The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has rapidly accelerated the development and deployment of unmanned aerial systems (UAS), particularly first-person view (FPV) drones, which have become pivotal weapons for both sides.

Counter drone nets have a role to play in defeating the threat.

Threats and Defeat Mechanisms

But, there is no single drone threat to counter.

Threats

They can range from small FPV type drones weighing a few kilograms, even with the weight of the latest fibre optic guidance systems.

To loitering munitions like the Lancet, weighing 12 kg, with a 3 kg warhead.

And large loitering munitions like the infamous Shahed that weighs 200 kg, with 50 of that being a warhead, are in the mix.

Defeat Mechanisms

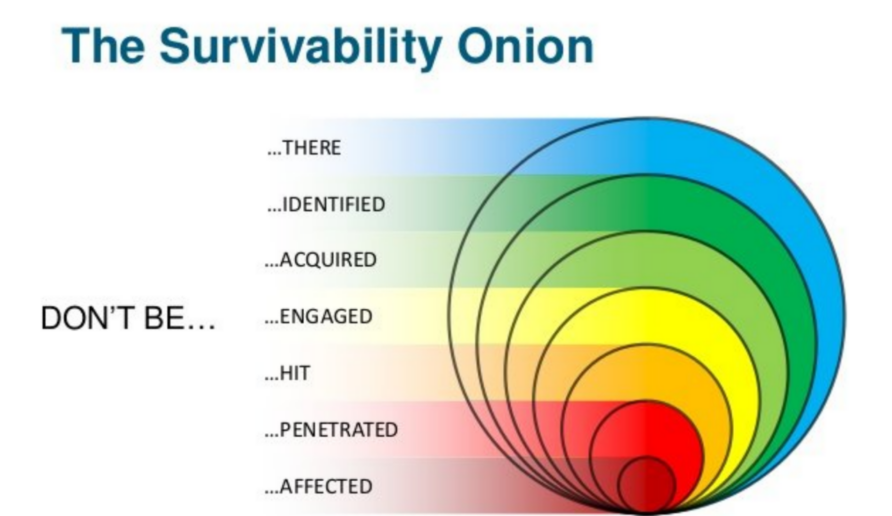

It is always worth wheeling out the survivability onion to frame a discussion.

Effective camouflage and fieldcraft play a massive part in defeating drones of all types and sizes. As do active countermeasures like guns, missiles, and ECM, and not forgetting activities to kill the archer not the arrows.

No doubt we will also see RWS and Active Protection systems evolve to counter drones as well.

So where does this leave the nets?

In Ukraine, beyond the various active weapon and electronic countermeasures, rudimentary but effective countermeasures that utilise physical barriers like nets and mesh screens have been widely fielded to protect firing positions and battle trenches.

The basic premise behind using nets and cages against drones is to physically entrap or disrupt them, or force them to explode at stand-off distances.

There are numerous videos and images from Ukraine of drones that have been defeated by nets and mesh screens.

From the lightweight FPV.

To the larger Lancet.

We know they work, although you would be better defeating drones at the outer layers of the onion.

Obviously.

Counter UAS nets are not a panacea, and should be considered one (cheap) component of a wider systems approach.

There will be some obvious crossover, but for further discussion, I am going to consider three use cases where counter drone meshes might be worth further investment.

Options for Dismounted Infantry

Patrolling

Lightweight nets need minimal fixings and almost no tensioning, the defeat mechanism is to snare exposed rotor blades and prevent forward passage of the drone body.

In numerous instances, no fixings at all will be required. The net can simply be wrapped or hooked on branches, doors/windows or other convenient fixtures.

Where some additional fixings are required, cable ties are cheap, quick, and easy, and add no metal content. They are available in standard lengths up to 1.5m and in various colours, and can be used to join multiple nets as well as fixing.

As long as there is some fixture to affix to, lightweight mesh nets can be secured and tensioned with simple knots and cordage or paracord. The advantage of this is no metal content and absolute simplicity. Nite-Ize Cam Jams, although not super cheap, are very fast and require no skill to use.

In an urban or mixed environment, securing doors, windows, and other apertures from drone penetration will need to be completed quickly.

To reduce weight, a lightweight mesh would be preferable, something like a 50 mm mesh pigeon control net.

A 3m × 2m panel (with a selvedge edging) would only weigh 150g.

If there was a hammer available in the team, cable clips would make a secure enough fixing.

Screw in vine eyes are commodity items and could be included in the kit. They are not suitable for masonry or concrete surfaces (without a plug), but don’t require any tools.

Other designs can be used if power tools, like a simple battery operated drill, are available across the wider team

With hand or power tools, these can be quickly fixed to various surface and the mesh attached to them, either directly, or with cordage and cable ties.

Nails and screws means that a hammer and screwdriver must be carried, less of a problem for vehicle borne personnel or where engineer support is available, but for dismounted infantry, especially in an urban environment, every kilogram matters.

Lightweight plastic hooks could be used with construction adhesives.

Modern construction adhesives might be strong enough to support the weight of a lightweight mesh/wall hook, can be used on a wide variety of surfaces, and cure in minutes.

They are also readily available in small tubes, 75ml to 150 ml, for example.

These are lightweight fixtures for lightweight mesh that is not tensioned.

The only load it bears is itself, and the defeat mechanism is simply to ensnare exposed FPV/UAS rotors.

Half a dozen mesh panels, together with a pack of hooks, nails, clips, cable ties, paracord, a couple of tubes of construction adhesive, and even a small hammer could be supplied in a stuff sack. You then have a flexible kit for use by dismounted infantry in an urban setting, able to stairways and door openings.

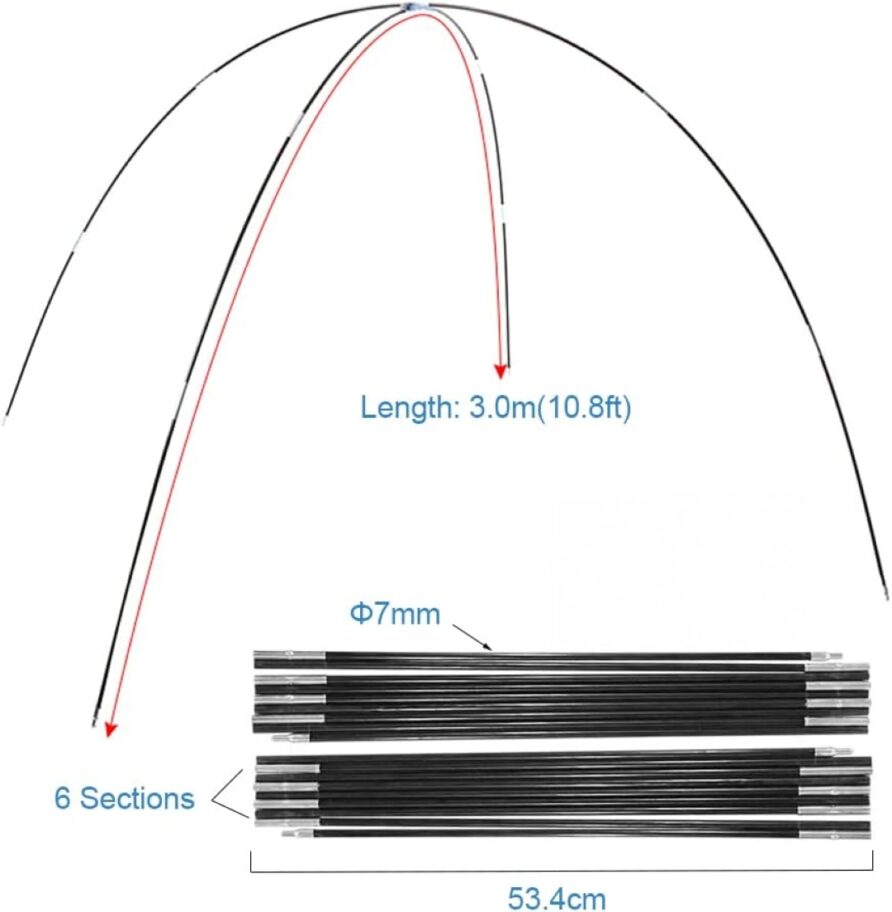

Being out in the open, might also need the infantry to carry some lightweight poles to secure the mesh. The lightest frame, for lightweight nets, is likely to be collapsible fibreglass tent poles, tensioned with an internal shock cord.

Everyone is familiar with these, and they are easy to carry. With simple cordage and ground pegs, they could easily be used to quickly create a frame over a temporary stop location.

These small domes might be less useful, though, the stand-off distance they would create is minimal.

Battle Trench and Fighting Positions

As discussed in the post on battle trenches, concealment should be a more significant feature of our design and build process.

But where there is a more time to dig a defensive position, counter UAS should form part of the design.

Let’s talk about cricket, this is a British defence blog after all.

For about the same cost as the cheapest 81 mm mortar bomb, we could obtain one of these for the 81 mm mortar team.

Nothing more than a pop-up batting net.

Although this would limit arcs of fire, it could be quickly repositioned as needed.

This exact approach could also be employed over battle trenches if applicable, these are all lightweight options that would only be useful against lightweight drones.

Options for Vehicles at the Halt

Vehicles might have integral counter drone mesh, and that is slightly out of scope for this post, but when at the halt, a temporary outer layer might also provide additional protection at much greater stand-off distances.

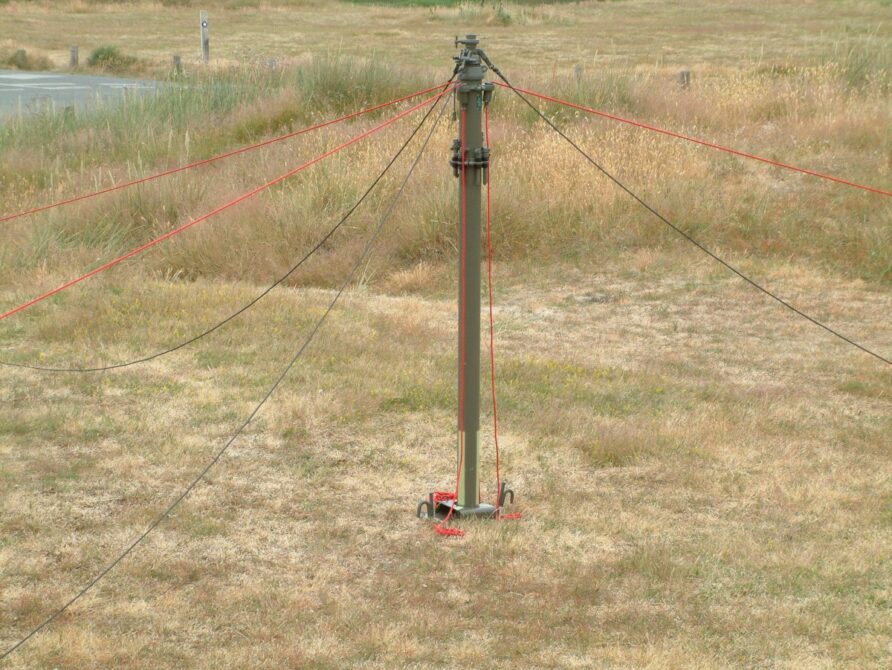

The British company, Rolatube, makes a range of lightweight and compact masts and tripods, in limited service with the British Armed Forces.

The clever thing about Rolatube is that the lightweight mast comes on a reel, no, you haven’t heard that wrong.

Watch how it works in the video below.

The system is provided in a kit form, with components matching the specific requirement.

For vehicle applications, one could imagine a RolaCage affixed to each corner.

At the halt, the vehicle crew could attach suitable nets and guy lines to the top fixture, and deploy the four corner masts to elevate the whole assembly.

Then, drive pickets and tension.

This could be done in short order and combined with multispectral camouflage.

If that vehicle had an active protection system, something like this would reduce its effectiveness, so careful thinking needed.

Options for Vehicle and Artillery Hides

Vehicle hides would provide a greater level of protection than the ‘vehicle at the halt’ system described above.

They could be used in a rural or urban setting.

Because of their semi-permanent nature, and time available to build, there are options beyond lightweight mesh nests that can be used to counter the larger Lancet type drones

There are two defeat mechanisms, the first is still ensnaring exposed rotors, but where rotors are less exposed or the drone larger, a more sturdy defeat mechanism is required to physically destroy or disrupt it.

This requirement can be met with either a rigid mesh panel, or a highly tensioned flexible mesh that resists deformation.

Rigid Mesh

The image below shows the use of anti-climb steel fencing panels in Ukraine.

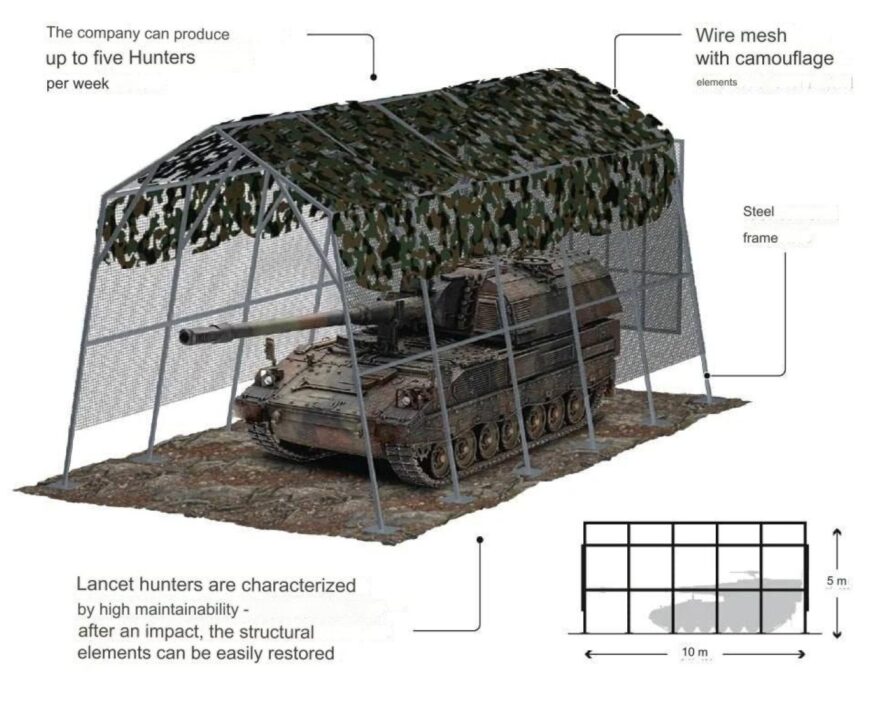

This is an example of a Russian position with a rigid steel frame and mesh

There is no need for any tensioning systems, and installation, I imagine, would have been quick.

At first, these rigid panels were improvised.

And they have proven to be effective.

But as one might expect, Ukraine has started to iterate designs and manufacture complete solutions for vehicles and artillery.

Metinvest produces the Lancet Catcher to protect vehicles from large loitering munitions.

As described by Metinvest

The weight of one mobile shelter, which is ten metres long, five metres wide and five metres high, is about one tonne. The shelter consists of a steel frame and a chain-link mesh with camouflage elements stretched over it. Metinvest can produce up to five lancet catchers per week.

Note the use of chain-link fence, not fabric mesh or netting.

The UK is not short of manufacturers of this type of anti climb fencing panel.

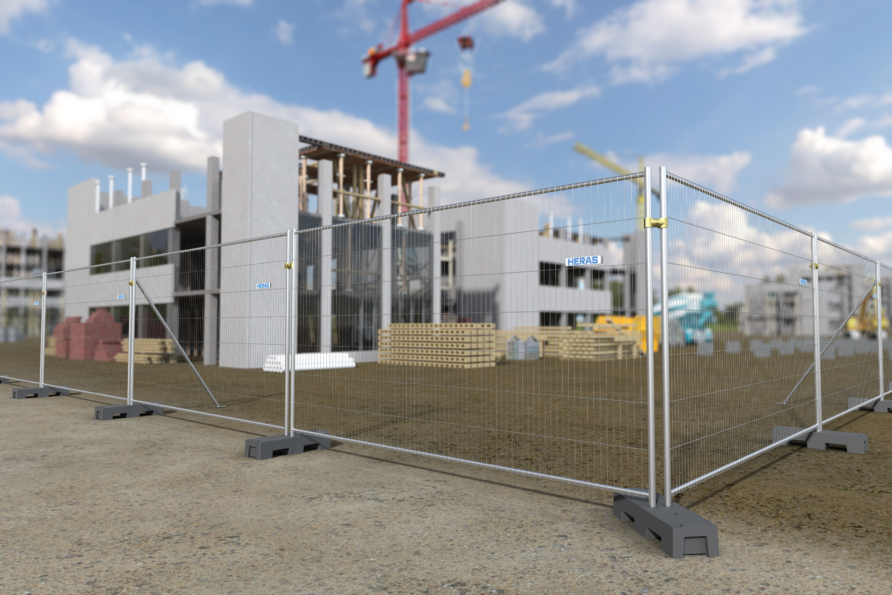

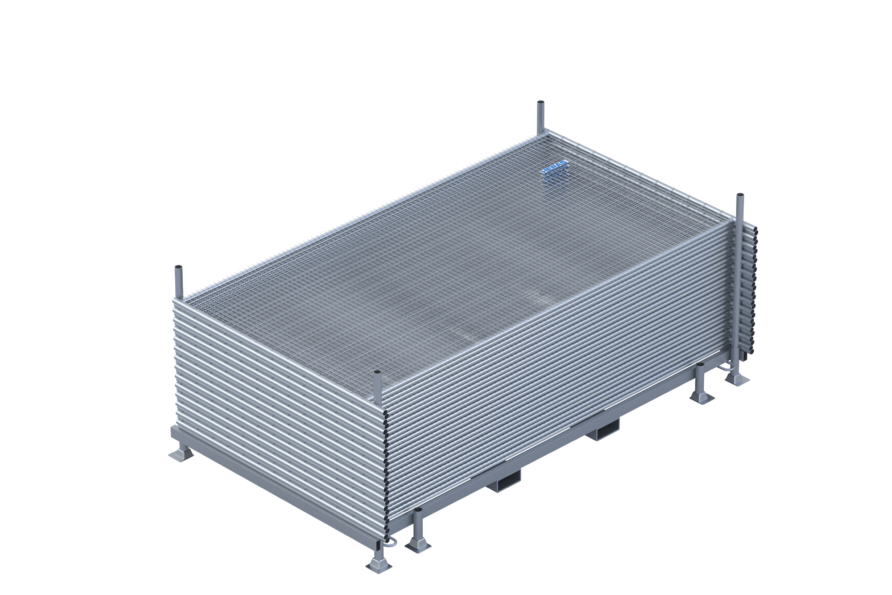

It would be easy enough to contract the manufacture of these, but if an off the shelf solution is needed, Heras security fencing fits the bill quite well.

Rather than separate fence panels and a frame, Heras style security fencing is a complete solution.

Different panel sizes are available, but the standard is 2.025 m high by 3.45 m wide.

Panels can be clipped together and stabilised with metal feet or ballast blocks.

The accessory range also includes castor wheels

Alternatively, a door kit is available.

Stabilising struts and soil pins are used to improve strength and stability.

The same panels could be used to provide overhead cover, or simply used as anchor points for netting.

A stillage can be used to transport multiple panels.

Sliding panels can be created by using steel wire rope and flexible mesh.

Flexible Mesh

Back to cricket.

For less than the cost of a single round of 155 mm ammunition, we could buy a couple of these for our Archer 155 mm SPH.

Maybe even splash out for a door.

There are plenty of other solutions, retractable car ports and spray booths, or we could even just use surplus tentage frames and instead of canvas, fix mesh or netting.

But most of these would only support relatively lightweight, flexible mesh.

Galvanised steel netting may be a more suitable alternative to rigid fencing panels.

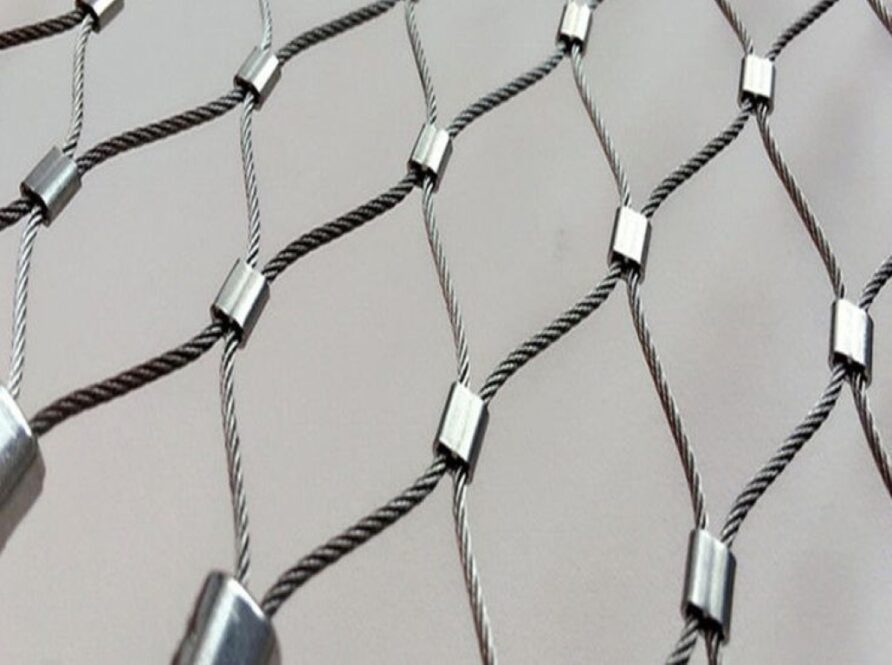

Another mesh type in increasing use, especially for anti fall applications, is the ferrule type

These are strong.

AmSafe Bridport Tarian is another strong and flexible mesh option,

Frame systems like Unistrut or Kee Klamp described in the previous post(s) could be used to support these heavier duty mesh types.

These are cheap and simple solutions that are readily available.

GRP poles are available in the same diameters as those used with the Kee Klamp style fittings.

They are fixed length, but easily cut and compatible with the full range of fittings, such that almost any dimension frame could be quickly built.

Guying Systems and Double Layers

For medium weight nets and even rigid panels, sturdier tensioning systems may be required to build in strength.

Gripple markets a Garden Trellis Kit that comprises four Gripple X10 tensioners, four screw in vine eyes, and 50m of nylon trellis wire. Ready-made for fixing and tensioning a single mesh panel (top and bottom), and with minimal metal content, and less than fifteen quid.

The fencing and industrial sectors also have products for heavier duty fixing and nets.

Gripple, again, the Dynamic fastener can be used with 4 mm or 6 mm wire rope.

For ground anchors, another British company, Spirafix

They have a 10 mm hex head so can be driven manually, or with power tools and excavator attachments (at the larger sizes)

Once driven to depth, tethering brackets and eye bolts are fitted.

Available in a range of lengths and diameters, these are industrial class products.

Gripple and Vulcan anchors have an interesting set of products that use a pivoting anchor plate.

When driven (using manual methods or machines), the anchor tendon is drawn back using a specialist tool (Gripple JackJaw) to provide a firm fixing.

The video below shows how they work.

Rod, fibre, and wire rope tendons provide different load ratings.

Irregular shapes, and where a stronger barrier is required, could be secured using steel wire rope and connectors, as shown below, or with cable ties.

Taken together, these can be used to create a highly tensioned outer layer that can resist heavier drones and loitering munitions like the Lancet.

As drones evolve, it seems certain they will do so to defeat counter drone nets.

Precursor charges may be used, tandem attacks, and other means of destroying physical barriers.

A combination of tube and clamp systems, steel wire rope fixings, and rigid panels, could be used to create multiple layers to protect high-value equipment.

Options for Large Areas and Infrastructure Protection

There are hundreds of types of lightweight mesh readily available in a bewildering array of sizes, mesh sizes, and materials.

Pop over to Huck for a look at Sports Netting, Safety Nets, Bird Nets, and Industrial Nets

Some of the lightest nets are those used for bird control, a 100 mm x 100 mm mesh heron net is approximately 15g per square metre, ideal for dismounted infantry use. Decrease the mesh size to 50 mm, widely used for pigeon nets, the weight rises to 20g per square metre, but still light.

They can be provided as plain nets on a roll, cut sheets, or with securing fixtures, cord edges, and eyelets built in.

Nets are available in long lengths and roll sizes, suitable for infrastructure protection or large areas and urban areas.

These all make use of lightweight mesh, but because of their nature, can be tensioned, and stood off from the infrastructure a considerable distance.

Multiple layers can also be employed, but the bird protection and scaffold industry is likely to have the richest vein of potential solutions to mine.

Deployed Infrastructure and Larger Areas

For larger mesh screens and nets, scaffold poles and quick setting Postcrete could be used, its initial cure is only ten minutes and this would be ‘strong enough’. Simply driving posts into the ground is also a viable method for larger installations, although this would require mechanical assistance or some jointing

If available, timber can be used as an improvised support for lightweight mesh, as shown below, used for large areas and supply routes.

Or more conventional telescoping masts.

We are not short of telescopic masts, they could be easily repurposed, or, simply buy a load of new ones from Clark Masts.

The safety need for non-conducting poles for cleaning, access, inspection, and installation has driven the widespread availability of composite telescoping poles.

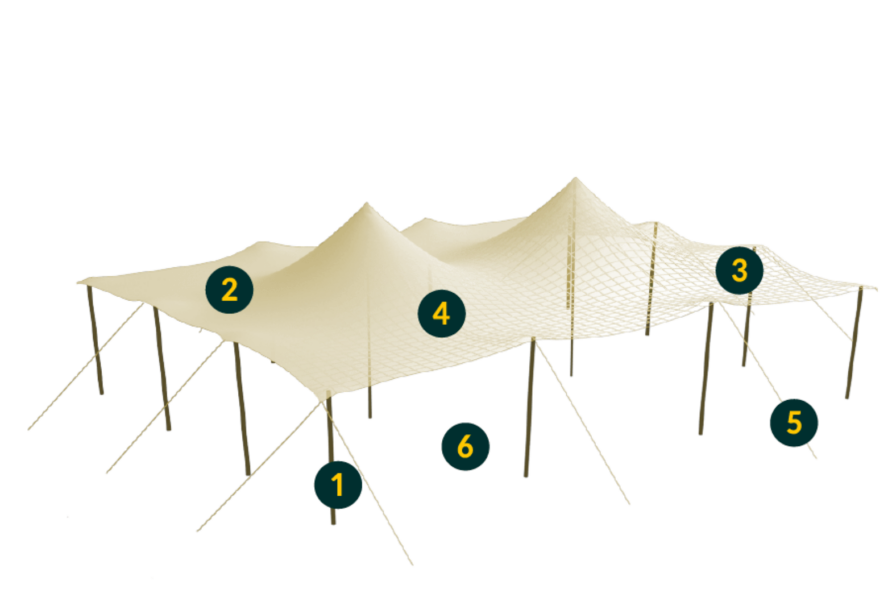

The Nixus Stretch Canopy could be adapted for C-UAS mesh.

And again, any of the tube and clamp systems I have covered in this series.

Urban Areas

In an urban environment, larger areas might require protection, e.g. across a street.

Battery operated power tools are the obvious answer for fixings, and the British Army uses Makita, an 18v DHR171Z 18v SDS+ Plus drill weighs less than 3 kg with a battery. With a small range of drill bits and fixings, this would be a flexible and capable option.

A quicker option would be powder actuated impact tools.

These generally use .22 or .27 blank rounds of different strengths to provide the power. Ramset and Hilti are the two main manufacturers.

With many other models available, the Hilti DX2 weighs less than 2.5 kg.

Fastenings like the model below would allow nets to be quickly fixed across doorways, entries, and other openings.

At 1.4 kg, the Ramset Trigger Shot is an even lighter alternative to the Hilti DX2, and cheap enough to be semi-disposable.

These modern products (and there are many more of them) can be used to quickly fix and tension meshes and nets.

Larger flexible mesh panels, with integral steel wire rope, can be attached to these fixings, and tensioned using various methods.

Carabiners and other fixings can also be used.

Where the mesh is light enough, even cheap plastic clips can be used.

Counter Drone Nets — Discussion

We already have in service, in abundance, the most snaggy thing on the planet.

Cam nets make perfect drone nets, if the defeat mechanism is ensnaring an exposed rotor.

We even have popup shelters in service.

The question is, are these enough?

It must also be observed that whilst there is an enormous investment in Counter-UAS detection and weapon systems, from handheld devices

to vehicle mounted weapons.

Investment in passive systems, like multi-spectral camouflage and nets and screens, seems much less visible from outside. This is understandable, lasers are interesting in a way that nets are not, but it would be good to hear more about investment in other areas.

Back to the nets.

What type of loitering munition, UAS or UAS dropped munitions does the net need to defeat?

If the answer is a lightweight armed FPV with exposed rotors, lightweight plastic netting with 100 mm mesh size might be enough.

Dismounted infantry in more open terrain or woods (without many vertical openings to protect), any C-UAS net has to be as light as possible and quick to deploy at a halt, but able to provide a bubble. A larger net might be a better option here, with simple fixings and tensioning systems in a stuff sack.

For vehicles at rest, I’m quite in favour of four Rolatubes at each corner, with clip on mesh panels and attached guy lines. This would allow the crew to rapidly put up a C-UAS mesh when at the halt (and might work equally well with multispectral camouflage)

Fixed defences would benefit from any of the lightweight solutions described above, especially during initial development, before the personnel building them have time to get under cover and build more robust counter UAS defences.

The most obvious net to use is whatever camouflage nets are already in service, a bit of a no-brainer to utilise them more widely for fighting positions and shelters.

And if we can upgrade to multispectral, even better.

Beyond the simple defeat method of rotor entanglement, higher strength nets will generally require greater tension to provide a suitable physical barrier. Greater tension and stronger nets lead to a requirement for stronger fixings and tensioning fixtures, together with frame systems.

Rigid mesh (like security fencing) requires no tension, although it will typically require some frame if freestanding, and these will be largely less convenient to carry. Freestanding fence panels may also require some tensioning like guy lines to remain in place.

In Ukraine, methods for defeating larger and heavier drones and loitering munitions appear to centre on rigid steel mesh panels or chain link over a steel frame, whether in vehicle slots and larger field shelters.

Heras fencing would appear to be a useful alternative option, or galvanised mesh over a scaffold or steel tube and connector frame system.

These are cheap, readily available, likely to be quite effective, and easy to deploy, even without skilled personnel.

Any of these would be versatile, not vehicle or shelter specific, a kit of components that could be adapted to suit evolving requirements and environments.

The main problem with these is they have a high metal content that would likely provide a distinctive radar and thermal signature.

Great as an expedient, but arguably a technical dead end.

Low metal content solutions would be better to explore, Tarian and GRP tube and clamp systems would seem to be ideal.

The big metal vehicle would still require some means of concealment, of course, using multispectral camouflage, the two are complementary.

To summarise, I think we should first focus on concealment and camouflage, and utilise modern multispectral systems. But then, start to look at ultra-lightweight solutions for dismounted infantry and initial stage field defences.

Beyond that, low metal content systems like Rolatube, GRP Kee Klamp, and Tarian, for larger shelters.

None of these will break the bank, and yes, Explosively Formed Projectiles and Thermite are another problem, but that doesn’t mean any of the above options are moot, it is just another problem to solve.

As with all these solutions, optimal combinations would come from study and practical testing.

Thank you for article

Ex 11th Hussars & Kings Royal Hussars

Not to be negative, cheap and simple has a lot going for it, but one flaw to my mind is these devices won't provide any protection against Self Forging Projectiles…which are small enough to be fitted to your typical FP drone. Such war heads aren't suitable for every application either.

It’s always going to be a reaction game, one side counteracting the other 🤷🏻♂️

AmSafe Bridport's Tarian RPG netting should be a suitable replacement for steel mesh/fencing.

I was talking about Tarian the other day in this context Paul, but I have obviously forgotten to include it here. Good shout, will do an edit and include.

I have been wondering about umbrellas for a while now both for drone defence and for thermal cover too.

Sounds like a neat idea

Thanks, It poses more questions than it answers and i like that. There is no panacea, so the threat assessment and understanding the risk appetite is crucial.