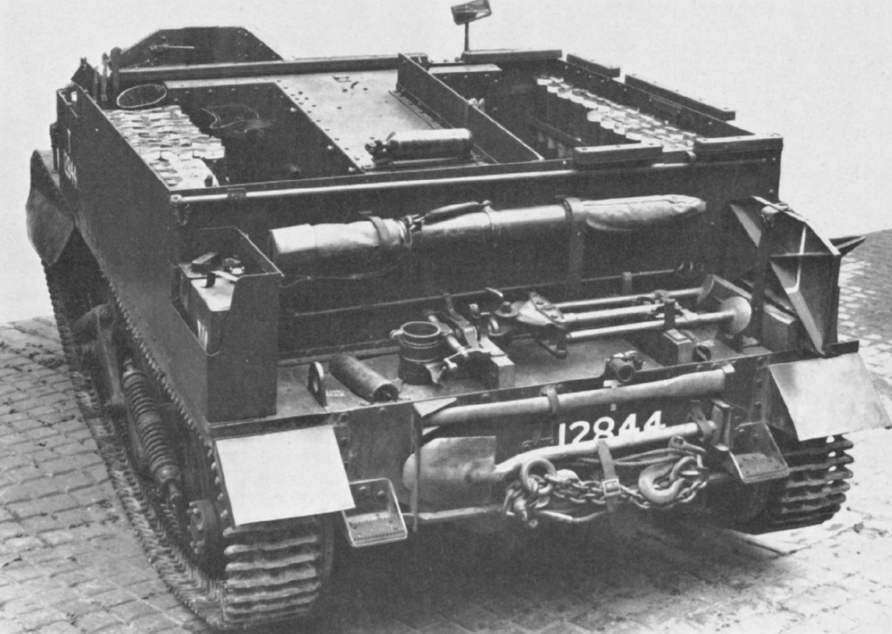

The Bren Gun Carrier, or Universal Carrier, was a class of WWII-era vehicles unique to British and Commonwealth armies used for logistics and support weapon carriage.

As you all know, the concept was invented by Giffard Le Quesne Martel, a famous Sapper also responsible for parts of the Bailey Bridge.

The story of the progression from the Machine Gun to the Universal Carrier is actually a complex one, outside the scope of this post, but by the end of WWII, it was the most numerous British Army armoured vehicle, with some 100,000 made, and production only ending in 1960.

Intended to eventually be withdrawn in favour of the Oxford Carrier, the end of WWII saw those plans changed, and eventually, through the FV200 series of vehicles, the FV432 we know and love today replaced it.

It weighed approximately 4 tonnes fully loaded, 3.7m long and 2.1m wide, with a top speed of just under 50kph.

Skip forward to 2023, is there an argument for something similar?

If I said no, this would be a very short post!

Why Do We Need It?

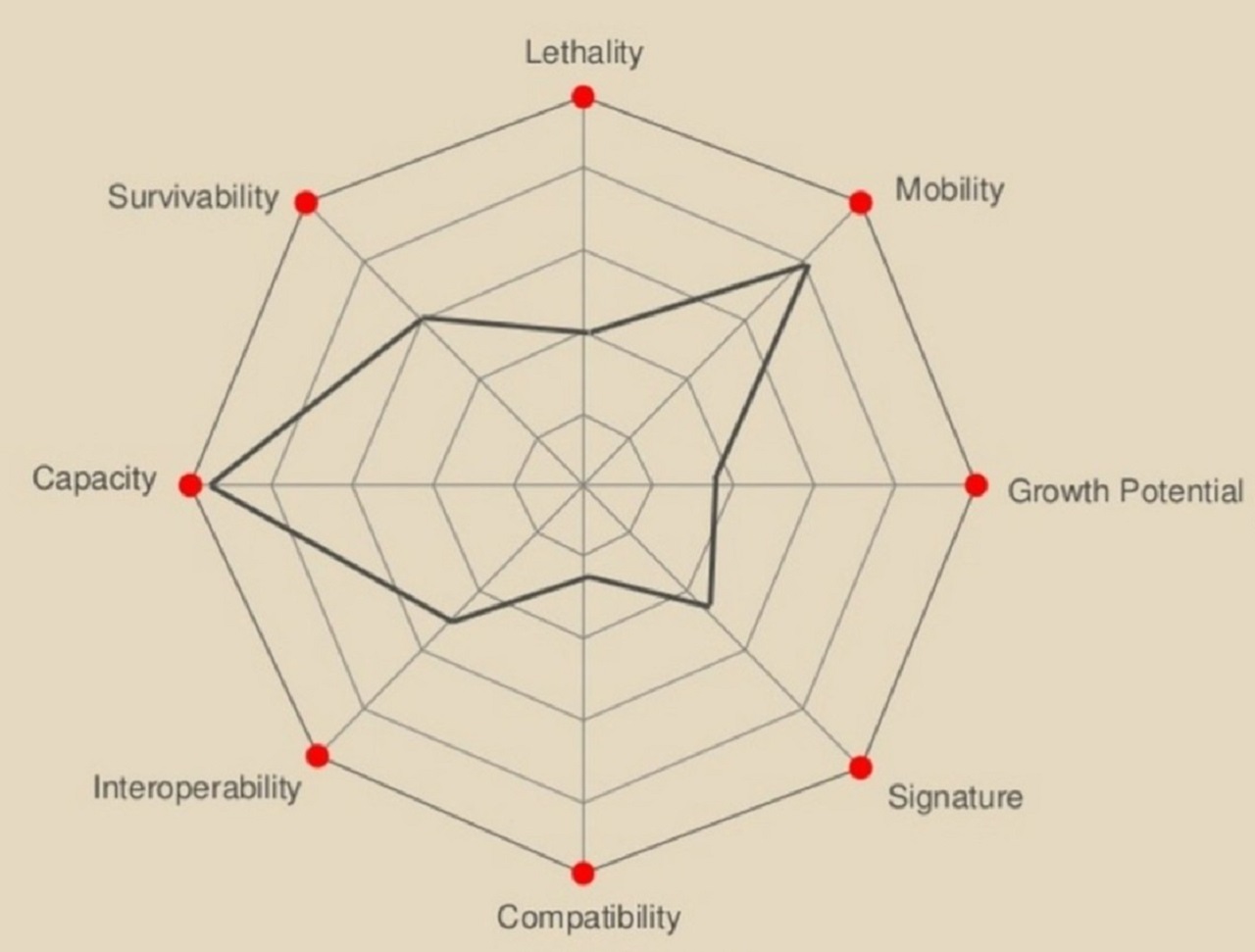

In a crowded equipment programme, every last nut and bolt needs to be aligned with a specific requirement, put simply, UC23 would provide high mobility load and personnel carriage in extremes of terrain.

Operating Areas and Terrain

Ukraine has focused the British Army on conventional operations supporting NATO in Eastern Europe and the High North.

These two operating environments are where much of the future of the British Army will rest (although not all of it)

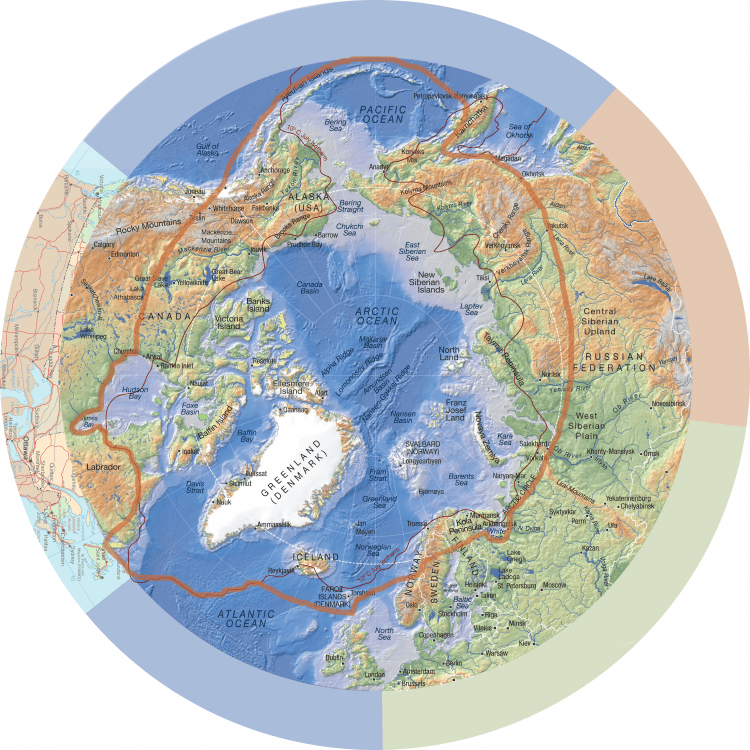

The High North was a term coined by Sverre Jervell, a Norwegian diplomat, in 1986 in a book called The Military Build-up in the High North.

Although not defined in the book, it has subsequently been used to describe an area that spans the Arctic (a clearly defined area) and includes references to both climate and geography. For example, a climate definition is those areas to the north of a line with a specific median July temperature, others include an area to the north of the southern limits of maximum sea ice or the tree line. The Arctic Council Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) uses a hybrid definition based on multiple factors.

The term also has a clear political aspect, and the Norwegian Government a few years ago attempted to put it in context.

The High North is a broad concept, both geographically and politically. In geographical terms, it covers the sea and land, including islands and archipelagos, stretching northwards from the southern boundary of Nordland county in Norway and eastwards from the Greenland Sea to the Barents Sea and the Pechora Sea. In political terms, it includes the administrative entities in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia that are part of the Barents Cooperation.

A Defence Select Committee report, also a few years ago, had this as its working definition;

‘European Arctic’, roughly stretching from Greenland in the West to the Norwegian/Russia border in the Barents Sea in the East, and encompassing areas of strategic importance such as the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) Gap and Svalbard.

Whilst the definition of the Arctic Circle is clearly bounded by geography, the concept of the ‘high north’ is less so, this hasn’t stopped people from trying to map it, one example below

China achieved ‘observer’ status on the Arctic Council in 2013 and Russia has been a long-standing member. Both are hostile to our interests and that of our allies. The UK has also been an observer since 1998 and although the Arctic Council was originally intended to avoid matters of security, it is difficult to see that enduring.

Climate change may result in a reduction of Arctic ice, and this will inevitably result in greater access and economic exploitation. This exploitation will likely result in increasing political tensions with the potential for conflict.

The fact remains, whatever the definitions, it is on our doorstep and includes friends, allies and potential enemies.

The Select Committee report concluded;

As the ‘globalisation’ of the region continues, an increasing number of states which are more geographically distant from the Arctic are declaring that they have an interest in Arctic affairs and wish to share in the benefits which might come from a more accessible Arctic. This is to be welcomed, as long as these interests continue to coincide. We should nonetheless be aware, in this new age of ‘great power competition’, that this state of affairs may not last indefinitely. The Government should work closely with allies to establish a common position on all aspects of international law in the Arctic to ensure that disputes active among states in the region are not aggravated or exploited

If the British Army is to concentrate on the High North and Eastern Europe, as many advocates and is the general direction of travel, terrain accessibility becomes critical.

The terrain in the high north is incredibly complex and varied, it is not just deep snow in the winter and mud in the summer, but what characterises them most is their very low bearing strength.

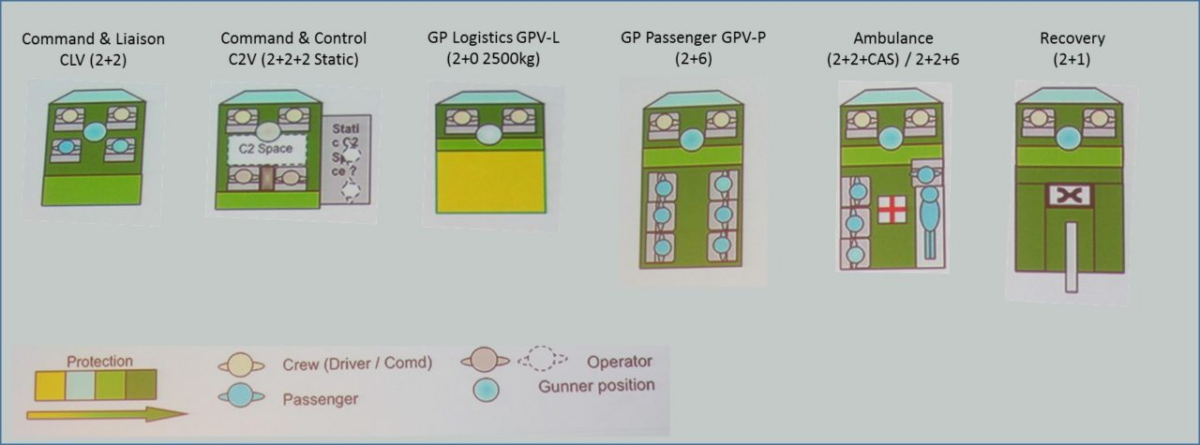

Multi-Role Vehicle Redefined

The Multi Role Vehicle – Protected (MRV-P) was a large project from 2012 to bring into service two protected-wheeled vehicles that would replace many UOR vehicles.

A Category A project intended to meet the requirement for a protected deployable platform employed by all Force Elements, at all scales of effort, in a wide range of environments, and on all parts of the battlefield except for the direct fire zone. The MRV-P should bring commonality to the fleet and reduce the logistics footprint for utility vehicles by 2020.

MRV-P had a very long backstory (don’t they all), going back to the Operational Utility Vehicle System (OUVS) programme from 2003, in reality, we were a decade from the original requirement, two if you include OUVS.

Roles were to include;

- Command and communications post vehicle

- Command and liaison vehicle

- General-purpose vehicle – cargo

- General-purpose vehicle – passenger

- Light gun towing vehicle

Even at this stage, the requirement for MRV(P) was specified as a Military/Commercial Off the Shelf (MOTS/COTS) vehicle platform(s), with no development.

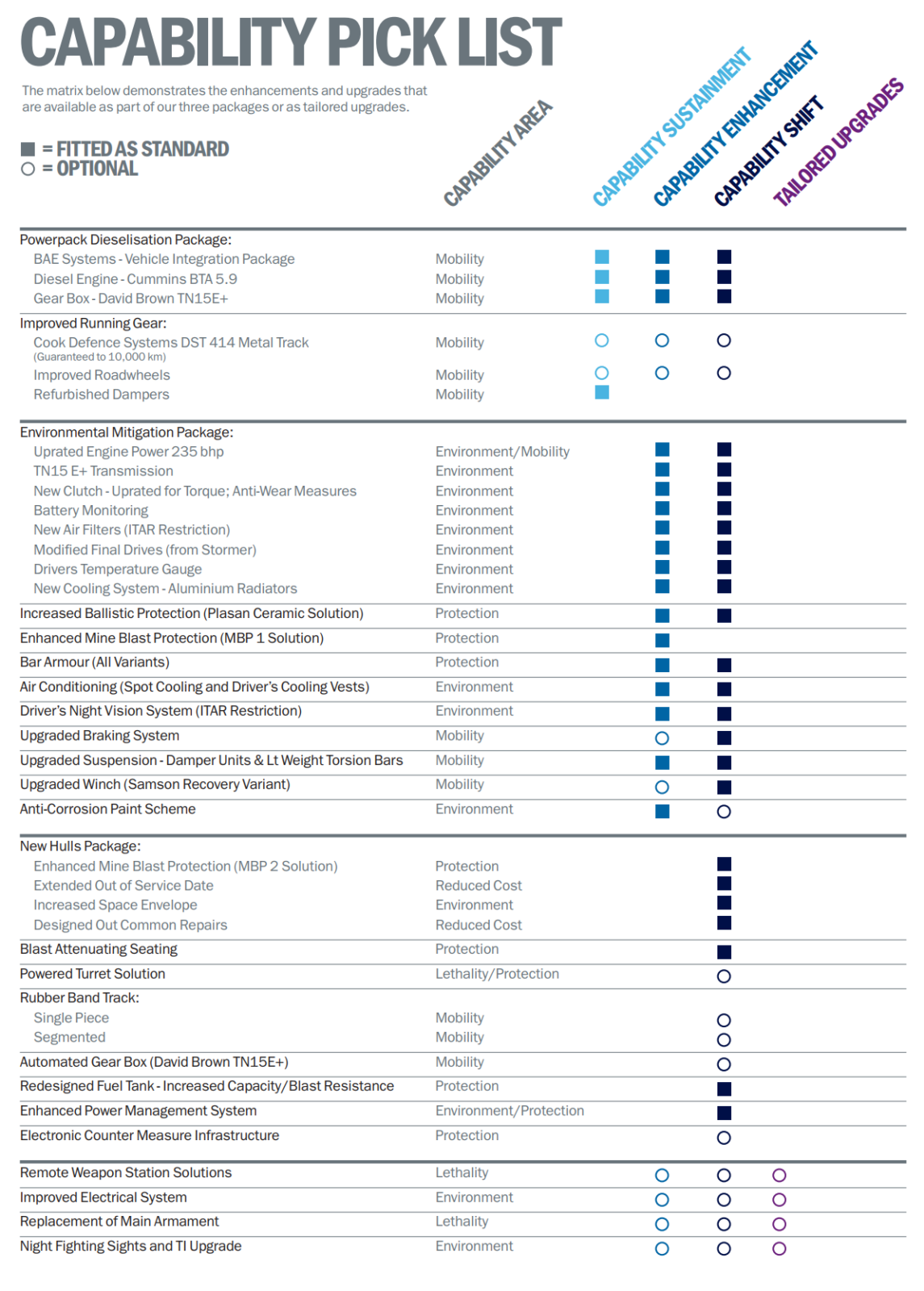

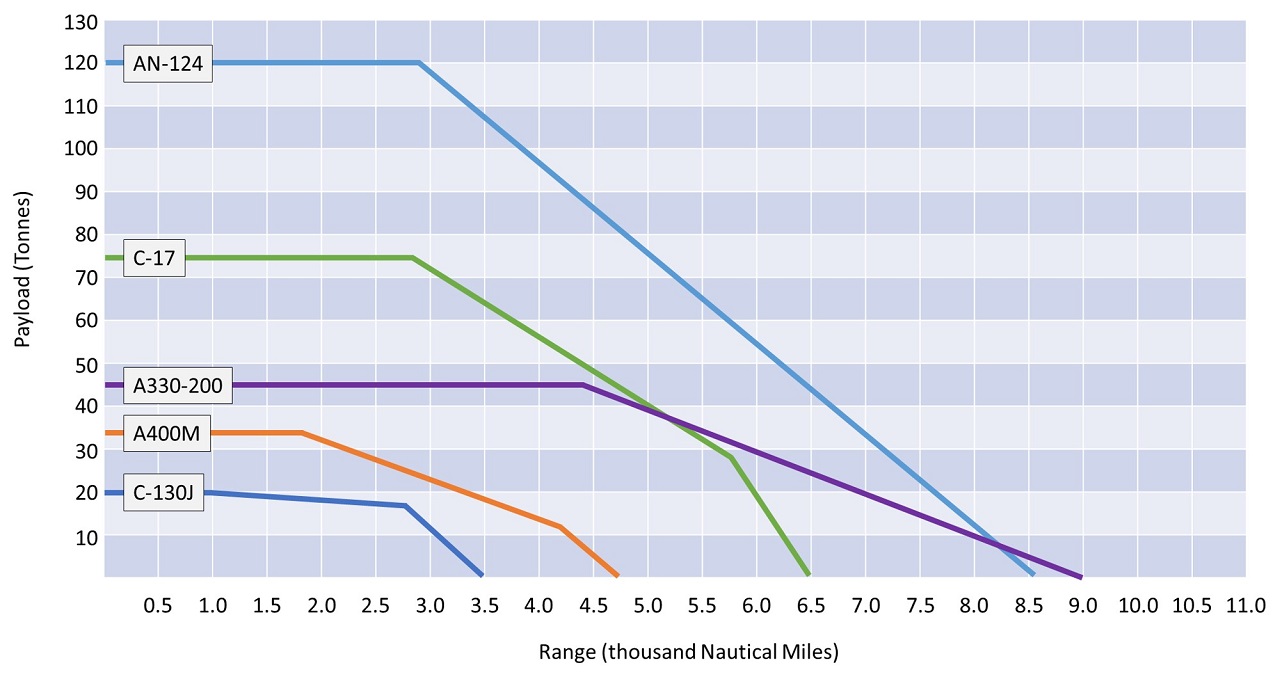

The payload was defined as greater than 2.5 tonnes, with a maximum unloaded weight of 14 tonnes or 10 tonnes if transported by C-130.

The turning circle was specified at less than 18m, compared to 14m for a Land Rover. The maximum width was 2.5m and mobility was defined as ‘Medium’, not ‘Improved Medium’. Mobility was further defined by a ground clearance of greater than 240 mm and ground pressure of less than 450Kpa.

Generic Vehicle Architecture 2 compliance and the ability to be fitted with ECM, BOWMAN and an RWS.

A lot of water has passed under the bridge since then, but before its quiet shelving, the preferred options were the Oshkosh Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) for the smaller variant (package 1), and either the General Dynamics Eagle or Thales Bushmaster (Package 2) for the larger variant.

Both are fine vehicles, but can you really see either of them plugging through that mud above?

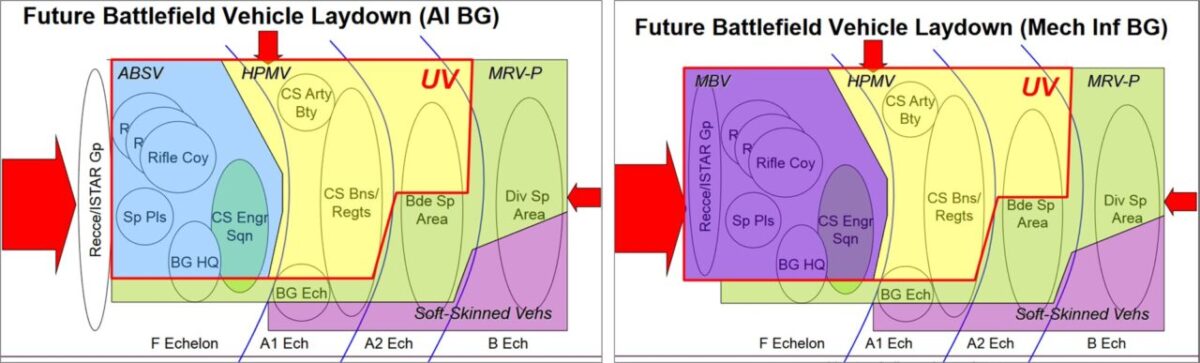

One of the problems I think MRV-P suffered from was its intended ubiquity, it would be everywhere on the battlefield, and used across 1 DIV and 3 DIV operations.

i.e., it would be cutting about facing the Russians in Estonia as well as some ISIS-inspired Jihadis in Africa.

Was this too much for a single-vehicle or vehicle family, I think so.

This leads me to the thought that MRV, or whatever rises from its ashes, needs to be in two flavours, wheeled and tracked.

I do, of course, recognise the inherent contradictions here, 3 DIV will have Boxer, it has many trucks, and 16AAB is also not mentioned, but I hope you get the point I am trying to make.

I am going to forward an argument for a modern-day Universal Carrier (UC23) to meet a requirement somewhat analogous to that of MRV-P in three parts;

- ONE – Transportability Matters

- TWO – Mobility Matters

- THREE – Utility Matters

As usual, I will look at a range of civilian and military designs to meet the basic requirement.

ONE — Transportability Matters

You often hear me banging this same drum.

It is a statement of the obvious, but unless a force can move to where it is needed in a timely manner, it cannot be of much value.

Deployability is an essential component of capability and deterrence and is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as

(of soldiers and equipment) able to be moved to a place where they can be used when they are needed

Soldiers and equipment need vehicles for the most part, and so vehicle mobility is a key building block of deployability. If a vehicle is too large or heavy to use a particular mode of transport, it may be of less use to operational leaders and provide decision-makers with fewer options.

Mobility can be further broken down by category, ground pressure, turning circles, fuel consumption, gap crossing, approach and departure angles, traction, flotation, fording ability, or the hundreds of other design criteria that determine a vehicle’s strategic and operational mobility.

Transportability is defined as…

Transportability is the inherent capability of material and units to be moved efficiently by existing or planned transportation assets

Transportability is important for everything from light role infantry to armoured.

There is little point in having a rapid deployment force whose main feature is the ability to exploit the speed and reach of air power if its vehicles and equipment are too big or heavy to use the most common aircraft readily available to it.

Wilfred Owen makes a good argument for transportability in a 2016 RUSI Journal article

Much of the discussion on mobility has been hampered by the way the concept has been understood. Western military doctrine and academic studies have tended to address mobility in three categories: strategic; operational; and tactical. In other words, conventional conceptual understanding of mobility is strongly aligned to the levels of war. This way of thinking is not fit for purpose. As such this article proposes four alternative categories; transportability, marching, obstacle-crossing and protection as a more appropriate lens through which to understand the idea of mobility.

Transportability is defined here as the ability to move a unit, formation or force in or on other vehicles, such as ships, aircraft, rail or road vehicles (transporters). Marching is the ability to move long distances by road at an effective speed and with relative security. Obstacle-crossing is the ability of individual vehicles to surmount a set series of obstacles or move over various surfaces and inclines. That may include amphibious capabilities.

It doesn’t matter whether we are talking about an e-bike or an MBT, there are virtual ‘loading gauges’ they must pass through to be useful.

Transportation equipment and the built environment will determine what these loading gauges look like.

Whilst we can mostly define transportability in terms of weight and dimensions, as with many similar subjects, it is more complicated than that. Axle weights, G loading and tie-down arrangements are just three subjects that will influence whether vehicle A can travel inside Vehicle or Aircraft B.

For reasons that will become obvious later in the post, I am going to use CVR(T) as a reference point for discussions on transportability.

What we don’t discuss enough, is the secondary (and maybe even unofficial) roles that CVR(T) performed in the past. Thirteen years ago, I wrote a post about this, how CVR(T) had turned up in all sorts of places and been used for all sorts of things that were not its primary role.

It did these things exactly because of its transportability.

Imagine a vehicle that weighs just under ten tonnes, and can fit inside an ISO container, called UC23.

Road

Keep weight and size modest, and you can use in-service or civilian transport vehicles to move UC23 strategic distances, in singles or pairs.

Ukraine is exploiting this.

Containers

Being able to exploit the global container shipping infrastructure provides many options for deployment.

Rail

CVR(T) Spartan can be easily carried on rail flats, anywhere on the UK network.

The higher roof Samaritan, for example, tends to require a ‘warwell’ dropped deck rail wagon, but even with this, they remain easily transportable across UK, European, and global rail networks.

Aircraft

Although we plan to have C-130 Hercules leave service, replaced by A400M, many of our allies remain firmly committed to it. C-130 transportability is a desirable characteristic, especially for high-readiness forces.

A Spartan is easily carried on a Hercules.

A 10-tonne vehicle of similar dimensions to Spartan can also use air despatch platforms for parachute forces.

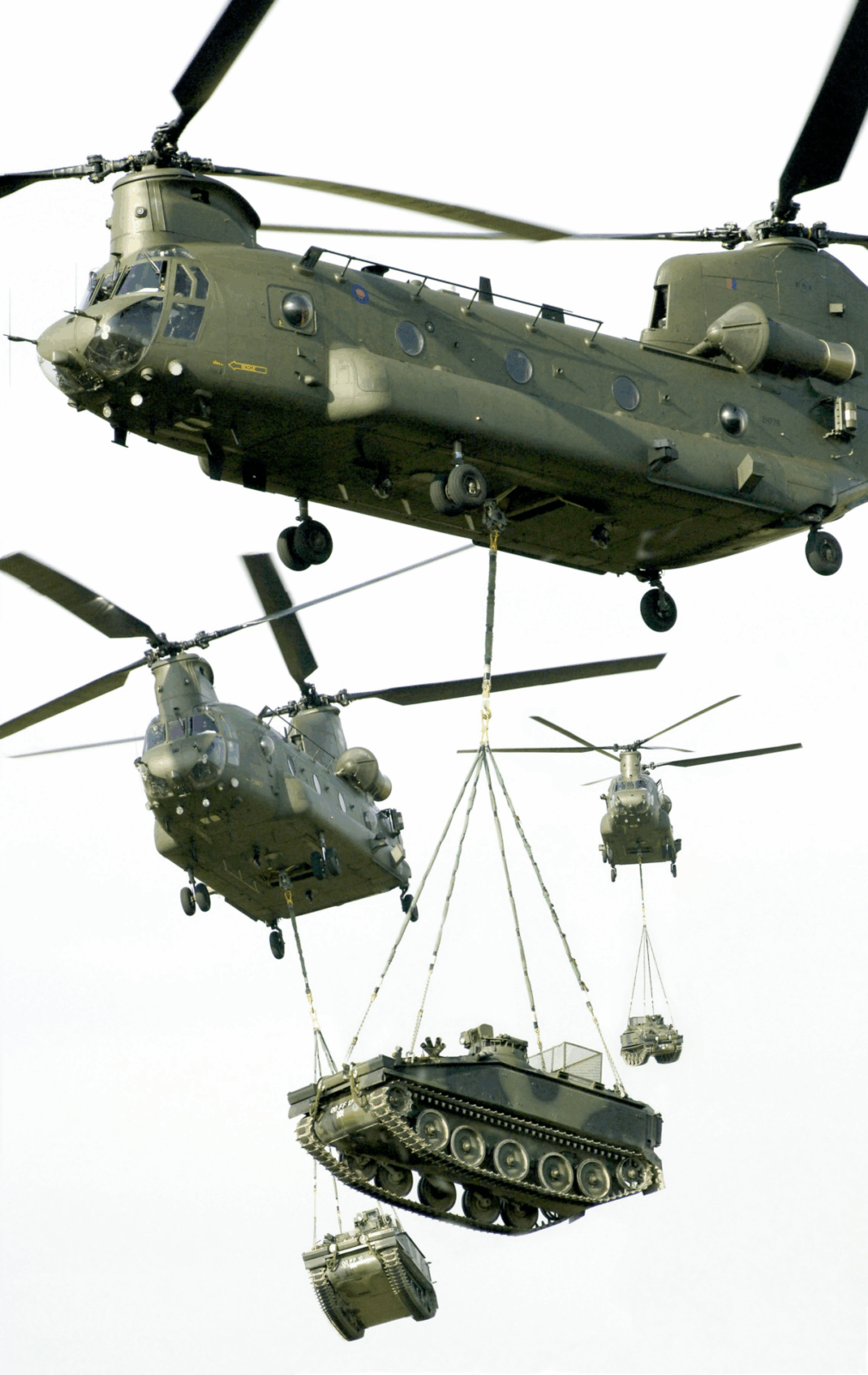

Helicopters

Internal carriage in a Chinook imposes many dimensional constraints and could be argued is a highly specialised requirement, but carriage as an underslung load has been used operationally several times with great effect.

It is also important to note that something like a JLTV doesn’t need a trailer (although it would still likely use them), it can self-deploy at range.

TWO — Mobility Matters

There is no reason why you cannot have a wheeled vehicle that sits inside a container and can be transported by Hercules or Chinook.

But, I will argue that mobility favours tracks for this requirement.

In Owen’s RUSI piece, this would be marching and gap-crossing capability.

Any vehicle can get stuck in mud and snow, tracked or wheeled, but whilst modern wheeled vehicles with electronic traction control and centralised tyre inflation systems are much more mobile than many think, physics is still physics.

And for this, tracks win, they just do.

You have probably all seen this video.

I think Boxer is brilliant, and it has much better mobility than your lying eyes might see above, but one cannot deny speed over poor terrain and gap crossing favours tracks.

Another video you might not have seen, but also illustrative.

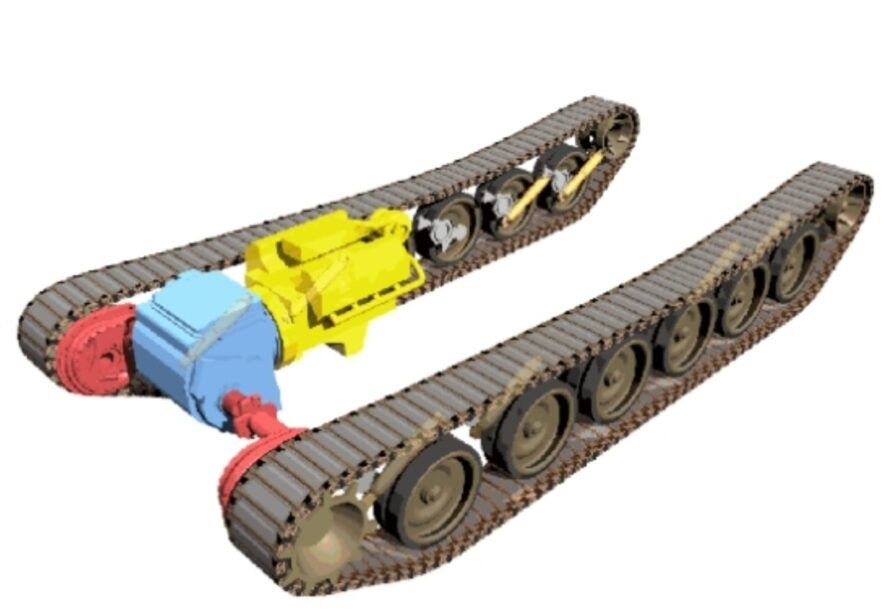

Tracked vehicles actually have a pretty simple drivetrain, especially compared to 4×4 and 6×6 wheeled vehicles.

There are downsides to the tracks themselves, the relative complexity and maintenance especially, with noise and vibration additional issues. Soucy Defense (and others) have now proven the benefits of Continuous Rubber Tracks in construction plant (where they are now commonplace) and military vehicles, including Warrior, CV90, and CVR(T).

Reduced noise and vibration, higher speeds and lower fuel consumption are all demonstrable benefits of CRT.

Height can be an advantage, but it can also be the opposite, especially for concealment and transportation, tracks allow the vehicle to be lower

Without getting too far into the never-ending tracks v wheels debate, I do think this requirement favours tracks, especially if they are rubber.

THREE — Utility Matters

Put a turret on UC23, and it becomes even less likely, it cannot be considered any kind of competitor to Ajax (or Boxer for that matter)

The value of UC23 is in what it carries, not what it does, it is not a complex fighting vehicle, it is a carrier, no more, no less, in three variants.

Variant 1 — Passenger

One could advance a case for it as a mortar team carrier (as the original universal carrier was), or for a Javelin team.

Each would only have seats for the crew of 2 and maybe 2 or 3 passengers, and their equipment.

This also reduces the personnel impact of vehicle loss.

In the interests of keeping cost and risk down, I would not propose a recovery or repair version, they would be operating in the same area as other vehicles that could recover them.

Although I am careful in this post about calling them a fighting vehicle, inevitably, arming them would be a possibility.

Using the same Thales/Kongsberg Protector RS4 as Ajax and Boxer would make a lot of sense, or even dig out the Selex Enforcers from Panther if any of them are still left in service.

This provides 7.62 mm HPMG, 12.7 mm HMG, and 40 mm GMG capability, with smoke grenades.

And Javelin

Excellent optics, laser designation and range finding, various stabilised weapons options with a range of short and long-range effects against various targets, add the Thales Martlet to complete the set, with an upgrade path to RS6 and whatever flavour of 30 mm automatic cannon you like.

Or keep it simple and just have a pintle-mounted GPMG or basic turret like the Odin turret used in Afghanistan.

There are plenty of options for piling on cost, complexity, and capability, or not.

Variant 2 — High Roof

A high roof variant simply provides additional working space and space for equipment, whilst still protected from the elements and light weapons.

Command, ambulance, UAS carrier, e-bike carrier/charging station, tethered drone carrier, and many others.

For the most part, any equipment would be demountable and simply clip into the vehicle power and electronic looms.

Variant 3 — Flatbed

There are any number of applications beyond a few people and a couple of pallets of stores or fuel/water containers, maybe even a handful of Brimstone missiles, loitering munitions, Exactor, or C-UAS payload.

As can be seen from the images, there is only a single driver in this configuration. They would need support from others within a unit for vehicle tasks, or compromise on load bed space.

A sub-variant with a hook lift might also be advantageous.

Bet you knew I was going to say that.

Options

Three options spring immediately to mind.

ONE — Civilian Derived Design

Generally speaking, civilian tracked load carriers will have a lower speed than dedicated military vehicles. High speed has little value in utilities, agriculture, or energy exploration markets.

Obviously, protection against bullets and artillery fragments is pretty down on the priority list for them also.

But I have included them here for completeness to demonstrate if a trade-off in these specification areas (speed and protection) was accepted.

The Canadian Alltrack AT-20HD has a kerb weight of just over 2,700 kg but with a payload of nearly 1,600 kg, has a gross weight of 4,309 kg. Closer to home, the UK-manufactured Loglogic Softrak 75 is in the same weight class, one of which is actually in use as an MoD range vehicle. It has a kerb weight of 2,550 kg and a payload of 2,000 kg, with hydraulic and hydrostatic power take-off should it be needed.

A wide range of tipping or demountable bodies can be fitted

With a top speed of 16 kph, it would take some to cover any distance but with a ground pressure of less than 2PSI, its terrain accessibility is excellent.

A larger version called the Softrak 140 is also available, upping the payload to 2,400 kg.

Other manufacturers of tracked all-terrain vehicles for use in demanding terrain include Lynx Technologies, Gilbert, Prinoth, UTV, Fecon and Powerbully, with plenty of options on the global market.

As can be seen from these designs, the track width is such that the payload sits on top, not between the tracks. This makes the overall height much greater than something like CVR(T) or Wiesel.

Tracked Dumpers are also a potential donor vehicle, usually slightly larger and heavier than those above, but available straight off the shelf from several global manufacturers.

It might be feasible to add a protected cab for any of these, but it would eat into the payload.

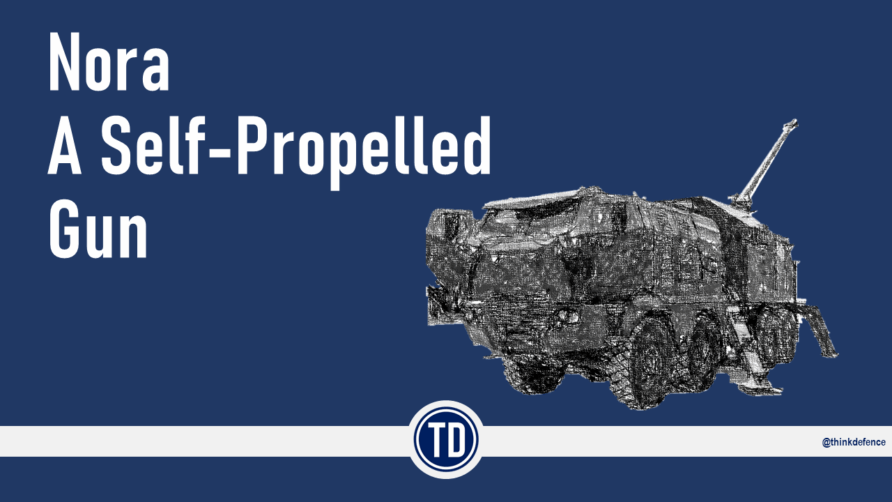

CVRT Spartan and Streaker (Mk3)

CVR(T) Mk2 vehicles were built from the ground up, with new hulls with improved aluminium alloys, each was less than £750k.

No, that is not a typo.

Continuous Rubber Tracks, and a range of other improvements

The major components are all readily available, engines, TN15E transmission, tracks etc.

Cage, laminated, technical fabric and perforated armour packages have also been developed, and are readily available.

There is even a company in the UK that will refurbish old ones (if the Ukrainians haven’t hoovered them all up)

Perhaps the lowest risk route is to simply take CVR(T) Spartan Mk2 and take a hacksaw to it, creating a Streaker.

The Streaker variant never actually entered service, but they are a simple conversion from Spartan, weighing about 5 to 6 tonnes with a 2-tonne payload/

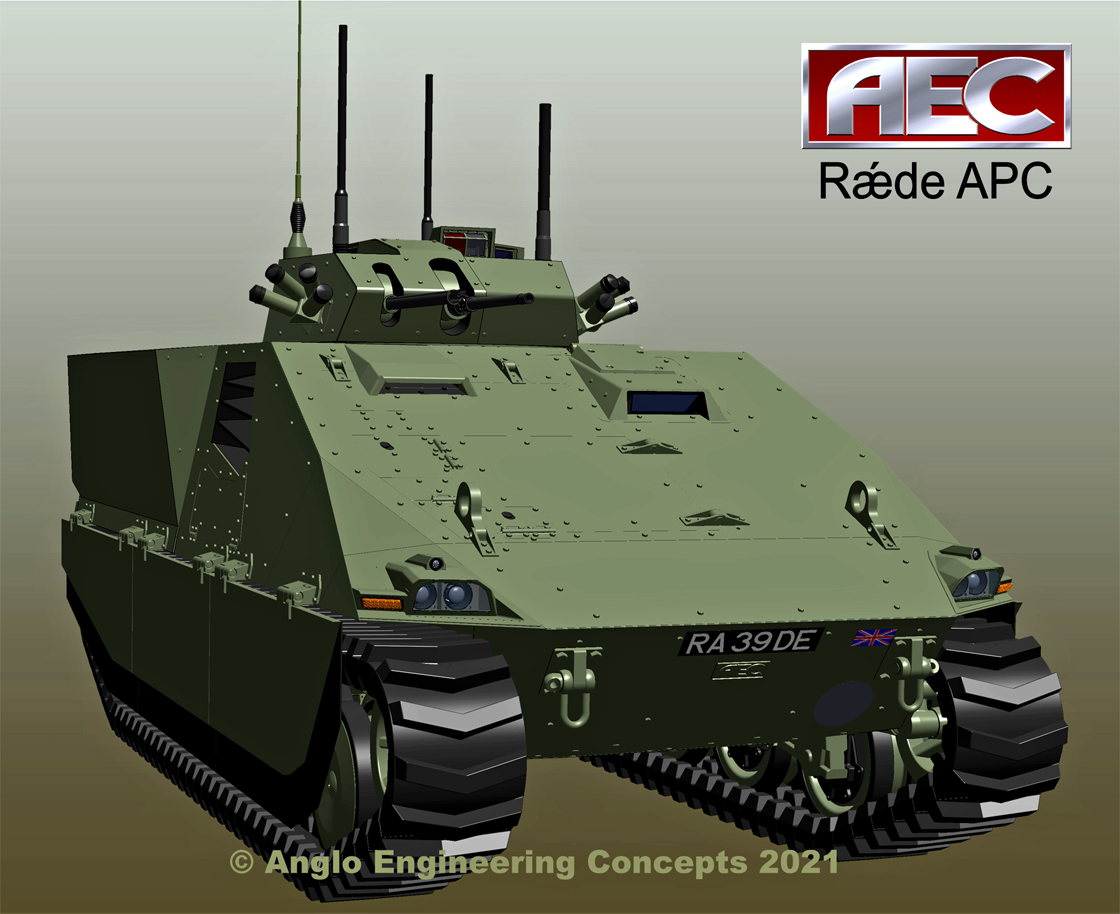

New Design

The final option would be an entirely new design.

We certainly have the component manufacturers in this country and the designers.

The British Army is currently trialling a series of heavy UGVs, from several overseas organisations.

Nothing wrong with ‘market assessment’ but is there any reason a Land Industrial Strategy focussed UC23 could not be uncrewed?

We have the onshore expertise and have Terrier and some engineering plant already in service with remote control systems from QinetiQ.

We have demonstrated Warrior with autonomous guidance systems from DCE Concepts

By building a single vehicle that can be crewed or uncrewed, we avoid small niche boutique fleets and build industrial resilience in.

Building this in from scratch is likely to be easier than retrofitting, one would imagine.

The introduction document to the Integrated Operating Concept provides some cues for UC23;

- Have smaller and faster capabilities to avoid detection

- Trade reduced physical protection for increased mobility

- Rely more heavily on low-observable and stealth technologies

- Depend increasingly on electronic warfare and passive deception measures to gain and maintain the information advantage

- Include a mix of crewed, uncrewed and autonomous platforms

- Be integrated into ever more sophisticated networks of systems through a combat cloud that makes the best use of data

- Have an open systems architecture that enables the rapid incorporation of new capability

- Be markedly less dependent on fossil fuels

- Employ non-line-of-sight fires to exploit the advantages we gain from an information advantage

- Emphasise the non-lethal disabling of enemy capabilities, thereby increasing the range of political and strategic options

Not all of these would apply, but most would.

The UK is a world leader in automotive technology, especially engines (and third in Europe by volume), the industry is twice the size of the shipping and aerospace industry combined, to the surprise of many.

It would be good to build on the great work done by the British Army and MoD with building supply chains and some measure of industrial resilience with Boxer and CR3, but there are more options to go after.

Perhaps a modest Cat D or C assessment study would be possible, combining crewed and uncrewed, and looking at fossil fuel reduction technologies (on top of the work already done in this area with wheeled vehicles);

| Category | Procurement Cost | Approving Authority |

| A | Above £400M | DE&S Investment Board, IAB, MOD Ministers and HMT |

| B | £100M to £400M | DE&S Investment Board, IAB Delegated Approving Authorities |

| C | £20 to £100M | DE&S Chief Of Staff, IAB Delegated Approving Authorities or TLBs |

| D | Under £20M | Relevant DE&S DG or IPT Leader |

The components are all there…

Summary

CVR(T) leaves a gap, especially for lighter role forces at high readiness by virtue of its non-recce capabilities, and no one I have spoken to had a bad word for CVR(T) Mk2.

The British Army need to build credibility; Boxer, Ajax and CR3 might eventually go some way to restoring this credibility, but a low-risk sovereign build programme like building a UC23 is a stepping stone, and it all matters.

It also requires a very specific mobility v protection trade to be made, we would be specifically accepting a lower level of protection to gain the mobility and load carriage, is this politically possible to do for a tracked vehicle?

You could choose any of the three options, each has a varying cost, capability, time to develop and risk.

The key to this is to…

- Go nowhere near putting a turret on it

- Keep it under ten tonnes with whatever protection can be extracted from that, minus a 2-3 tonne payload

- Make sure it can fit inside a container (Hi Cubes allowed)

- Hi mobility, tracks not wheels, emphasis on soft ground in Europe and the High North

- Provide options for making it uncrewed and using low-emission power and propulsion, big fleets and future-proofing

- Be LIS-compliant, and leverage as much onshore production and development as possible

UPDATE

A couple of interesting points from commenters and readers.

Is a 10-tonne limit a bit niche?

In the transportability section, I described the advantages of keeping to around 10 tonnes, especially for Chinook carriage as an underslung load. This is certainly a limiting factor and one might debate the trade-offs, but it would allow the vehicle to be used across a spectrum of operations that also included amphibious.

Another advantage of a 10-tonne limit is that it allows multiples to be carried neatly on C-130, A400M and C-17 aircraft, maximising efficiency.

For example, two would be possible on a C-130

On an A400M, three would be feasible, or two with a decent range.

See the diagram below for why 10 tonnes is a ‘sweet spot’

Why no BV206 Type Vehicles?

If those transportability benefits were not required, a larger vehicle would be possible.

I have deliberately ignored the Stormer chassis because it is heavier than 10 tonnes, and thus breaks a weight limit for Chinook, but if we were looking for an FV432 replacement, a modern-day Stormer might also not be a bad place to start.

In this case, a BV type articulated vehicle would also potentially meet the requirement

PS

The idea for calling it a modern Universal Carrier came from Paul B on X (formerly known as Twitter)

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks, TD. A most interesting article.

Top stuff

Excellent article. We had discussed on Twitter, so you know where I stand. Ref:

"It also requires a very specific mobility v protection trade to be made, we would be specifically accepting a lower level of protection in order to gain the mobility and load carriage, is this politically possible to do for a tracked vehicle?"

MRV-P was to be Stanag L2 based with aspiration of L3. A tracked MRV-P does not need to be any higher, but what if modern tech can get it to L4 with applique kits? Similar to JLTV A and B kit concept. If it has to go on a C130 or in a ISO container, then its rolling at base L3. If its rolling around Estonia, why not keep at B kit L4 all the time? Of course the caveat is that a B kit is not so heavy as to trash the mobility…..

Here is a thought on a similar vein- a Willys Jeep as used by the SAS in the desert weighed just over a ton carried 3 to 4 men and a twin and single machine gun. Top speed 65mph. A Jackal does about the same and weighs 6.5 tons! The Jackal is better protected but the smaller Jeep can go places a Jackal can't because of it's size, is a fraction of the price (even allowing for likely costs at todays prices) and at one 6th of the weight you can get a lot more of them transported whether in aircraft, helicopters or ISO containers. Don't get me wrong I would rather be in a Jackal in a war zone than a Jeep but if the powers that be can't deploy enough Jackals then I would prefer a Jeep to Shank's pony.

Not even a mention of the Bv206 or BvS10. Why?

Thought provoking stuff as ever TD.

It's kind of already covered by the "fit in a container" bit, but having a width less than 2.5m makes it compatible with standard vehicle regulations and consequently much easier to move around, since it's then not a "wide load"

If we are tight on width, it's worth noting that band tracks are very promising, but do tend to be wider than metal tracks for a given GVW. Similarly the light weight armour solutions out there do tend to have considerably greater volume than solid metal. There may ultimately be trade-offs between having a base vehicle that is easy to transport and appliqué systems that would need to be dismounted for transport.

Thinking on armour, matching the protection level to role seems important. A load carrier is likely to see small arms and artillery fragments at longer range, but shouldn't be getting close enough or be exposed enough that protection against AP ammunition at close range is required. Or is it? The artillery threat scales with the Stanag levels as well as the AP threat. Having a modular protection arrangement would allow trading the balance of payload and protection. Is mine protection a worry, or can we address that with the counter-acceleration rocket system? It might be possible to make the hull strong enough that it doesn't get broken but such a light vehicle will suffer from accelerations otherwise.

As for weapon mounts, the early versions of the GVA standard had a specification for a standard ring mount aperture, which might be an idea for attaching whatever it is you would like on top of the vehicle, be that an open weapon mount, a RWS with a hatch alongside, a cupola or a bunch of things I haven't thought of. That or have the roof plate easily customisable. I'm on board with "no turrets" to speed the development of the chassis, but I wouldn't want to be blind to ever fitting one.

Insightful and we never learn lessons from the past engineering marvels. A universal platform is affordable, economically sound, efficient, reliable and manufacturing sound. Why do we never listen.

I think an honoury shout out should go for a tracked vehicle that has not been mentioned, which is the Ripsaw. Originally conceived as a balls out fun recreational vehicle. It has been trialled as both a manned and unmanned vehicle. It can be outfitted as load carrier or with an unmanned turret. But crucially it weighs around 4100kg with a payload of around 1000kg. Its basic armour can withstand STANAG Level 3 and can be upgraded to Level 4. The basic manned version can carry a crew of 4. Which is be enough for a Javelin team, plus a number of carried reloads.

For a high mobility vehicle that is designed to get teams into an ambush position quickly, I can't think of a better vehicle.

Modern universal carrier, great post & good read, however you forgot the most important thing, civil servants & EU loving polotitions, they will never allow us to use British manufacturers Only EU probably German, so great idea, never happen, least with British manufacturers.

I'm not convinced that civil servants or politicians are the whole problem, since we also have media presence actively briefing against British companies on behalf of foreign companies.

Then you've got the BOAC problem where the requirements from the primary customer channel local designs into certain areas which are immediately thrown aside to buy from abroad.

The Ripsaw is worth a glance to get an idea of the art of the possible, but shot through with ITAR which is a massive headache, particularly if you want it as part of the Land Industrial Strategy.

The idea of racing into an ambush position seems like a bit of a tautology. Plus the 4 seater appears to be the civilian F4 – i.e. no armour at 4t. The armour to protect 4 guys to Stanag level 4 is likely to weigh a good bit more than half a tonne left over after 4 soldiers with kit get in.

This is a great idea as I think it is something UK PLC can actually deliver… and then enhance as time goes by.

An accessory? https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2015/7/1/2015july-its-time-for-a-direct-fire-breechloaded-mortar