The British Army’s Land Rover and Pinzgauer vehicles are to be replaced by 2030 by a group of vehicles called the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV).

In this series, I examine the issues and requirements that might shape the future vehicles and describe a range of options that might meet them.

History

The two vehicles that need replacing are Land Rover and Pinzguer.

Land Rover

Since the late 1940s, the iconic Land Rover has been a cornerstone of British Army operations.

Wherever the British Army went, Land Rovers went too.

Land Rover 90 and 110 entered service with the British Army in 1985, mostly in general service and fitted for radio variants. The name Defender was added in 1990.

Soon after, specialist types entered service; battlefield ambulance, Snatch patrol vehicle, Rapier towing, and special forces.

On April 1st, 1997, the first Defender XD Wolf (Truck Utility Light High Specification / Truck Utility Medium High Specification) entered service, with the 300TDi engine and an entirely new design from the older 90/110s.

| Feature | Land Rover Wolf 90 (TUL HS) | Land Rover Wolf 110 (TUM HS) |

| Engine | 2.5L 4-cylinder TDi, turbocharged | 2.5L 4-cylinder TDi, turbocharged |

| Transmission | 5-speed manual, 2-speed transfer case | 5-speed manual, 2-speed transfer case |

| Dimensions | 90-inch wheelbase, compact design | 110-inch wheelbase, extended for utility |

| Roles | Light utility, reconnaissance | Medium utility, WMIK configuration, Command Post (FFR) |

| Entry into Service | 1996 | 1996 |

All of them were in service by the end of 1998, and they didn’t mess around then.

The existing Land Rover Battlefield Ambulance, based on the Defender 130, weighs 3.7 tonnes, and is fitted with an insulated body, four stretcher racks, and various medical stowage bins and equipment. A couple of different models were produced and some also available in Winterised/Waterproof variants.

Since then, many have been modified and disposed of, but they remain the most numerous vehicle in the British Army. All the Left-hand Drive (LHD) variants have gone.

Pinzgauer

In July 1994, the British Army purchased 394 Pinzgauer vehicles, designated as Truck Utility Medium [Heavy Duty] (TUM [HD]), primarily to transport the 105 mm Light Gun and ammunition.

These were initially 4×4 soft top models.

As part of the Invitation to Tender LV2a/088 issued in late November 1991, a minimum payload of 1200 kg was defined.

The Pinzgauer 716M outperformed competitors such as the Land Rover Defender 110 in trials, particularly due to its dimensional fit for the TUM [HD] category, with a maximum length of 4,800 mm.

Over time, the Army expanded its use and quantities to include hard top variants, such as those fitted for radio (FFR), and later introduced 6×6 versions.

These were employed in specialised roles, including ambulances, Sampling and Identification of Biological, Chemical and Radiological Agents (SIBCRA), High Velocity Missile (HVM) system carriers, support for the ASTOR surveillance system, and Watchkeeper.

| Feature | 1994 4×4 TUM [HD] Soft Top | 6×6 Variants (General) |

| Engine | 115bhp (85kW) VW 2.4L diesel, turbocharged, intercooled | Varied, including EURO-3 compliant 2.5L TDi (post-2002) |

| Transmission | Five-speed ZF manual, two-speed transfer box | Similar, with upgrades for heavier loads |

| Dimensions | 4,480 mm L × 1,800 mm W × 2,045 mm H, 2400 mm wheelbase | Longer, GVW 4950 kg vs. 3850 kg for 4×4 |

| Roles | Prime mover for 105 mm Light Gun, ammunition resupply | Ambulances, SIBCRA, HVM, ASTOR support, gun towing |

| Entry into Service | Early 1995 | Varied, from late 1999 (ambulances) to 2008 (ASTOR) |

In early 2007, a protected 6×6 version called the Vector was introduced to enhance patrol safety in Afghanistan.

However, it faced significant criticism for unreliable suspension, poor protection against improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and limited under-belly armour, soon leading to its withdrawal from service due to these operational shortcomings.

I am not sure if the RAF Pinzgauer ambulances are still in service.

The remaining Pinzgauer are primarily in specialist roles, such as 105 mm Light Gun support.

RB44

Although no longer in service, RB44 is relevant to discussion.

A replacement for the 1 tonne Land Rover, the RB44 was manufactured by Reynolds Boughton, leveraging the chassis and cab of the Dodge 50 Series, a light commercial vehicle produced in the UK by Chrysler Europe and later Renault Véhicules Industriels between 1979.

The procurement process began in June 1988, with a contract worth £25 million placed with Reynolds Boughton for 846 RB44 vehicles. The design was accepted in May 1990 after mandated changes costing £940,000, primarily addressing transmission and braking efficiency.

| Feature | Specification |

| Engine Type | Perkins Phaser diesel |

| Power Output | 80 kW (107 hp), likely four-cylinder, though six-cylinder possible |

| Top Speed | 95 km/h (58 mph) against the wind! |

| 0-80 km/h Acceleration Time | 61.5 seconds |

| Noise Levels (Cab) | 74–78 dB(A), depending on terrain |

The RB44’s service history was marked by significant challenges, particularly with its braking system.

Deliveries were suspended in September 1992 after further issues, and by August 1993, 37 out of 57 in-service vehicles deviated left when braking at 35 mph (ca. 56 km/h), prompting a full withdrawal in December 1993. Rectification efforts were substantial, with Reynolds Boughton incurring costs of £250,000 between January 1994 and September 1995, while the MoD faced £1.5 million in total costs, excluding additional storage costs of £1.7 million.

Persistent issues with the RB44 led to its eventual replacement by other vehicles, and it was withdrawn from service by the late nineties.

Replacement Programmes

There have been a handful of replacement programmes, none of which ever concluded.

Operational Utility Vehicle System (OUVS)

The Operational Utility Vehicle System (OUVS) programme started in 2003, Click to read a long form post on it, and it was set to replace…

- 12,000 Land Rovers (TUL/TUM)

- 1,000 Pinzgauer (TUM(HD))

- 850 Reynold Boughton RB44s (Truck Utility Heavy (TUH)) (which were by then out of service)

OUVS attracted great interest from the defence automotive industry, it was going to be a large vehicle order, some sixteen thousand in total, and the procurement method envisaged several shortlisted vehicles taking part in a FRES like ‘Trials of Truth’.

By 2007, the programme was still in progress but could not ignore the reality of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Recognising this, requirements changed to include the ability to be fitted with ECM and appliqué protection.

The initial contenders included a Mercedes-Benz Unimog and G Wagon, a version of the 6×6 Land Rover that was by then in service with the Australian Army, and a version of the Ford F-350 and Ibex vehicles from Ricardo.

All non protected.

By the final down-select, vehicles included the Thales Copperhead, Navistar MXT, an Iveco Panther, Lockheed Martin Adaptive Vehicle Architecture (AVA), Renault Sherpa, and General Dynamics with an Eagle IV Duro IIIP combination

All protected.

After 7 years, in 2010, the Ministry of Defence deferred the OUVS competition, citing the need to reassess industry offerings and integrate lessons from Urgent Operational Requirements, like the Tactical Support Vehicles used in Afghanistan.

Land Rover and Pinzgauer would have to soldier on.

The Multi Role Vehicle — Protected (MRV-P) emerged in mid-2012, and was in many ways a version of OUVS, but one that recognised the need for protection. It, too, did not progress, being effectively cancelled in 2022.

General Support Utility Platform (GSUP)

In 2022, the MoD outlined a new approach.

The Protected Mobility Pipeline Programme was intended to deliver five categories of platforms (as individual projects), plus coherence with legacy platforms:

- Light Tactical Mobility Platform (Light, Medium and Heavy), from quad ATVs to larger UTVs

- General Support Utility Platform and Light Mobility Vehicle

- Light Protected Mobility Platform

- Medium Protected Mobility Platform

- Heavy Protected Mobility Platform

This was an ambitious programme intended to cover everything between a Quad Bike and Boxer. totalling some 16,000 vehicles.

The GSUP requirement was subsequently published later in 2022

The Army is seeking market information as to military light utility platforms as part of an initial scoping of options to replace Land Rover and other similar vehicles as part of the General Support Utility Platform Programme. Companies are invited to provide information on current and developing military utility platforms. Variants of interest include General Support, Ambulance and Fitted for Radio, particularly when these are all included within the same vehicle family. Platforms should be no more than 3.5T and be driven on a Cat B licence (potentially less ambulance variant).

This requirement was clear that the OUVS large type of vehicle, above 3.5 Tonne GVW, was excluded, except for the ambulance variant, although alongside was LMV, that included the heavier variants.

Several contenders emerged, such as the Ford Ranger, Jeep J8, Toyota Land Cruiser 70 Series, INEOS Grenadier Quartermaster, and GM Defense’s Light Utility Vehicle, showcased at events like Defence Vehicle Dynamics (DVD) 2022.

The Light Tactical Mobility Platform (LTMP) was moved out of the Protected Mobility Pipeline and into the DE&S SAM Team (Soldier and *Autonomous Mobility) in 2023.

*Autonomous referring to organic to the force, rather than autonomous vehicles.

Since then, news on LTMP has trickled to a stop.

In 2024, the Heavy category was removed.

By September 2024, the UK MoD issued a Prior Information Notice for the broader ‘Land Mobility Programme (LMP)’.

Land Mobility Programme — The Current State of Play

The Land Mobility Programme (LMP) represents the latest strategic effort by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) to modernise and rationalise the British Army’s fleet of mobility and utility vehicles.

It is aimed at replacing legacy platforms, including those acquired during operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Although it too has been through some change (removing LMP Heavy for example), the programme, with a potential value exceeding £4.8 billion, covers a range of vehicle weights, from light utility platforms up to 7,000 kg to medium platforms in the 20 tonne range

| Vehicle | Estimated Number | Weight Range (kg) |

| LMP Medium | 2,000 | Up to 20,000 |

| LMP Light | 2,500 | Up to 10,000 |

| LMP Utility | 3,000 | Up to 7,000 |

LMP Utility still includes

- Civilian Armoured Vehicles (CAV), discretely protected vehicles

- General Support Utility Platform (GSUP), light 4×4

- Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV), light and mobile tactical platform for very high readiness forces

The MoD’s issued a Request for Information (RFI) for the Light Mobility Vehicle on January 10, 2025, with a submission deadline of February 21, 2025. Tendering is set to begin in November 2025, with selection by October 2026, although this may change in the upcoming Strategic Defence Review (SDR).

Several companies have shown interest and displayed models at defence exhibitions that align with the LMP Utility.

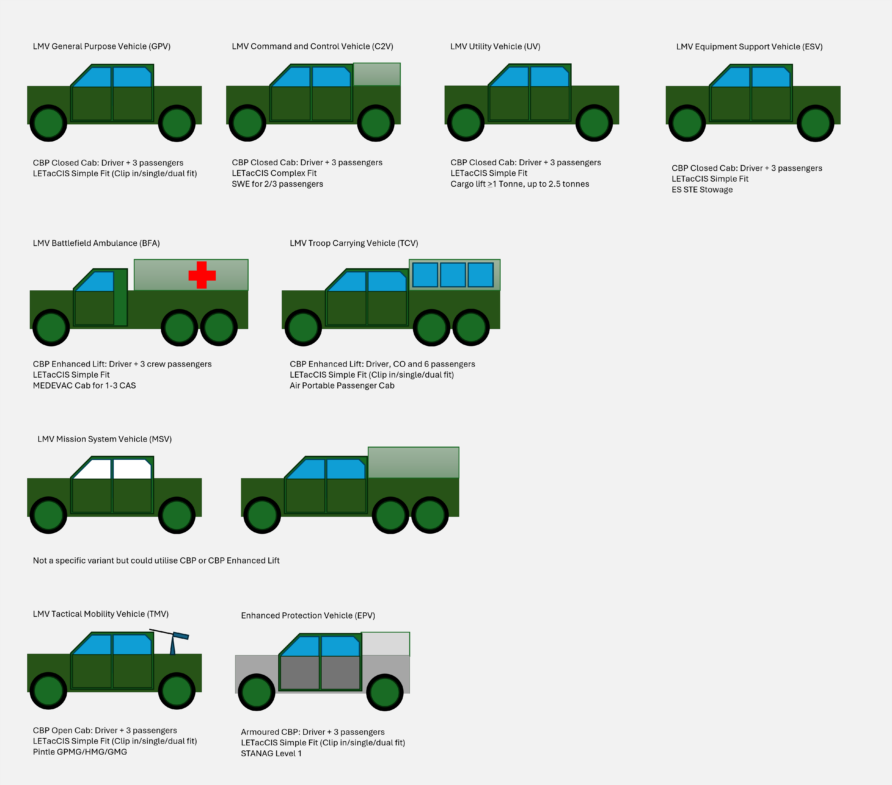

There is now a new requirement that encompasses the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV) and General Support Utility Platform (GSUP), circulated to industry in mid-2024, confusingly called the Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV).

LMV also includes the Tactical Mobility Vehicle (TMV) and Enhanced Protection Vehicle (EPV).

| Variant | Cab | LETacCIS IK Fit | Other |

| General Purpose Vehicle (GPV) | CBP Closed Cab: Driver and three passengers | Simple | |

| Command and Control Vehicle (C2V) | CBP Closed Cab: Driver and three passengers | Complex | SWE for 2 to 3 passengers |

| Utility Vehicle (UV) | CBP Closed Cab: Driver and three passengers | Simple | Cargo >1 Tonne to 2.5 Tonne |

| Equipment Support Vehicle (ESV) | CBP Closed Cab: Driver and three passengers | Simple | ES STE (Equipment Support, Special Tooling and Equipment) stowage |

| Mission Systems Vehicle (MSV) | CBP Closed Cab: Driver and three passengers | Simple | TBD |

| Battlefield Ambulance (BFA) | CBP Enhanced Lift: Driver and three passengers | Simple | MEDEVAC cab for 1 to 3 casualties |

| Troop Carrying Vehicle (TCV) | CBP Enhanced Lift: Driver, Commander, and Six Passengers | Simple | Air portable passenger cab |

| Tactical Mobility Vehicle (TMV) | CBP Closed Cab: Driver and three passengers | Simple | Pintle GPMG/HMG/GMG |

| Enhanced Protection Vehicle (EPV) | Armoured CBP: Driver and three passengers | Simple | STANAG Level 1 |

CBP is a Common Base Platform, with Enhanced Lift indicating a larger than 3.5 tonnes GVM.

This is quite fluid, so will be possibly out of date soon, and I wouldn’t put too much store in the graphics, they are indicative only.

Issues and Considerations

Before looking at requirements and contenders, there are a handful of issues to consider.

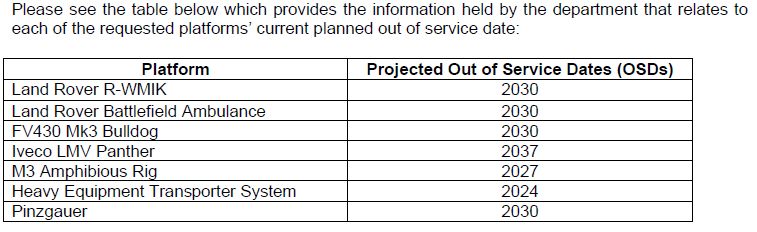

Land Rover and Pinzgauer are on their Last Legs

By 2030, even the youngest Land Rover in the British Army will be three decades old.

An FOI request confirmed the out-of-service date for Land Rover and Pinzguaer.

A recent contract award revealed 65 variants of Land Rover and 31 Pinzgauer variants are in service.

The Conventional Vehicle Systems (CVS) Post Design Services (PDS) Design Authority (DA) contract will commence on 1st September 2022 and is to run for 3 years and 7 months, with an additional 4 +1 option years to extend the period of the service.

This contract applies to all platforms listed below:

Platform: Land Rover Wolf, Variant: 65, Fleet size: 6410

Platform: Pinzgauer, Variant: 31, Fleet size: 873

Platform: Snatch 2b, Variant: 1, Fleet size: 20

Platform: RWMIK, Variant: 1, Fleet size: 187

Platform: Trailer Lightweight, Variant: 1, Fleet size: 7837

The £71m contract was awarded to NP Aerospace in September 2024.

This contract aims to extend the operational life of the British military’s armoured vehicle fleet, including the full range of Land Rover and Pinzgauer models, until the end of the decade (2030).

The deal consolidates previous individual contracts into a single framework, providing spares, post-design services, and maintenance for over 15,000 land vehicles.

Given the state of the current fleet, extending beyond 2030 seems unlikely, Light Mobility Vehicle may well the last chance saloon.

The Modern Vehicle Weight v Payload Issue

Vehicles are getting bigger and heavier.

This weight and size growth has been driven by safety requirements, demand for electrical devices, improved seating, fatter occupants, and other factors.

Military vehicles are not immune to this either.

Because of this, fixed upper weight limits defined by licence classes create a situation where usable payload is squeezed by the base vehicle gaining weight.

For passenger vehicles, this is much less of a problem than for commercial and military vehicles, where payloads are heavier than just the passengers and the weekly shopping.

This issue is made even worse with electrical vehicles, where the powertrain can be much heavier than conventional petrol or diesel engines.

Driving licences are a not insignificant issue for the British Army.

| Licence Category | Maximum Allowable Mass (Tonnes) | Towing Capacity (Tonnes) |

| B | 3.5 | 0.75 |

| BE | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| C1 | 3.5 to 7.5 | 0.75 |

| C1E | 3.5 to 7.5 | Over 0.75 but combined MAM no more than 12 |

| C | >3.5 | 0.75 |

| CE | >3.5 | >.75 |

Since I last looked at this, BE is now automatically added to a B. For the Army, this has been an excellent change.

C is the most popular licence in the UK for commercial vehicles, allowing the licence holder to drive large commercial vehicles like tippers, skip trucks and delivery vehicles.

Another recent beneficial change is that a person can go straight to CE (the old Class 1, essentially, large articulated trucks) from B/BE.

Passenger-carrying vehicles, hazardous cargo and other regulation and licensing issues add to the problem. On top of this, the Army will overlay training and authorisation for specific vehicles (or types of vehicles) within the fleet.

It is tremendously complicated and can have significant cost implications.

Vehicle unladen weight growth meets hard limits imposed by driving licence categories, and this results in lighter vehicles being increasingly unable to carry militarily useful payloads.

The Land Rover to MAN SV 6 Tonne Gap Issue

Both Land Rover and Pinzgauer have limited payloads, needing trailers in numerous instances to make them usable in their intended roles.

Trailers can be extremely useful on long road marches or under specific conditions such as with air despatch or helicopter carriage, but they limit mobility, especially in urban terrain and off-road, and cause unnecessary time delays.

Normally, I am a big fan of trailers, but we also have to recognise their downsides.

The next step up from a Land Rover and trailer or Pinzgauer and trailer is a MAN SV 6 tonne

There is nothing in between.

The 6 tonne payload MAN HX60 is arguably often too much in some cases, and not enough in others.

The LMV Utility Vehicle upper limit for cargo payload is 2.5 tonnes, more or less the same as RB44, or OUVS Small.

One mighty argue that OUVS Large might be a better upper limit, allowing some SV 6 tonne vehicles to be withdrawn, but clearly LMV recognises the need for a larger payload than a tonne, excellent!

OUVS identified a payload gap between a Land Rover and SV 6 Tonne, I think that gap still exists, and using trailers to fill it is limiting

What Roles can be Covered by the White Fleet (in Green)

The MoD outsources management of the non-operational fleet of cars, vans, trucks and specialist vehicles to Babcock under the Phoenix II contract.

The Military Provost and Guard Service use Ford Ranger XL pickup trucks.

We already have a mature contract and experience with utility vehicles provisioned through lease partners.

We also have more defence oriented vehicles provisioned through an availability contract, the Iveco Trakker variants used in the C Vehicle contract for example (there are others as well)

If they are mostly used by the QM as a means of moving rations (range stew and cofftea) on a range day or escorting a vehicle packet, do we really need a 24V DC GVA Compliant ‘platform’?

Or

Would a minimally modified off the shelf civilian 4×4 van or pickup truck do the job just fine?

Shifting as many roles into a ‘White Fleet’ type arrangement allows the fleet to be turned over much quicker, more easily accommodate regulatory and technical changes, and avoids the need for worrying about support over twenty or thirty years.

The contract could be let in multiple packages to improve resilience and spread economic benefit across the UK.

If the contract were kept at 3 to 5 years, it could be adjusted to suit a changing force, avoiding having to release relatively new vehicles to disposal agencies.

It would also allow many existing vehicles to be quickly replaced, buying time to avoid making rushed (last chicken in the shop) decisions.

These existing vehicles do actually have decent market value, as the military Land Rover enthusiast market is extremely vibrant. On the reverse of this argument, the iron law of supply and demand applies, dumping several thousand Defenders onto the market will depress market value.

The contracting arrangements would have to account for different treatment profiles (they might get harsher treatment than the existing white fleet), and possibly need some off-road recovery provision.

The more demanding roles could then be subject to a more traditional approach.

The only problem with this approach is internal barriers, recognising a wider use of lease vehicles would mean additional compliance processes, separate noise and vibration testing, rollover protection, and a wide range of human factors compliance.

Is this a case of MoD internal processes impinging on lower cost and pragmatic solutions?

Moving as many roles as possible into a leased fleet (revenue instead of capital) could provide space and time to compete the more demanding roles, allow a more rapid replacement of the bulk of the general utility fleet, and avoids long-term support concerns for what is, a low-value vehicle. This assumes MoD processes would allow it.

What About Them Drones

The conflict in Ukraine has amply demonstrated the risk of FPV’s, drone dropped munitions and drone supported artillery.

We cannot ignore this.

The most obvious result of this should be that an increasing number of roles currently covered by the utility fleet are moved into the protected mobility fleet, especially if this is developed and expanded.

There are obvious cost implications, but a small army like the British Army must value its increasingly scarce personnel.

Recognising financial reality also means that not every role can be covered by a Foxhound Mk2, Dingo, Bushmaster, Supacat HMT ACC, or Nurol Makina.

Which leads to the second most obvious result, any vehicles in this category should be fitted with mesh screen attachment points and other appliqué protection.

The evolution of low-cost armed drones means that we should retest some assumptions about where unprotected vehicles can be used, potentially moving more of them into the LPM Medium Category

Land Industrial Strategy, Net Zero, and Dependency Risk

The UK aerospace industry has a turnover of £35billion, the shipping industry; £3billion, both lobby for the RAF and RN, respectively.

The hugely innovative UK automotive industry has a turnover more than double that combined.

That said, no volume manufacturer of this class of vehicles exists in the UK.

There are a few minor exceptions that I will cover in subsequent parts of this series, but in the round, UK industry will be at the component level, and for integration and assembly.

Although I only scratched the surface in this post on the UK defence vehicle sector, it is more comprehensive than one might imagine.

Recent events have shown how political change can be rapid, and effects, sometimes unpredictable.

Avoiding this risk can be helped considerably by spreading exposure to any one nation or supplier, avoiding eggs and baskets.

With MAN trucks, CR3 and Boxer, the British Army is heavily exposed to the German defence sector. Horstmann and WFEL have also recently been purchased by Renk and KMW (now KNDS) respectively, and of course, RBSL is majority owned by Rheinmetall and I would not be surprised if the BAE element was eventually divested, leaving Rheinmetall.

We should think carefully about increasing this dependency.

The integrated operating concept talks about being markedly less dependent on fossil fuels, and the MoD has invested considerable sums on various projects and programmes for electrical and hybrid vehicle power systems.

Of course, future technology insertion programmes could be used as maturity increases, but again, we should question whether many roles would lend themselves well to electrification or hybrid approaches.

The Light Mobility Vehicle programme has to recognise the limits of UK industry participation, but neither should it ignore the risks inherent with overdependence, or the benefits of maximising UK industrial participation and alignment with wider government objectives on climate.

The Siren Song of Commonality

Many years ago, in response to the proliferation of vehicles and equipment for (understandable reasons) during the Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns, I coined a phrase to describe how we should come out the other side.

‘Ruthless Commonality’

This was intended to illustrate the benefits of standardisation, using a fewer unique parts or components as possible, re-using at every opportunity, and eliminating equipment that does more or less the same job as another in service.

There is a point, though, where the entirely logical and laudable objective of reducing cost through commonality, works against us.

I think this vehicle programme might be one of them.

Demanding requirements like Chinook internal carriage for the Tactical Mobility Vehicle (TMV) variant being met with a common vehicle that is also used for a command post or for moving a few stores, can create suboptimal choices.

For example, 16AAB might well be ideally served by the Flyer 72, but no one is going to use that specialised vehicle for a GS role.

The GM Defense ISV could equally have great utility as a troop carrying vehicle, but no one is likely to recommend the GM Silverado as the ideal solution for Battlefield Ambulance.

Trying to a shoehorn a single vehicle platform into every role, minimises choice to a few solutions and suppliers, and I think actually increases risk overall.

Look back at older programmes, and they all appear to have recognised this.

Instead of seeking vehicle platform commonality, would looking at the three main configurations (3.5 tonne, 7 tonnes, and WMIK/Protected) separately provide a much better outcome, each optimised for the role?

Summary and Look Forward

Because of a range of both internal and external factors, the British Army is getting very close to shopping on Christmas Eve.

The last time it seriously looked at Land Rover and Pinzgauer replacement was in 2003, and the current programme has been running since 2022.

None of this is easy, but the continual deferral of replacement will reduce realistic choice, sadly.

We can endlessly opine about this, but we have to look forward.

The next few years will be crucial.

The next post in the series will look at requirements.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I have a fondness for the ACMAT VLRA family. According to t'internet there are 70 factory options.

Does the Heavy Equipment Transporter System really have out of service date 2024? Are the transporters all gone, or was that a typo?

They have recently been extended with a new contract Paul