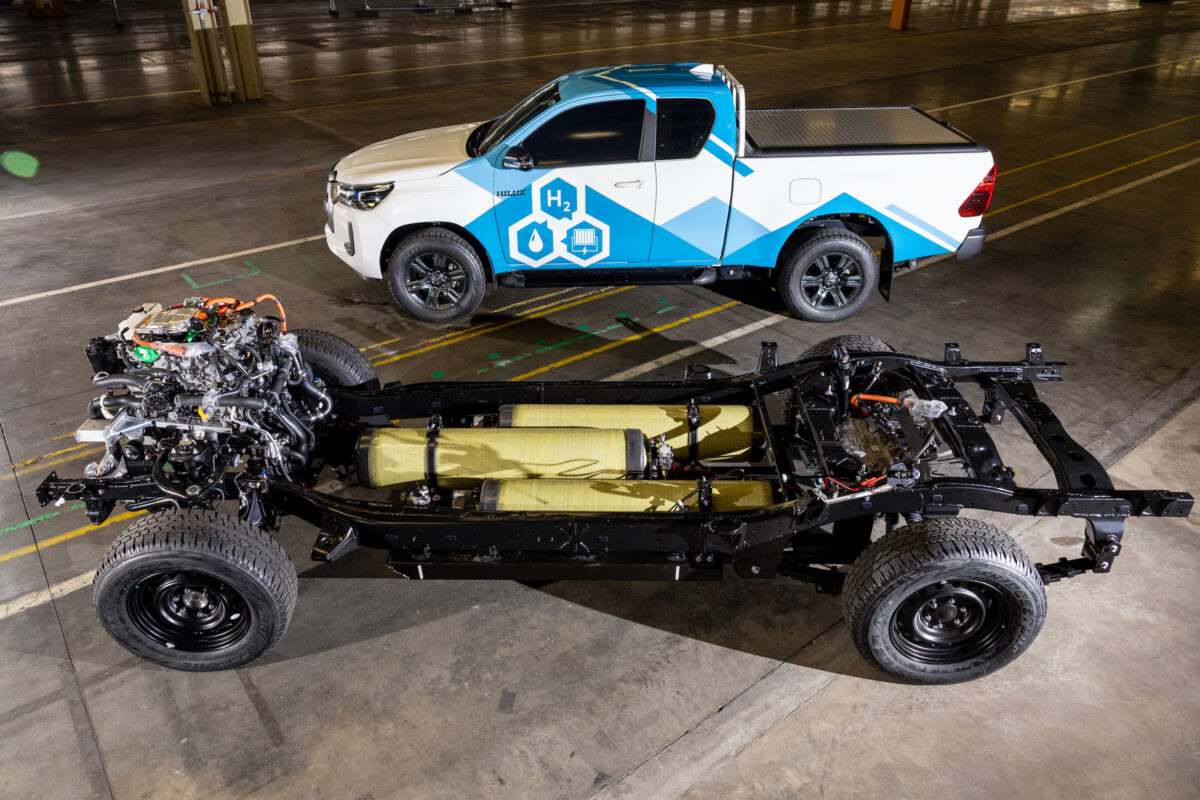

Toyota revealed a British built hydrogen electric hybrid Hilux pickup in late 2023, developed with Ricardo, ETL, D2H Advanced Technologies and Thatcham Research.

Three high-pressure fuel tanks are used with a hydrogen fuel cell and battery system, providing 356 miles (ca. 573 km) of range.

JCB are also investing significantly in hydrogen technology, developing generators, hydrogen combustion engines and engineering plant.

JCB and Toyota have partnered and shown their respective products together.

The French Army, and several others, have also been trialling hydrogen fuel cells and associated technologies.

Before anyone mentions the Hindenburg, there have been a handful of interesting studies into fire and explosion hazards with hydrogen cylinders, they are much safer than many assume.

While they may not be as emission-free as fully electric vehicles, Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEV’s) strike a practical balance between efficiency, convenience, and performance, especially range.

Another aspect of electric vehicles is -48v DC.

48v DC provides three main benefits.

- Improved Efficiency: A 48V system allows for higher power delivery with lower current compared to traditional 12V systems. Since power (P = V × I), increasing voltage reduces the current (I) needed for the same amount of power. Lower current means less energy loss due to heat (I²R losses) in wiring and components, improving overall efficiency.

- Support for Electrification: Modern cars increasingly rely on electric components such as hybrid systems, regenerative braking, turbochargers, and advanced driver-assistance systems. A 48V system can handle these power-hungry features more effectively than a 12V system, which is limited to around 3–4 kW before wiring and efficiency become problematic.

- Smaller, Lighter Wiring: With lower current requirements, 48V systems can use thinner, lighter wiring harnesses. This reduces vehicle weight, improves fuel economy, and frees up space, which is especially valuable in compact or electric vehicle designs.

The move to 48v DC is being accelerated by Ford, Tesla, and BMW, with an ecosystem of suppliers like Valeo, NXP, MTA Automotive, Eaton, Infineon Technologies, Prodrive, and BorgWarner.

In a defence context, it could also be used to finally eliminate 240v AC devices from small CP’s and support 48v telecommunications equipment (common in the civilian telecommunications sector). Extended Power Range (EPR) USB 3.1 Power Delivery also supports 48v, at approximately 240 watts, although anything over a few metres would need larger cables.

48v to 24v converters are widely available to support legacy communications equipment and other systems, but as 48v supports significantly higher power levels than 24v, more powerful equipment such as drone jammers can be used on the same circuit.

NATO Generic Vehicle Architecture (NGVA), standardised under STANAG 4754, provides for 48V DC systems as part of its framework for military land vehicles.

The key standards for 48V DC automotive systems include ISO 21780 (and its UK adoption BS ISO 21780), VDA 320, NGVA (STANAG 4754), and supporting EMC/safety standards like CISPR 25, ISO 26262, and MIL-STD-461. These ensure 48V systems are safe, efficient, and interoperable across civilian and military applications.

BS ISO 21780

This document covers requirements and tests for the electric and electronic components in road vehicles equipped with an electrical system operating at a nominal voltage of 48 V DC.

This includes the following; general requirements on 48 V DC electrical systems;, voltage ranges and slow voltage transients and fluctuations (not including EMC).

For the UK, BS ISO 21780 and NGVA are particularly influential, guiding both commercial manufacturers and MoD programmes

With a fast approaching 2030 and the general technical and conceptual maturity of electrical vehicles and alternative fuels in a defence context, it might be too risky to electrify Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV). But neither can LMV ignore the work done, investments already made, general trends, and advantages on offer from electrification and alternative fuels.

Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) — Weapons and Protection

The only variant with a weapon is the LR WMIK replacement, called the Tactical Mobility Variant (TMV)

The LR WMIK was developed in the late nineties and over several iterations has evolved into an effective weapons carrier for infiltration forces, light role cavalry, and specialist users. At just over 4 tonnes, it is heavier than most other Land Rover variants, due to additional protection, electronics, the weapon mounts, and ammunition stowage.

SF type weapon carriers are literally ten a penny, almost every one of the candidate vehicles has one.

Pintle mount, ring mounts, GPMG, HMG and GMG seem the norm, together with ECM, communications equipment, protection, and stowage all seem common.

The main question for the Tactical Mobility Vehicle is why?

All the other variants are not meant for direct engagement with enemy forces, and in an age of FPV’s, guided missiles, large calibre automatic weapons, and drone dropped munitions, are we simply asking for trouble?

I think this type of vehicle is increasingly specialist, for SF and 16AAB perhaps, rather than a component of the wider Field Army, but that is just an opinion.

One could certainly see the payload of the more conventional Utility Variant being used for a tethered drone, loitering munitions, or as a carrier vehicle for air defence teams using HVM/LLM Martlet.

Another interesting debate is whether a Remote Weapon Station would provide greater utility than a pintle or ring mount.

As usual, pros, and cons.

Training and cost for RWS would be significant, especially when compared to the cost of the base vehicle, and a loss of close in situational awareness would be negatives. No reversionary modes and increased maintenance also.

But the ability to accurately fire on the move, and to greater ranges, with excellent optics, would be advantageous.

We might even consider using an RWS with a 20-30 mm calibre automatic weapon, either for ground targets or against drones and FPVs, like the Northrop Grumman M230LF shown in the image below.

As usual, it would come down to the role and cost.

It would also be worth exploring if we could get one under 3.5 tonnes, or with an ability to remove additional armour for training.

There is also a Light Mobility Vehicle (LMM) variant that requires STANAG Level 1 protection, called the Enhanced Protection Vehicle (EPV), with one driver and three passengers.

Difficult to see if this is an LR Snatch replacement, or something different.

The Foxhound notionally replaced most of the Snatch role, but there might be some persistence for a lower protection level vehicle for use in civil disorder roles, although this seems unlikely.

There might be some crossover with the Civilian Armoured Vehicle (CAV) programme.

The MoD recently advertised a support contract that would support;

- Existing protected vehicles, including fully armoured Toyota Land Cruiser (LC) 200 series.

- Partially protected vehicles, such as the Toyota Land Cruiser 79 series.

- Future procurements, including light to medium commercial 4×4s, vans, and cars.

Even if retained, the LMV EPV could draw on the many capabilities of Babcock and others.

Another weapon we might consider is the 105 mm Light Gun

The Light Gun is currently towed by Pinzgauer, and there have been trials using Jackal.

Whether we end up staying with the Light Gun

Or going with mortars

There are options.

The armed variants remain open to some debate, and it is not unreasonable to suggest that for specialist users, maintaining commonality with the rest of the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) might constrain options and limit choice. The protected variants might also be close to the CAV programme.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I think the proposed LMV EPV variant is a replacement for the RAF Regiment's TUM Enhance Protection Vehicle (EPV CAV 100), which were designed for Airfield Protection. In this role they shouldn't be exposed to IEDs, however in Ukraine FPVs have been used to attack the underside of vehicles which may render the concept moot.

Any open sided vehicle must be very prone to drone attack

Looking at the RWS on pedestals, I've often wondered if it would be more space efficient to automate a ring mount instead. It would probably cost a bit of slew speed and elevation arc of the gun, but if it was OK for a ring mount in the first place?

I imagine that the Tactical LMV will be a prime candidate for a lightweight / low cost RWS. Mission fit maybe, but has to be on the chalkboard fr consideration.

"Any open sided vehicle must be very prone to drone attack"

Watching video from the Ukraine I am constantly amazed about how doors, windows etc. are left open. Reminds of the old adage that not all concealment is cover but all cover is concealment. Covering an opening my not stop an explosive. But covering may dissuade an operator from trying to enter a structure.

Modern hyrdrocarbons are too fuel efficient and modern batteries and 'alternators' still too heavy to make hybrids or EV's a serious proposition. Hydrogen? In the field? Really? Nah………