In this third part of the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) series, payloads, logistics, and fuel.

Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) Payload Challenges

The Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) faces some noteworthy payload challenges.

In Part 1, I explained the trend towards higher kerb weights in modern vehicles and the hard upper limit imposed by the max 3.5 tonne Gross Vehicle Mass (GMV) of a vehicle that can be driven on a B/BE licence.

Contemporary civilian vehicles that one might ordinarily consider for the role include the Ford Ranger, Isuzu D-Max, and Toyota Hilux, to name but three.

| Vehicle (Double Cab) | Kerb Weight (kg) | Gross Weight (kg) | Payload (kg) |

| Isuzu D Max DL20 | 1,995 | 3,100 | 1,105 |

| Ford Ranger XL | 2,053 | 3,270 | 1,142 |

| Toyota Hilux | 2,105 | 3,210 | 1,015 |

SUV and Station Wagon type vehicles include the Toyota Land Cruiser, Mercedes G Class, and Ineos Grenadier.

| Vehicle (5 Door) | Kerb Weight (kg) | Gross Weight (kg) | Payload (kg) |

| Toyota Land Cruiser | 2,205 | 2,990 | 740 |

| Mercedes G450 | 2,734 | 3,200 | 466 |

| Ineos Grenadier | 2,678 | 3,500 | 747 |

For clarity, these are civilian vehicles, but they are useful to illustrate the point.

The requirements for the General Purpose Vehicle (GPV) variant indicate a requirement for a driver and three passengers. These, and other things, must be taken from the ‘payload budget.’

- 4 soldiers at 180 kg each, including their individual weapon(s) and ammunition, water and rations, and other personal; equipment

- Complete Equipment Schedule (CES) including tools

- Cam Nets and, potentially, C-UAS mesh

- Additional alternator and wiring for 24v

- Roll Over Protection System (ROPS)

- Radio clip in kit

It is difficult to see that coming in at less than 900 kg.

Where space exists, especially for a pickup truck, there is a danger it will be filled and go over the plate weight, inviting safety and legal issues. Front axle weight rating is also a concern for many similar vehicles.

The Army could trade away the 4 seat requirement, and some of the more defence oriented vehicles have fewer creature comforts to reduce kerb weight, but this is still a difficult challenge.

The C2 variant has even more difficult weight problems.

Not only does the requirement specify the same number of seats as the GPV, but it also has an enhanced radio fit, batteries, and work space for three personnel.

The Utility Variant is also puzzling, the initial information indicates the same common base platform as the GPV and C2, but an additional payload of between 1 and 2.5 tonnes.

This 2.5 tonne upper limit for the LMV Utility Variant (UV) is close to the 2.2 tonne payload of the RB44, and the RB44 was no small vehicle, certainly above 3.5 Tonnes GVM.

No doubt all will become clearer as more information is released, but weight and size across the variants is a challenge, some more than others

Pallets, Boxes, or Both

Many of the variants will only be used for transporting personnel and their equipment, but others will need to carry a multitude of defence stores and equipment.

Payload requirements need to be based on organisational reality and the most likely use cases. Since this vehicle would not normally be used by RLC transport squadrons, palletised loads are less likely to be transported.

A CQMS or SQMS carrying out a mixed water, rations, and ammunition replenishment or delivering defence stores to build a battle trench is a more common activity than moving a pallet of ammunition of the same type.

Therefore, it is likely that Peli ISP2/Amazon cases, Zarges boxes, pickets and wire, cam nets, telescopic communications masts, and individual boxed items will be the norm.

Even so, pallets could still be used for the Utility Variant (UV).

Assuming the Utility Variant (UV) ends up being larger, and above 3.5 tonnes GVM, a typical baseline could be the NATO pallet (1m×1.2m).

Examples…

A single Javelin ATGW (in its plastic container) pallet has six missiles.

These can be double stacked, so on a vehicle that has space for two pallets, a total of twelve missiles can be carried, on a total of four pallets. A single pallet weighs approximately 620 kg, four would be 2,760 kg in total, including the pallet itself.

This would be slightly over the UV upper limit.

The BAE Lightweight Cartridge provides for palletisation, a four box layer pallet containing 86,400 rounds of 5.56 mm weighs 1,166 kg, compared to 1,322 kg for a conventional design. A two pallet load would contain 172,800 rounds at a total weight of 2,332 kg.

Slightly under the UV upper limit.

Depending on the ration type, a single pallet will generally provide 350 rations and weigh approximately 800 kg. Two pallets providing 700 24 hour rations for a total weight of 1,600 kg.

Water is typically not provided at this scale using bulk tankers, but a standard 20L jerrycan weighs 24 kg full. Commercial 0.5 Litre plastic bottles are commonly available in pallets of 1,800, 900 Litres, just under a tonne.

These are a handful of examples, but the weights for a couple of pallets of typical commodity items ranges from a tonne to three tonnes. Therefore, two pallets and 2.5 tonnes seems a flexible and appropriate requirement for both weight and load bed space for the Utility Variant.

While most variants would not likely carry palletised loads, the Utility Variant should have the space to carry two standard NATO pallets, recognising that some combinations might exceed the 2.5 tonne payload requirement.

Beyond the Basic Pallet

Assuming that the ‘pallet footprint’ is still the basic unit of measure, there are many practical options to expand their utility.

A simple box pallet would work well for loose items.

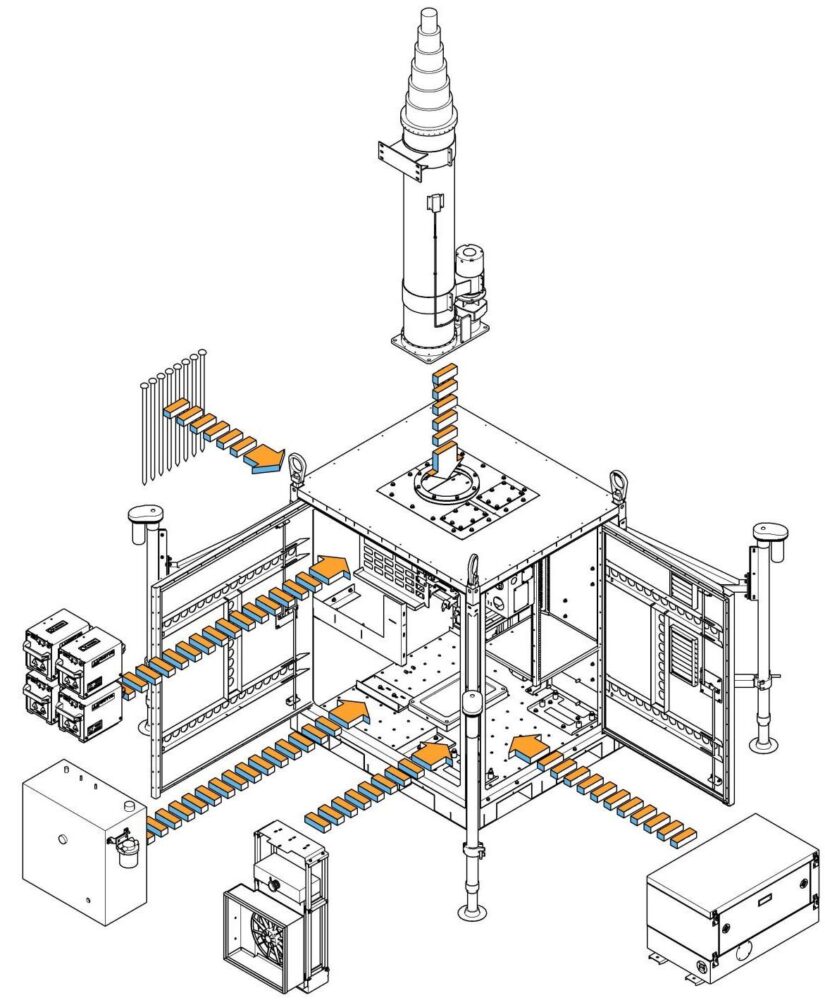

A few years ago, a company called Dytecna developed a pallet-based electronic equipment shelter called the Cube, with the footprint of an EUR2/NATO pallet.

The Cube was designed to be adaptable, with options for different types of electronic equipment, integral power systems, and telescopic masts.

This could even be an alternative or complement to the Command Vehicle, and one could imagine a plethora of electronic systems in such an enclosure.

The Hammerstone D-JMILS MIL STD 3028 JMIC is a modular stacking container that locks top and bottom to form a single unit.

JMIC internal and external dimensions have been optimised for transportation through the military and civilian supply chain, and their internals can be infinitely adapted using various boxes, shelves, dividers, drawers, and spacers.

Another system is from Shark Cage, their Lockers, Baskets, and Wheel Cages could be equally useful.

Both systems are optimised for efficiency and ease of transport, some are dimensionally optimised for ISO container transport, others for aviation pallets, the 2.29m (longest dimension) Spacesaver Rapid Readiness box, for example, is optimised for ISO containers.

It is easy to see how any of these systems could be used for everything from REME Equipment Support detachments to ISTAR Groups and Drone Teams in light role units.

Even something as simple as a non-standard pallets box like a 2.16 m × 1m Dollav SL2160 has value, it is cheap, and would allow items like tools, pickets, and defence stores to be neatly packaged and moved through the supply chain.

These longer pallets can also be used to carry liquids, the Lifeliner CUBE shown below.

Pickup trucks can also be fitted with pallet decks that provide space underneath for drawers, boxes, and other equipment.

We could also look at the dimensions of smaller vehicles and engineering plant, a quad bike perhaps, or a set of hand tool boxes, a plate compactor, or a small generator/Battery Energy Storage System (BESS)

Width

Start with 1.2m for a NATO pallet and bulk bag, but expand to 1.3m and many other things come into play.

You will be able to accommodate a JMIC, a Container Delivery System skid board, a good spread of shark cage baskets/lockers, two of the four Rapid Readiness Boxes, a typical Quad Bike ATV, and most small generators.

1.4m, High Velocity Missiles across the width, and a number of other Shark Cage products, plus a mortar barrel.

1.6m wide means two Euro pallets, a selection of Shark Cage products widthwise, and even some small UTV’s and vehicles like the Polaris MRZR.

1.8m, pickets and telescopic masts, larger Zarges and Peli ISP2 cases, and many UGV’s. 1.8m wide also theoretically allows two side by side in an A400M and internal carriage in a Chinook.

2m, a TRICON and QUADCON container, and two NATO pallets side by side along the short axis.

Length

Generally, it is easier to achieve longer load beds than wider.

Again, start with 1.2m and a NATO standard pallet will fit.

Double that to 2.2m, two of those same pallets, and most of the Shark Cage products, a TRICON, and two JIMC’s on the short axis, a Doll 2.16m pallet (for all the defence stores, masts, and missiles), most trail bikes, and a small UTV.

3 meters still means two JIMC’s and two NATO pallets on the long axis, but three of the latter on the short axis, all the Shark Cage and Rapid Readiness products. Three 1 tonne bulk bags, a double CDS pallet, an ISU90 aircraft container, a QUADCON and TRICON container, a BICON container with 50 mm overhang, fuel/water tanks, and even a Polaris MRZR with 160 mm overhang.

We might not have any of these alternative storage and transport systems in service right now, but by carefully examining the various options available, load bed size requirements can be developed that provide maximum flexibility and future proofing.

Enhanced Cargo Handling

It is reasonable to assume that a telehandler will be available at the loading location for the Utility Variant (UV), but it is less likely that one will be available at the destination.

At the upper end of the Utility Vehicle requirement, or if there is scope for a larger payload vehicle, there may be benefit in having a mechanical system for rapid unloading, or loading.

The three main options are a skip loader, a hook lift, or a hydraulic crane jib.

Small skip loaders are common for low capacity skips and are often used in urban areas.

Except for the KMW Mungo, less used in a defence context.

Mungo is a militarised version of the Multicar M30 municipal maintenance vehicle. The skip loader design was chosen to reduce the height so it could fit inside German CH-53G helicopters.

Hook lifts that are designed for vehicles with less than 3.5 tonnes GVM are not common, but they do exist, often used for cheaply moving unloaded skips. Palfinger and HIAB Multilift are two of the more widely used manufacturers in the UK.

The Swiss company Roelli makes a product called the X-Rack.

The X-Rack is designed for smaller vehicles, such as pickup trucks and small chassis cab vans.

They have a well-developed range of small plant platforms, tipper bodies, and equipment trays.

The system is also capable of being used to load and unload pallets and bulk bags.

The equipment itself is 650 kg in weight, and has a maximum lift capacity of 1,250 kg.

Hiab, Palfinger, and many others also make small hook lift systems.

The Achleitner Carrier, for example, comes in a double cab version with a hook lift, as per the image below.

The image also shows a retractable load bed cover to provide limited protection and concealment.

The long since out of business Ovik’s company looked at this concept a while ago with their Chameleon vehicle, based on an Iveco Daily 4×4.

At full scale, flat racks are designed to fit inside ISO containers, such as the M3 Container Roll Out Platform (CROP) in the image below.

Although the CROP width of 2.3m is too wide for LMV to allow two JMIC across the width, a half-length and reduced width version would still be useful. The vehicle would be able to carry two JMIC on the long axis, a range of Shark Cage products, and many items of small plant, vehicles, and equipment.

Skip loaders add less height than hook lifters and keep the payload level while loading and unloading, but they weigh more than hook lifters.

Although hydraulic jib loader cranes are not as fast as either skip or hook loaders, they are flexible and lighter.

They can be mounted forward or to the rear, with a range of load and reach options.

A tail lift would be another option, but they usually limit mobility.

Finally, an unusual system from the USA called the LiftPro, the whole assembly weighs 1,600 kg.

When the forklift mechanism is not in use, it is possible to use the load bed normally.

And can tow a gooseneck trailer.

But it can transform into a self-loading forklift with a capacity of 2,040 kg.

Although limited to one pallet or load platform, it eliminates the need for a telehandler at either end of the journey. It can lift from a truck bed or the floor, and drop the load off at the destination.

I really like this system, although it is not viable for the sub 3.5 tonnes GMV variant.

Load handling systems can be extremely useful, especially where speed is an issue, or loads exceed manual handling limits. But they will all add weight, cost, complexity and through life support issues. None of these are likely to be of any utility on the smaller variants.

Demountable Bodies

All the same benefits as Boxer modularity can be realised by LMV.

While some Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) roles could be fulfilled by using demountable bodies, there may be some potential in doing the same for variants.

Many innovative possibilities can be provided by taking a modular approach, similar to Boxer.

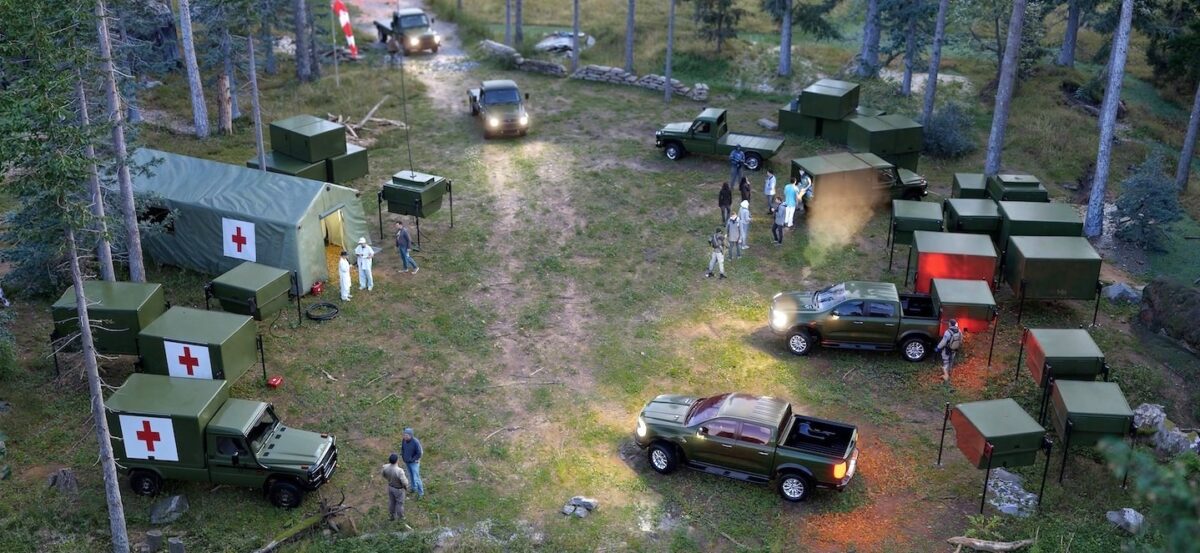

The ‘payload module’ could be a load bed, an ambulance body, or a command and control space.

When the vehicle is in a maintenance period or damaged, the module can be transferred to another, ensuring continuity of availability and reducing costs.

Whilst not quickly demountable, tray backs are available from most OEMs, and there is an active after market for them.

Many designs are available, this example from Pickup Systems has an equipment locker.

Another example of this is shown below, with a fully flat load bed, storage lockers, and load restraint rails.

Slide out trays can also be integrated.

Shelters can be connected to the float load area.

Or, alternatively, tool storage.

Other similar options can increase the adaptability of a flat load bed or chassis.

For pickup truck style vehicles with no clear flat load bed, the general approach can still be used.

These would not need any of the enhanced cargo handling systems described above.

Jacks would be enough.

Storm Defence in Norway make something similar, called the RADS (Rapid Adapt and Deploy System).

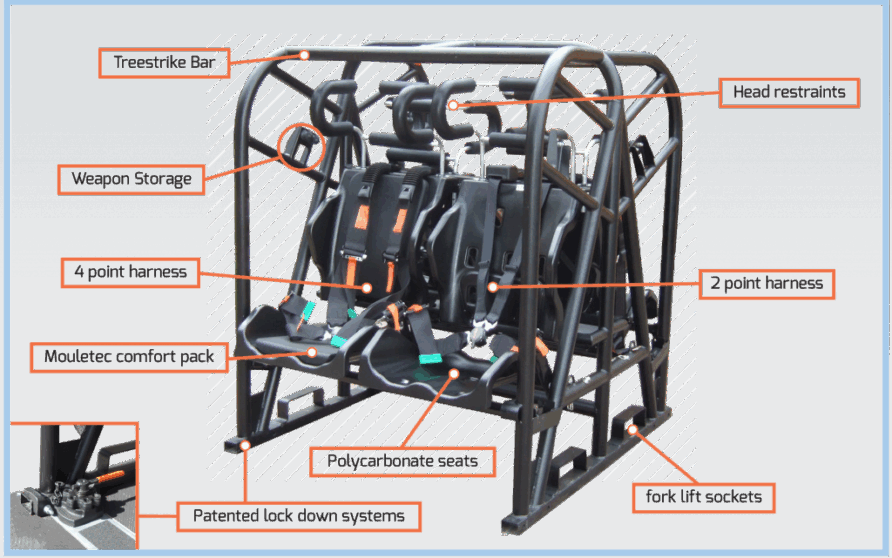

VSS and Protek in the UK make ROPS modules that could be fitted to a flat load bed module to provide personnel seating, as do many others.

The Weatherhaven TRECC, described in the previous post, can also be mounted on a vehicle load bed.

In previous years, we might have been limited by the 2.74 m cargo hold height of the C-130, but now that they are no longer in service, the 3.85-4.00 m A400M cargo hold height is much more permissive.

As long as the load bed height of the base vehicle is no more than 1.2m high, a demountable shelter with the same height as a standard ISO container can be carried whilst still maintaining air transportability.

There is a lot of potential with demountable bodies, possibly including C2 and Ambulance, alongside Utility, Equipment Support, and others.

Some could have lightweight armour, and they could be equally carried by other vehicles and trailers, high mobility load carriers for example.

All of these systems are based on clear deck vehicles, but because I am including AWD vans in this series, they can also be used with demountable payloads.

The Germany company, PlugVan, manufactures logistics, leisure, and industrial ‘modules’ for use with vans.

And, no doubt, could be adapted for defence requirements.

Whilst it may seem excessive, adopting a Boxer like approach to payload modules could improve flexibility and reduce overall costs

Beyond 2.5 Tonnes Payload

There isn’t a requirement in the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) requirements for a payload of beyond 2.5 tonnes, but should there be?

Going back to OUVS

The OUVS Large vehicle requirement specified a payload of 4 to 5 tonnes.

This would require a re-think on the use of the MAN SV 6 Tonne, but as many have noted, it is too big and heavy for many roles, and doesn’t have enough payload for others.

There might appear to be little logic in disposing of a 6 tonne payload vehicle for around £20-30k and purchasing a lower capacity vehicle for triple that. However, there might be good arguments in terms of through life costs, and operation in urban areas or other limited terrain.

Definitely one for consideration as it would allow larger vehicles like the Mercedes-Benz Unimog, Tekne Graelion, or better use of the larger 6×6 pickup trucks, and industrial/agriculture vehicles.

In the following posts, I will include these larger vehicles that could meet the OUVS Large payload, whilst accepting that they are not in the LMV requirements.

Although not in the LMV Requirement, I will look at options for going beyond 2.5 tonnes payload in the following parts of this series.

Fifth Wheel and Trailers

As discussed in Part 1, trailers can be a double-edged sword, reduce mobility, and especially for some roles like Command and Control, an impediment to rapid movement.

Opening rear doors is often prevented by trailers when hitched.

On the other hand, now that BE is automatically provided, it allows 3.5 tonnes to be towed by a Light Mobility Vehicle. If we assume a trailer weighs a tonne, the balance of 2.5 tonnes meets the upper objective of the LMV Utility Vehicle (UV)

A suitable trailer could be used for concertina tape or small plant.

The Dutch company Pallet Trailer produces many models for road use, the largest being able to lift and carry a 1.8-tonne pallet or JMIC.

And even things like the Workfloat ferry and work platform.

They can have demountable bodies.

Campwerk developed this model for the Dutch Korps Commandotroepen

And this, from Offroad Designs in Australia, has a payload of 2,200 kg and an empty weight of 650 kg.

These are just a random selection, but there are many excellent trailer manufacturers in the UK, like Towmate, Brian James Trailers, Ifor Williams, Nugent, and Graham Edwards, to name but a few.

Trailers are available in an almost infinite array of variations, even for carrying a GMLRS pod.

Gooseneck trailers are popular in the USA but much less so in the UK and Europe. Fifth wheel van conversions are more widely used, although still uncommon, and many would be over 3.5 tonnes so needing a higher class of licence.

They are aimed at the BE licence sector, and for road use only. These might be useful for transporting Quad Bike ATVs and similar, which don’t weigh much but take up a lot of space.

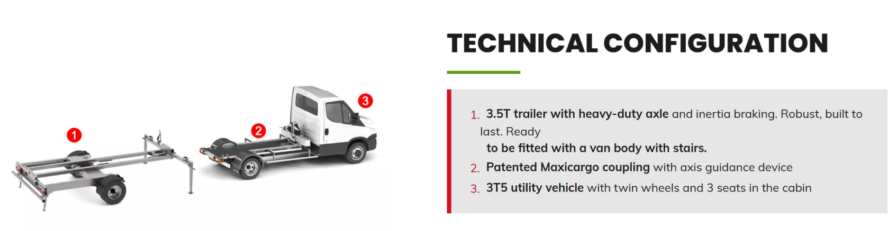

There is also a road only market segment designed to better exploit the BE market, using close coupled trailers.

Maxicargo and BE Combi are two example manufacturers.

They both use modified vans as the tractor unit, using a sub frame, braking and air system, and a fifth wheel coupling.

With a 3.5 tonne tractor unit and a 3.5 tonne trailer, they are coupled together to form a single vehicle, still drivable on a BE licence.

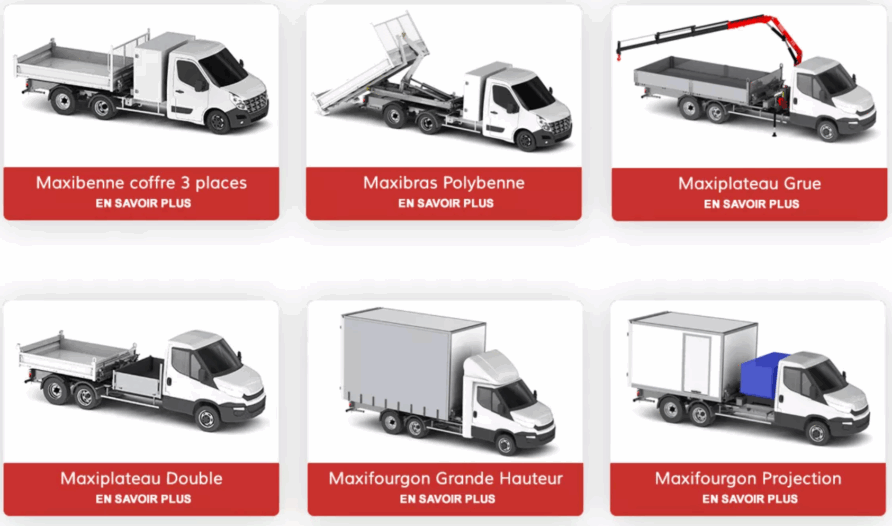

This is a practical and innovative solution.

With various vehicle body and equipment options.

But I am not sure if this could be translated into a higher mobility off-road design like an Iveco Daily 4×4 or pickup truck, or whether there would be additional regulatory obligations.

Interesting approach, though.

Whilst not without their issues, trailers can provide a meaningful uplift in payloads, but for some roles, they reduce mobility to such an extent, we should question their use.

Recovery

Finally, there is little capability for REME units to recover this type of vehicle without resorting to the large SV Recovery Vehicles or armoured vehicles.

Certainly, and Equipment Support variant could make use of integrated equipment storage, a compressor, and hydraulic jib crane.

But would a more conventional underlift recovery system be useful, even if not possible on a 3.5 tonne GVM vehicle?

For an AWD van, a stowable vehicle recovery system, like this from J+J Conversions in Hampshire would be a space saver.

And when stowed in the van.

EKA in Northampton are the go-to UK manufacturer for this application, I am sure they could do something with an LMV size vehicle.

Not on the LMV shopping list, but recovery options could reduce the need to use the large MAN SV Recovery Vehicle and provide greater flexibility for LMV users.

Summary and Next in the Series

The logistics and payload components of the Light Mobility Vehicle may seem less important than the other more numerous types, but with some careful design choices and investment, there could be a considerable upside.

Before getting into the individual vehicles, the next post in the series will cover power and fuels, protection, and weapon options.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.