Light role forces that exploit the speed and reach of helicopters face the reality that when on the ground, they are the opposite of having speed and reach.

Once landed, they are on foot.

Repeatedly, military history has shown the value of small groups of well-trained, fit, and determined soldiers or marines on foot.

However, the amount of military equipment and sustainment stores they can carry will always be limited, and whilst this can be extended by aerial (including uncrewed) resupply, it has a naturally limiting effect on utility.

Therefore, vehicle mobility for these should be a consideration.

Where would such a force be used, what would they be used for, who would they be?

These are all fair questions, but fair questions I am going to push out to the end.

Why Helicopter-Carried Vehicles

In general terms, there are three reasons why helicopter-carried vehicles are useful.

1, Area Held at Threat

In general terms, there are three reasons why helicopter-carried vehicles are useful.

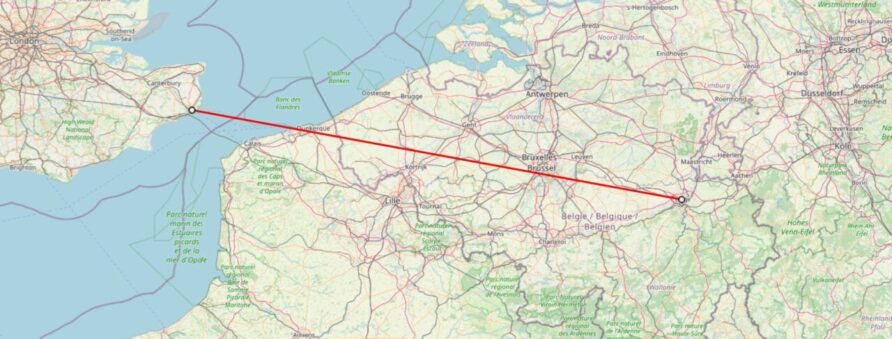

After yet another mayonnaise-on-chips outrage, the UK decides it has had enough and decides to invade Belgium. Four helicopters take off from the White Cliffs of Dover and fly 300 km to Liege, landing on the Province Naimette Arena

The landed force can either walk or drive.

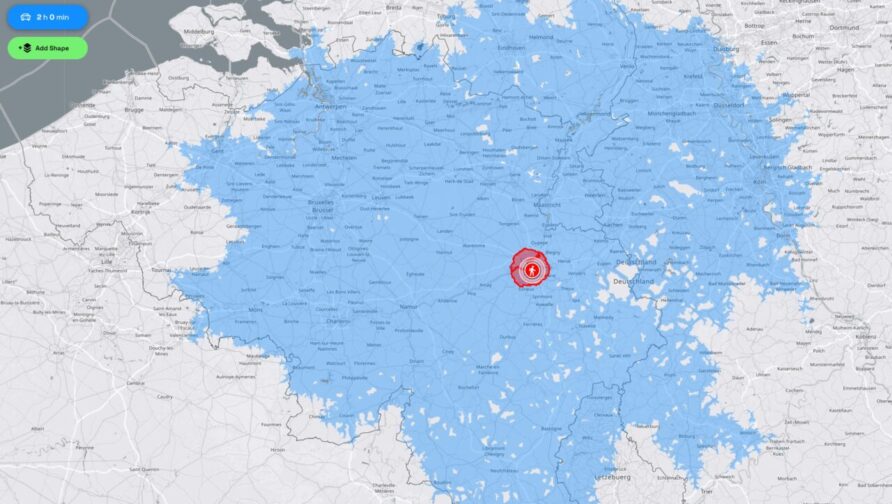

The image below shows a 2-hour isochrone (travel time) map that displays two modes of travelling, marching (red) and driving (blue).

Belgium has an extremely high road density and high-quality roads so the difference between red and blue is maximised, rural areas and poor terrain would look different.

A simpler technique that uses travel time and speed to derive an area of a circle produces the following results.

- 5kph marching speed, 2 hours travel time results in a circle of 315 km2

- 40kph driving speed, the 2 hours of travel time results in a circle of approximately 20,000 km2

Using either method, I’m sure you can see the point.

Military Useful Load

Marching means everything must be ‘man-portable’, sustainment stores will be limited, and there are unlikely to be any heavy weapons.

Without vehicles, there will be more personnel, but their reach and range of effects will be limited.

Using vehicles will result in a heavier but smaller force, with a greater range of capabilities and longer endurance.

Air Defence and Detection Stand-Off

One of the most significant trends in the employment of support helicopters in air manoeuvre is the increasing proliferation and capability of air defence systems.

Helicopters are not the fastest aircraft and will be even slower if carrying an underslung load.

The odd MANPADS and 23 mm automatic cannon-armed technical in Africa is one thing, but a modern integrated Russian air defence system in Eastern and Northern Europe is entirely another.

Long-range surface-to-air missiles are prone to radar horizon issues, especially if the helicopter is flying at extremely low altitudes and using terrain masking.

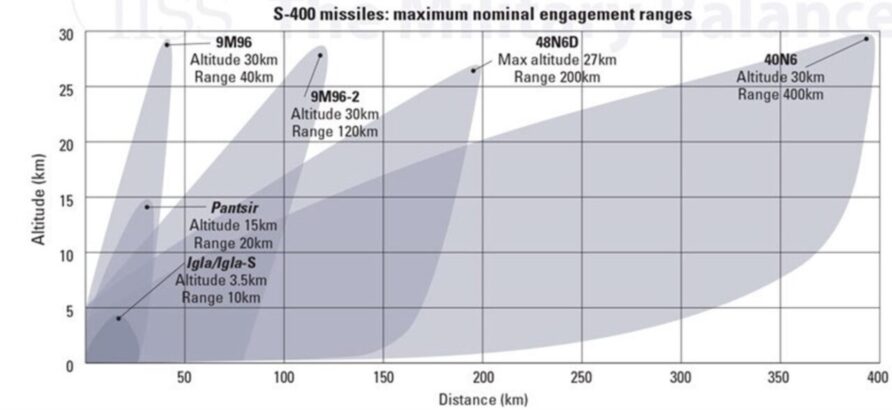

This diagram from IISS is a useful illustration of how a layered point defence system pushes aircraft to greater ranges and lower altitudes if they wish to remain undetected.

175-200 km stand-off range at less than a couple of thousand metres altitude may provide some measure of survivability, but it also means that distance must be covered, on foot

With vehicles, it becomes a 3–5-hour drive.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Underslung or Internal Load?

If the section above illustrates three potential advantages of using helicopter-borne vehicles, the next decision point is whether they should be carried as an underslung load or inside the cargo hold.

Underslung

Since we have operated helicopters, we have used them to carry vehicles as an Underslung Load (USL)

And more recently, likewise

It is entirely normal.

Normal does not make it simple.

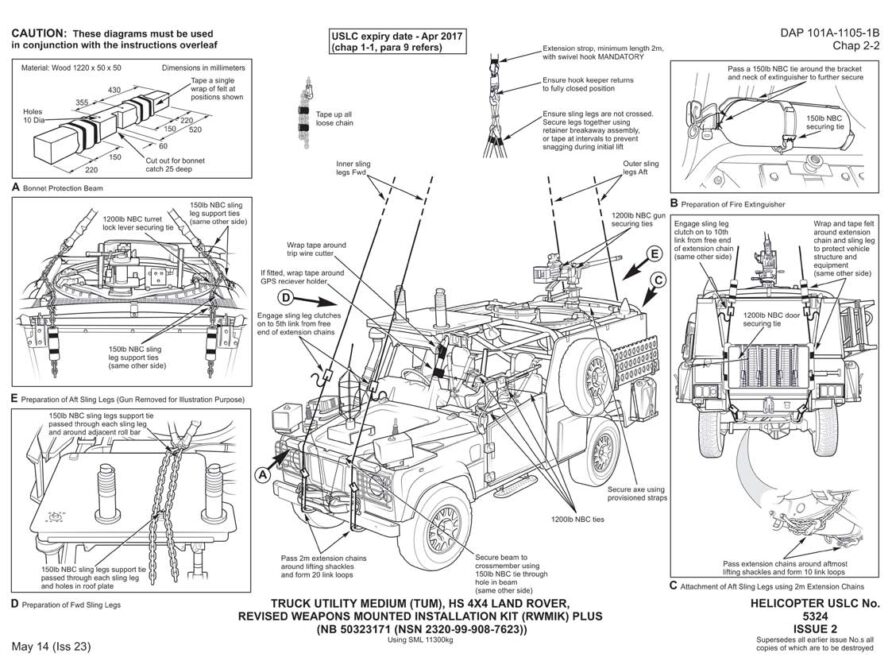

For all the combinations of helicopters and vehicles, there is an Under Slung Load Clearance document.

The document holds information such as rigging and de-rigging procedures, an illustration, and a list of the strops, slings, spreader bars, nets and other equipment, generally known as Helicopter Underslung Load Equipment or HUSLE.

The diagram makes clear that rigging and de-rigging procedures are not quick or easy.

The document also holds Flying Characteristics and Limitations.

Flying Characteristic Limitations include the Indicated Airspeed, Angle of Bank, and Rates of Descent.

Simply put, when a helicopter is carrying an underslung load, it will not be as fast or agile as if it weren’t.

A Chinook’s top speed is approximately 170 knots, but with an unladen Land Rover (TUM) it is reduced to 50 knots and with a Land Rover RWMIK, 110 knots.

Despite the Merlin having a safe working load on its hook of 5,443 kg, and the Chinook, 11,300 kg, carrying vehicles on them is a compromise, principally, time into action on the ground and performance limitation on the aircraft.

The Merlin is likely to be more readily available for the Royal Marines than the Chinook, although the Chinook has been used on plenty of commando operations in the past. But as amply illustrated in the image below, because the Chinook does not have any blade fold, it takes up at least twice the space of a Merlin, if not more.

Vehicles can be driven onto the helicopter in the hangar, moved to the deck and quickly flown off the vessel.

Rigging an underslung load requires time and space on deck, both precious commodities.

Internal Carriage Dimensional Constraints

Aircraft performance and time at the departure and arrival locations are why carrying vehicles internally is attractive, but there are some downsides when compared to carrying them as an underslung load.

Mainly, the lack of space.

Not only will vehicles carried inside will displace personnel, but dimensional limits also constrain them.

To carry a vehicle inside a Merlin or Chinook is to accept it won’t be big.

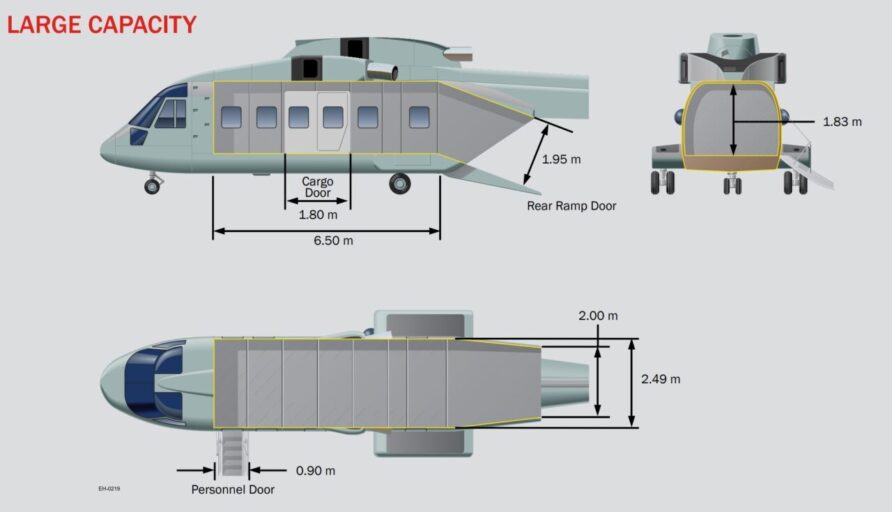

From the diagram above, the internal constraining dimension is the ramp width, at 2.00m, and height, at 1.83m

| Helicopter | Width (m) | Height (m) | Length (m) |

| Merlin | 2.0 | 1.8 | 6.5 |

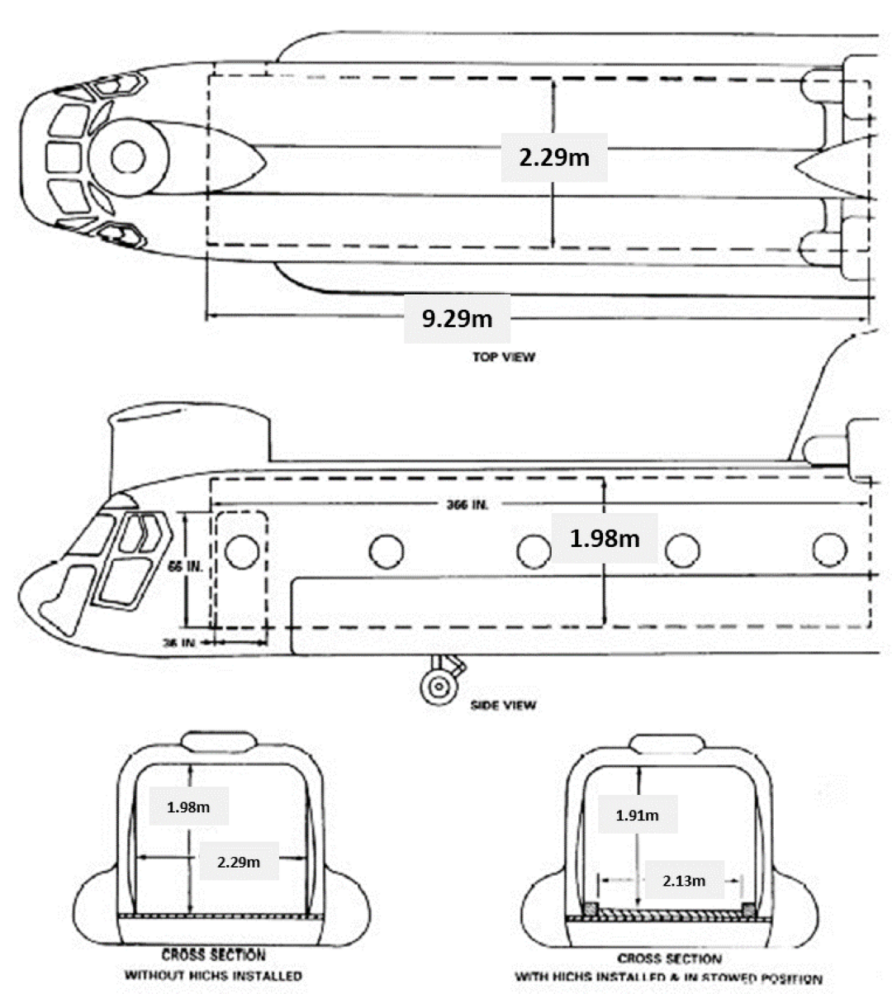

The Chinook is a larger aircraft with a higher lift capacity.

With Chinook, there are variations in cabin dimensions depending on internal cargo handling fittings, being conservative and taking the lower figures.

| Helicopter | Width (m) | Height (m) | Length (m) |

| Chinook | 2.1 | 1.9 | 9.3 |

Other helicopters that might also be considered for reference are.

| Helicopter | Width (m) | Height (m) | Length (m) |

| NH90 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 4.8 |

| Mil 8 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 5.3 |

| CH-53K | 2.7 | 1.9 | 9.1 |

| V-22 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 7.4 |

V-22 is quite similar to Merlin.

Other Issues

It is tempting to assume that if vehicle dimensions < cabin dimensions, it is good to go, but this is not the case.

Seating arrangements, differences between the ramp and internal hold dimensions, ramp break-over dimensions, cargo floor equipment, lashing arrangements, vehicle specifics, access to side doors, means of escape, safety restrictions and other internal obstacles might ultimately result in a vehicle being unable to fit inside.

For smaller vehicles, if they can fit, these restrictions might also mean a smaller number can be carried.

Finally, the closer a vehicle is to the constraining dimensions, the more difficult and slower it will be to load and unload.

This could be a significant issue if a vehicle takes 20 minutes to unload because it is so tightly packed that it exposes the aircraft and personnel to detection and enemy fire.

When looking at any vehicle’s suitability, the amount of ‘room’ it has will be considered.

This stuff is the work of professionals, not random people from the internet (me) so any suggestions I make in the following posts should have a health warning, subject to confirmation by people who know what they are talking about.

In the rest of the series, the vehicles described will have to be in production and adapted with only simple engineering changes such as fitting a folding roll bar or windscreen.