I am not sighted to the specific requirements, but a few thoughts on matters relating to the command and control and battlefield ambulance Light Mobile Vehicle (LMV) variants.

Command and Control — Alternatives to the 9×9

Communications technology is rapidly changing, the Land Environment (LE) Tactical CIS (Tac CIS) is an expansive British Army programme that covers communication and information systems.

Within this are four big projects;

- TRINITY: Battle space broadband, a Wide Area Network (WAN) capability providing connectivity to higher HO’s and high bandwidth users DSA.

- Dismounted Situational Awareness: Meshed radio network with collaborative real-time planning for dismounted infantry

- BCIP 5.7: An update to the in-service Bowman system providing data and voice services for tactical users. Optimised for war fighting, but of use across the spectrum of operations.

- MORPHEUS: The core of the next generation tactical C4l capability, underpinned by both open architectures and the enabling processes to allow evolutionary capability delivery

BOWMAN withdrawal and MORPHEUS introduction will be on a time-based crossing line that intersects with LMV, another challenge for the LMV programme to manage, even though the delays announced recently will elongate that window.

The LMV command and control variant will be for subunits, small radio rebroadcast, and similar roles, not the larger HQ’s.

To be usable in the role, a Land Rover Fitted For Radio (FFR) needs personnel to pack and unpack a trailer, erect a 9×9 tent, move furniture, and set up a generator.

They have to do this in reverse every time they move.

When I wrote about the Command Post Environment in 2022, I touched on the matter of ergonomics and time spent setting up and moving, using a comment from Twitter to illustrate the point.

Wellington’s army, pulling a trailer with a Landy across Salisbury Plain and wasting a copious amount of my and my det’s time building tents, moving furniture in, using map boards and pins, remoting UCDs, UDTs and ancills and digging a very misnamed LFG?

Why?

Whilst it is hoped that whatever succeeds BOWMAN will be smaller, the inexorable rise of connected devices and demand for more connectivity may offset that.

If it is based on a >3.5 tonne vehicle, a modern Command and Control Vehicle (C2V) is unlikely to substantially change this. It will still need a trailer and a canvas shelter, sucking up time and resources when agility is critical.

There are alternative options.

Integrated Van

1 DIV actually experimented with a van-based command post a few years ago.

Whilst I am not necessarily saying we should use a white van, for obvious reasons, a van style vehicle provides a better base vehicle for integrating a command and control space than a pickup truck.

Something like the image below with an integral generator/battery so it does not need the vehicle engine to be running.

Being generous, a 9×9 tent has a volume of approximately 15m3.

A high roof long wheelbase Ford Transit AWD with three seats has a load volume of 15m3.

Is a 4WD drive van likely to be as agile as a pickup truck style vehicle, probably not, but does it need to?

Additional briefing space can be provided by roll out or fold out awning type systems. They take a few minutes to deploy, plus some time to add wall panels

Watch the video for just how quick, and compare that to a 9×9.

The design would need some modification to make it suitable for defence uses, but the general concept has merit.

The main problem with using an AWD van is the usable payload, like pickup trucks. Could the electrical and electronic systems, furniture, and internal fit-out come in at under a tonne?

That would be the challenge.

Trailer

Accepting that LMV can tow a trailer, a middle ground might still make use of trailers, but integrated shelter trailers, like this from Weatherhaven

The fully insulated TRECC-T has a deployed volume of 24m3 and weighs 907 kg.

With two people, it can be deployed and ready for use in less than 5 minutes. It can also be fitted with roof-mounted solar panels. Larger versions are also available.

The Estonian company Rolling Unit manufactures an interesting trailer mounted expanding shelter, larger than the TRECC-T.

I’m sure there are many more from a range of manufacturers.

The Command and Control Variant of LMV then becomes a vehicle and trailer combination, not just a vehicle.

Removing any need for the vehicle to have working space would allow the load space to be used entirely for equipment racks, cam nets, soldier equipment, power systems and removable masts

The latter would be on a roof rack of some kind, instead of awkwardly poking out the back of a trailer.

Something like this, from Pickup Systems in Burnley.

Although the communications technology would be different for the British Army, the EE Emergency Response vehicles as per the image below could also be a good template to follow.

A basic facility for the driver and crew to communicate whilst on the move would not be difficult to implement, but fundamentally, the crew and operating space would be in a trailer (or other space of opportunity).

We can do this now to some extent, but the emitters would be remote from the operators, probably not a bad thing in the round.

Completely Disaggregated

Another way of looking at this is to eliminate the requirement entirely, making everything demountable and able to exploit spaces of opportunity.

Arguably a bit extreme, but it would eliminate a variant.

Large Shelter, Larger Vehicle

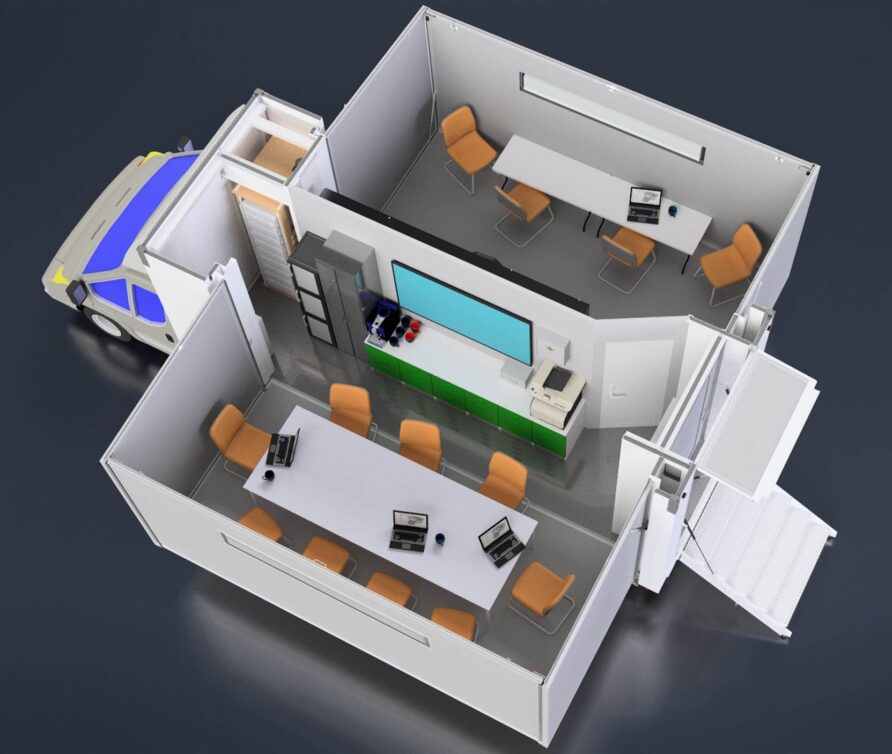

Indirectly related to LMV, at a larger scale, the British Army recognises the need for agile command and control spaces, bringing into service the LELANTOS (AGILE C2) expanding container equipment.

Why not at a smaller scale?

The issue, again, is weight against a limited payload to keep the vehicle under 3.5 tonnes GVM and drivable on a B licence.

This leads to a conclusion that any larger shelter for command and control would likely require the higher GVM version of LMV, up to 7 tonnes.

Supersizing would provide a much more usable space and enough payload for all the electronics and power equipment, although it would no longer be drivable on a B.

As combat teams become more distributed and mobile, monitoring different nets because a challenge that requires space and people.

A simple fixed shelter could be used, possibly disguised as a more common logistics vehicle.

Or a more complex folding type.

Depending on need.

Should we copy the Defender FFR and 9×9 concept over to LMV, or do the alternative options provide more utility?

Ambulance

This is quite a demanding role given requirements for a high roof and larger volume, medical gas provision, and higher levels of system integration and power.

Boxer will be a step change, and hopefully, an ambulance version of Ajax will also enter service.

Which leaves the non-protected ambulance variants with Light Mobility Vehicle (LMV). The LMV requirement is for the Battlefield Ambulance to be an ‘Enhanced Lift’ variant, indicating a larger payload vehicle, with a MEDEVAC cabin for 1 to 3 casualties.

BS EN 1789:2020+A1:2023

Medical vehicles and their equipment. Road ambulances

This document specifies requirements for the design, testing, performance and equipping of road ambulances used for the transport, monitoring, treatment and care of patients. It contains requirements for the patient’s compartment in terms of the working environment, ergonomic design and the safety of the crew and patients.

Would a Sub 3.5 Tonne Ambulance be Useful?

The East Midlands NHS Ambulance Trust has a 4×4 Volkswagen Amarok based ambulance for accessing harder to reach areas.

Tamlans in Finland, who did the integration and design work, have a defence variant of the same model.

The interior is designed for a single patient.

Whilst it has reasonable off-road performance, they are fast on the road.

There are numerous other integrators that provide ambulance conversions for vehicles including the Ford Ranger, Toyota Hilux, Toyota Landcruiser, and Mitsubishi L200.

Low Roof

High Roof

BSE in France, Carryboy in Thailand, EOS in Turkey, Paramed in the UAE, and IAG in Bulgaria. And that is before we even look at those in the UK such as O&H, AEV, Wilker Group, Cartwright Conversions, Meditransport, and E1.

Perhaps a little out of scope for the LMV programme is high-capacity casualty transport, especially in the context of high intensity operations. Although legally not permissible, using a 3.5 tonne trailer (similar to a lightweight box trailer or car transporter trailer) would allow a lightweight ambulance to move circa 15 stretchers at road speeds.

Accepting the reduction in patient capacity, would a sub 3.5 tonne GVM ambulance be useful?

Protected or Not?

This is a Bogdan 2251 Ambulance in service with Ukraine.

And so is this

Given recent trends in UAS/FPV, and the general political/legal climate, should we retest assumptions about non-protected ambulances?

Boxer and whatever comes through the protected mobility platform programme will provide protected ambulances, but if we accept that in many situations, the ambulance exchange point will be increasingly further back.

The round trip cycle time for those protected ambulances will increase, slowing down the whole process.

There are options to add lower levels of protection to lightweight wheeled vehicles, and ambulances are no different.

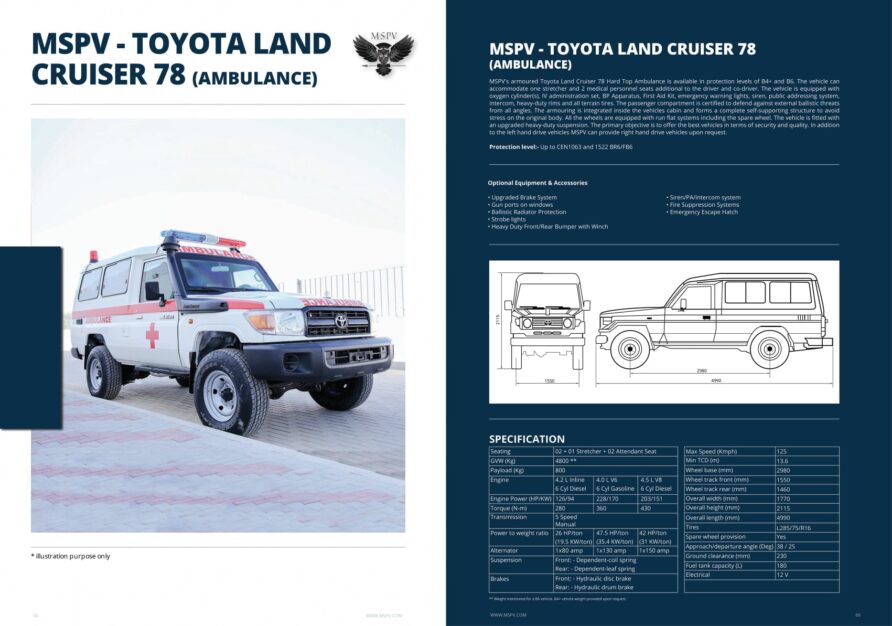

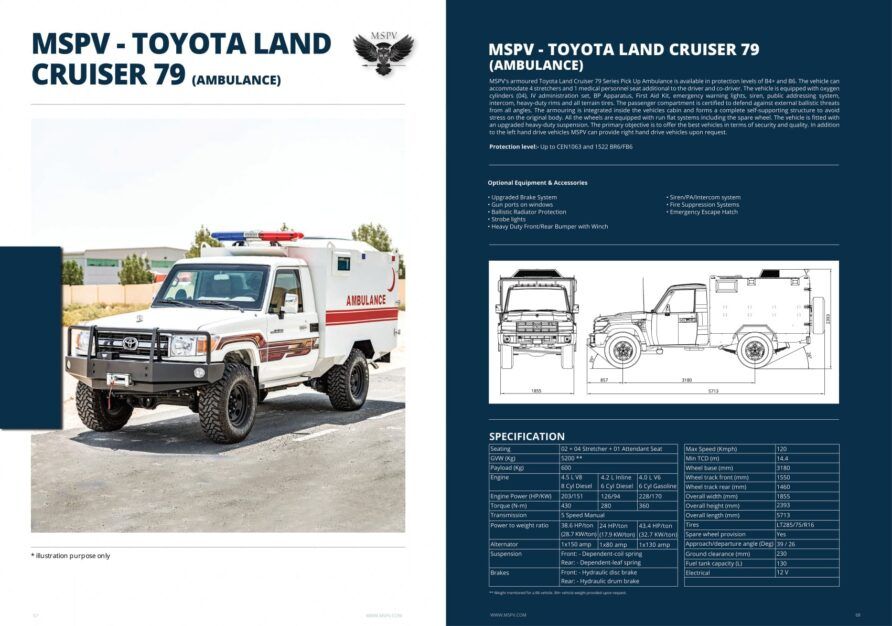

Protected ambulances based on the Toyota Land Cruiser are quite popular in the Middle East, this one with a Gross Vehicle Mass of 4.8 tonnes.

And this one, with slightly better protection levels, a larger box body, and higher GVM.

Others are available from Mahindra Emirates and Alpine Armouring.

Moving up in size, these protected Unimog ambulances were provided to Ukraine by O&H in Goole.

With an internal fit that looks quite similar to the Land Rover Battlefield Ambulance.

Or maybe, move most of the battlefield ambulance role to a protected vehicle?

How Much Mobility is Enough Mobility?

In future high intensity operations, alongside an increasing willingness to target medical facilities, military hospitals may need to be further back from the fighting than current assumptions.

This will elongate evacuation routes between echelons and perhaps place a premium on transfer speed from the forward exchange points.

Which raises a question about mobility and patient space.

Is road speed more important than wading depth or traction in the mud?

Is the ability to shift a dozen patients with a single driver and a couple of medics in a single vehicle more significant than moving the same dozen patients with four vehicles and triple the personnel?

This could drive a hi-lo mix of vehicles.

Out of scope for LMV, but a large patient transfer ambulance would provide road speed and capacity.

This could be achieved with a 20 ft (ca. 6 m) protected ISO container-based system on a conventional and in-service truck, like this from Airbus and Dhretainer, weighing 13.5 tonnes.

The Bundeswehr took delivery of thirteen of these, under a 39 million Euro contract, about 3 million each. They can transport eight patients with three medical personnel.

At the other end of the protection scale, another option would be to convert a civilian coach, Norway donated five of these to Ukraine in 2022.

Although not common, these are in service with many organisations.

I have included both those options for completeness, but a more relevant capability is that which would enable the British Army to convert smaller civilian vehicles and military vehicles for patient transport.

First Line Technology in the USA manufactures a tool-less modular system for conversion of vans, trucks, and buses to high-volume patient transfer vehicles.

The AmbuBus Quick Response Transport (QRT) frame system allows a standard van to carry three stretchers on one or both sides.

Using a long wheelbase van would also allow two bays lengthwise, for a total of twelve patients.

The larger Ambubus is designed for buses, coaches, and trucks.

On its own, this is rudimentary, and would need to be joined by other medical equipment and supplies, but if numbers are the game, is it difficult to argue against this type of solution?

Where there is a need for higher levels of mobility, could a hi-lo approach work.

The Battlefield Ambulance being covered by something like a 4×4 van, and high mobility requirement (at a lower quantity), covered by a UTV type design?

There are a few of these combinations in service in the UK.

Some even use a hooklift container for double bonus points!

Also out of scope for LMV, but one for discussion.

Should we copy the existing Battlefield Ambulance concept over to LMV, or do alternative options provide more utility?

Summary and Look Forward

Has the Light Mobile Vehicle (LMV) requirements been carbon copied over from the Land Rover variants for Command and Control, and the Battlefield Ambulance?

Is this a good time to re-examine those requirements and re-test assumptions about how these vital functions are delivered?

The next in this series will look at fuels, and the logistics requirements.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One limitation/consideration on the whole LMV programme is where the drivetrains of the civilian fleet is going to end up. A series hybrid would allow them to operate outside an electricity grid but provide ample power without need for a separate generator, but is battery technology enough to make it work within the weight limit?. Certainly any power generation ought to be integrated, but is there room/mass or even need for a separate generator on a 3.5t vehicle?

I like the idea of a van for command vehicles, but at the same time I wouldn't think that a unique vehicle for a high value asset is a particularly good idea. A mix of command vans and cargo vans? Maybe even section transport vans? Though those might need additional licenses to fit more than just the soldiers.

Can an AWD van maintain sufficient off-road performance?

There's no real reason for a 3.5T ambulance, as the existing Land Rover based vehicles are 4.5T and your standard NHS ambulance is a 4.5T. As these are driven by persons with specialist training, the licence isn't an issue.

On the command vehicles, the 3.5T AWD Vans offered by the major suppliers are mainly designed to cope with muddy building sites than proper off roading. That's probably not good enough for military needs. TORSUS in the Czech republic do a more serious off road conversion for 3.5T MAN Trucks as the Terrastorm which might meet the off road requirement. The coach version seats 7+1, so would make a plausible section transport.

Much of LMV will be 3500Kgs, much of it will be over 3500kgs, physics and experience tells us that.