A recent (and now closed) Request for Information (RFI) summarised the General Support Utility Programme (GSUP) requirement as…

The Army are seeking market information as to military light utility platforms as part of an initial scoping of options to replace Land Rover and other similar vehicles as part of the General Support Utility Platform Programme. Companies are invited to provide information on current and developing military utility platforms. Variants of interest include General Support, Ambulance and Fitted for Radio particularly when these are all included within the same vehicle family. Platforms should be no more than 3.5T and be driven on Cat B license (potentially less ambulance variant).

Although the RFI has closed, and as we have seen from DVD2022, several contenders have emerged, this article will examine the options.

Land Rover Replacement History

There is always a history.

90 and 110 Land Rover Defenders entered service with the British Army in 1985, mostly in General Service and Fitted for Radio variants. Specialist types entered service soon after; ambulance, Snatch, V8 GS, Rapier towing and special forces.

On April 1st, 1997, the first Defender XD Wolf (Truck Utility Light High Specification / Truck Utility Medium High Specification) entered service, with the 300TDi engine and an entirely new design from the 90/110s.

All of them were in service by the end of 1998 (they didn’t mess around then!).

The final quantity of the XD Wolf was;

- 1,411 TUL (Short Wheelbase)

- 6,514 TUM (Long Wheelbase)

The General Utility Support Programme (GSUP) can reasonably trace its roots back to the Operational Utility Vehicle System (OUVS) programme from 2003.

Click to read a long form post on OUVS

The programme was launched in early 2003, announced at the Defence Vehicle Dynamics (DVD) show by Lord Bach in the same year.

MRV-P was an entirely different programme (and one I have written about several times) with diverse requirements, principally in the protection area. As we have seen from DVD 2022, the MRV-P has now also ceased, with the requirements being redefined.

OUVS merged into MRV-P resulting in no firm orders or any vehicles entering service, and so back to General Utility Support Programme (GSUP), or OUVS in old money.

Full circle, 2003 OUVS (via 2012 MRV-P) is now 2022 GSUP

Sadly, OUVS and MRV-P are yet more examples of the British Army unable to articulate a set of requirements and stick with them.

Industry and public funds have been wasted, two decades have flown by.

It remains to be seen if GSUP will go the way of OUVS.

Land Rover Replacement — General Support Utility Programme (GSUP)

Not a great deal has been released by the MoD about the General Support Utility Programme (GSUP), the RFI is an early-stage scoping activity, and there is some distance to go before firm user requirements are defined.

What can we deduce from…

Land Rover and other similar vehicles.

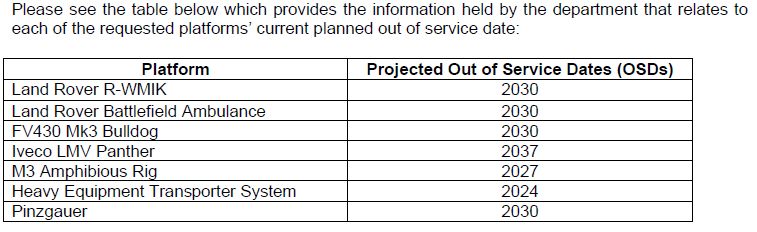

A recent FOI request revealed the out-of-service date for Land Rover and Pinzguaer.

The RFI also stated…

Variants of interest include General Support, Ambulance and Fitted for Radio, particularly when these are all included within the same vehicle family.

It should be noted that Pinzgauer, Land Rover R-WMIK and Land Rover Battlefield Ambulance all have an Out of Service Date of 2030, but in the table above, Duro and other Land Rover variants are not listed.

A recent contract award revealed 65 variants of Land Rover and 31 Pinzgauer variants are in service.

The Conventional Vehicle Systems (CVS) Post Design Services (PDS) Design Authority (DA) contract will commence on 1st September 2022 and is to run for 3 years and 7 months, with an additional 4 +1 option years to extend the period of the service.

This contract applies to all platforms listed below:

Platform: Land Rover Wolf, Variant: 65, Fleet size: 6410

Platform: Pinzgauer, Variant: 31, Fleet size: 873

Platform: Snatch 2b, Variant: 1, Fleet size: 20

Platform: RWMIK, Variant: 1, Fleet size: 187

Platform: Trailer Lightweight, Variant: 1, Fleet size: 7837

Accepting that the MoD is at a very early stage of concept definition, this article assumes GSUP will include all variants of Pinzgauer, Duro, and Land Rover.

Many of the 90s have been disposed of as they are unsuited to carrying BOWMAN.

By 2030, even the youngest Land Rover in the British Army will be three decades old, having given excellent service.

Click to read more (affiliate link)

Roles, Requirements, and Users

OUVS was tri-service, GSUP appears at first glance not to be, the RFI stating that it is for the Army.

It is wise not to read too much into this, but it would be an interesting diversion if the other services tendered their utility vehicle replacement.

I will not list all those 65 roles and 31 variants as many will likely include winterised and waterproof versions, different equipment fits and shelter designs, but some typical models are shown below.

Short wheelbase (TUL) – Hard Top

Short Wheelbase (TUL) – Soft Top

Long wheelbase (TUM) – Hard Top (including Fitted for Radio (FFR))

Long wheelbase (TUM) – Soft Top

Long wheelbase (TUM) – Station Wagon

Long wheelbase – Battlefield Ambulance

Long Wheelbase — Weapons Mount Installation Kit (WMIK)

The WMIK has an equally complex history, with Refurbished (R-WMIK) and R-WMIK+ variants in service with Light Cavalry and airborne units.

The original Truck Utility Heavy (TUH) Defender XD was dropped in favour of the RB44, but after this was withdrawn, the Pinzgauer was used in its place.

Pinzgauer also replaced the 1-tonne Land Rover Forward Control.

Specialist variants such as the Watchkeeper support vehicle or Light Role NBC will likely be within scope.

Click to read more

It is also not certain if any of the specialist Duro vehicles are within scope.

There are more roles and variants for GSUP than any other vehicle programme.

It also appears that none of the GSUP vehicles is protected, beyond the basics, and maybe that is a good thing, it creates clear role delineation, drives down weight and cost, and allows maximum commercial design exploitation.

The successor to MRV-P will cover any protected vehicles by the look of it, with clear blue water between that and GSUP.

This is a Good ThingTM

Weights and Dimensions

Although the roles might be numerous, defining the constraining weights and dimensions is probably easier to articulate, although the publicly available RFI extract does seem relatively vague (the detailed RFI is clearer)

OUVS had two clear weight classes, based on payload. OUVS (Small) at 2–3 tonnes and OUVS (Large) at 4–5 tonnes

This makes perfect sense, the OUVS operational analysis being perfectly valid.

With nothing between a Land Rover and MAN SV, I think we miss the RB44, well, at least the potential offered by the RB44, not the vehicle itself.

Maximum weights are also important because they influence the category of licence to drive them. Driving licences require management and training, they are an important issue for the British Army. Although some slightly different rules for those who passed their driving test before 1997, the rules are below.

Car

B: Qualifies a person to drive a vehicle with a Maximum Authorised Mass (MAM) of up to 3,500 kg with up to eight passenger seats and with a trailer of up to 750 kg MAM.

BE Qualifies a person to drive a vehicle with a Maximum Authorised Mass (MAM) of up to 3,500 kg with a trailer, and if the person qualified after 2013, tow a trailer that weighs up to 3,500 kg MAM (with a maximum width of 2.55m and length of 7m)

Medium Size Vehicles

C1: Qualifies a person to drive vehicles between 3,500 and 7,500 kg MAM (with a trailer up to 750 kg). This is the most popular licence in the UK for commercial vehicles,

C1E: Drive C1 category vehicles with a trailer over 750 kg. The combined MAM of both cannot exceed 12,000 kg. Although this is less common, it allows heavier trailers to be towed than a C1.

Large Vehicles

C: Vehicles over 3,500 tonnes with a trailer up to 750 kg

CE: This used to be called the Class 1 licence, essentially for large articulated trucks. It allows the person to drive a Class C vehicle with a trailer of over 750 kg

And this is before we get into passenger-carrying vehicles, hazardous cargo and other regulation and licencing issues. On top of this, the Army will overlay training and authorisation for specific vehicles (or types of vehicles) within the fleet.

It is tremendously complicated and can have significant cost implications.

When I wrote about vehicle transportability recently, I concluded there are several breakpoints for vehicles, dictated by everything from weight to helicopter sling loading. Licences were included in these breakpoints.

Towing capacity is also important for GSUP vehicles.

My Thoughts on Meeting GSUP Requirements — Replacing the Land Rover

General Support Utility Vehicles and the GSUP programme are certainly more complex than meets the eye, the sheer number of variants and roles demonstrates this.

My thinking goes something like this;

- Maximise ‘White Fleet’

- Can we refurbish?

- Be Pragmatic about Vehicle Weights

- Recognise the importance of LIS, Net Zero and Levelling Up

- Options

- Expand

Maximise the White Fleet (in Green)

The MoD outsources management of the non-operational fleet of cars, vans, trucks and specialist vehicles to Babcock under the Phoenix II contract.

I think this is due for recompete this year.

The Military Provost and Guard Service use Ford Ranger XL pickup trucks.

We already have a mature contract and experience with utility vehicles provisioned through lease partners, so why not just do more?

The cost profile would have to account for different treatment profiles, need some off-road recovery provision and likely replacements’ frequency more than usual.

The British Army has many calls on a finite budget, we all understand just how much of its equipment is obsolete, if we can provide more general support vehicles through a lease and fleet management approach, this might release more budget for more pressing matters.

Is Refurbishment an Option?

Can we keep the existing fleet in service beyond 2030?

The basic technical requirements for GSUP are mostly the same as what we have now, there are no great leaps forward planned.

There is an active after-market for Land Rover Defenders in the UK and abroad, many components are available as refurbished, and importantly, even manufactured new. Hobson Industries, Richards Chassis, and Bowler Motors, to name but three, and there are others.

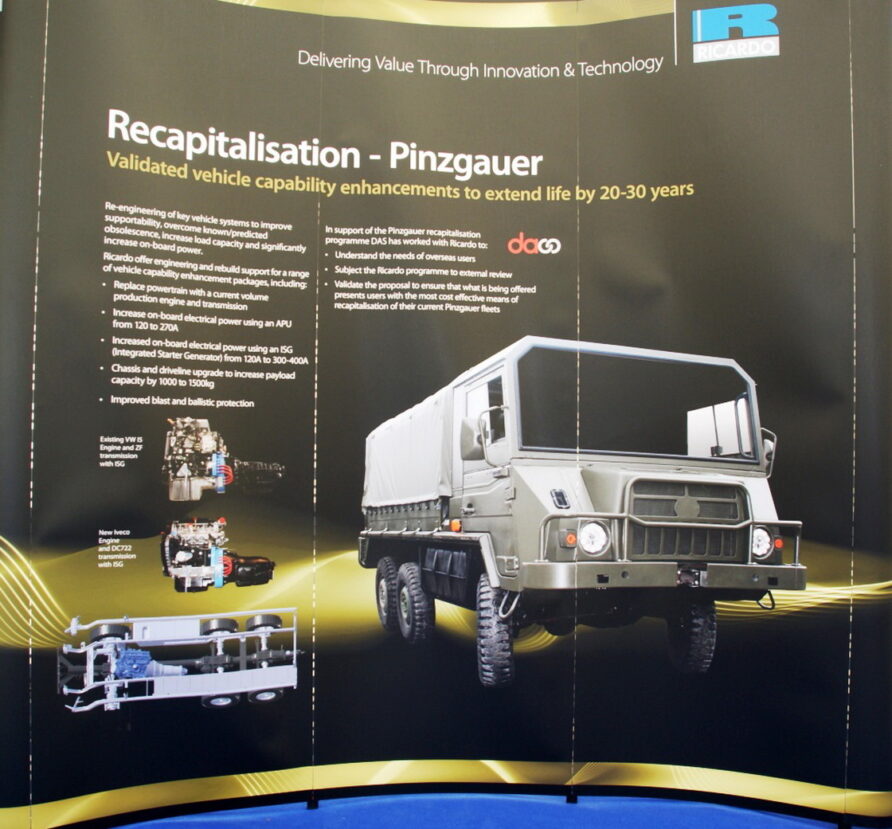

A few years ago, Ricardo also proposed a refurbishment of the existing Pinzgauer fleet.

As mentioned above, the fleet of both Land Rover and Pinzgauer vehicles is hardly new, but if there is an option to eke out yet more life from them, then we should at least examine it.

A 5-year contract to add 10 more years, perhaps.

One could easily see a veteran-owned/staffed business together with Babcock.

It would also support wider governmental objectives on the skills agenda and regional levelling up.

Refurbishment might also decrease the support and logistics impact compared to a wholly new vehicle, these are important considerations.

Pragmatism on Vehicle Weight

How much militarily useful payload can a 3.5-tonne vehicle carry?

Low vehicle weights can be important for some roles, especially those reliant on small aircraft and helicopters, but these seem to be moving to increasingly specialised vehicles.

If a vehicle is to be carried by helicopters, then I would propose they be a separate category.

If all we are doing is giving the QM a means of moving rations on a range day, see my point on White Fleet.

The weight and trailer weight issues are important because they will influence the total cost of ownership of any given vehicle fleet, but it might not be as simple as we think. Keeping a vehicle under 3.5 tonnes will mean fewer C1 licences overall, but might mean more actual vehicles because of payload requirements.

Every single vehicle in the system needs qualification, inspection, and maintenance.

Artificially keeping under 3.5 tonnes to save on licences could be a false economy, the same with trailers. Although using trailers to squeeze extra payload out of a BE licence is fair enough, trailers are another piece of equipment on JAMES, subject to inspection and maintenance requirements like other vehicles. Nothing is free, and trailers can impact mobility.

As the Army moves to heavier protected vehicles, it might be more practical to mandate C1 qualification at Phase 2 training for everyone. This is more challenging for the Army Reserve, no doubt.

The ambulance and WMIK variants are likely to be over 3.5 tonnes anyway, for the General Support Vehicle we have to recognise the limitations of requiring vehicles to be under that weight.

For these reasons, I would propose a less rigid approach to vehicle weight, accepting that fewer but larger vehicles might be a better route.

The Importance of the Land Industrial Strategy, Net Zero and Levelling Up

We cannot ignore them, simply put.

GSUP should be aligned with the Land Industrial Strategy, Integrated Operating Concept and national objectives, and for me at least, this means…

Be markedly less dependent on fossil fuels

The MoD has funded research into hybrid vehicles for over two decades, back to TRACER and QinetiQ HED in the late nineties.

The latest is the £63million Protected Mobility Engineering & Technical Support (PMETS) contract which has demonstrated the latest hybrid technology on a Foxhound, Jackal, ATMP and others, together with Magtec and NP Aerospace

It needs to move beyond trials and into production.

Given the lower weights involved and proximity to commercial systems, one would imagine GSUP offers a lower-risk means of moving into implementation. Using GSUP to support the broader national and defence effort in this area would make perfect sense, maybe not straight away but as part of a development spiral.

This is a good background article on the British Army’s approach to emission reduction.

Levelling Up is a ‘whole of government’ initiative to improve the economic fortunes and well-being of all parts of the UK, especially the English Regions and devolved nations. Like many such initiatives, it can mean different things to different people, but there is no doubt about the seriousness that this government places on it and the financial backing it is providing.

The Government has also committed to double research and development investment with a target of spending 2.4% of GDP on public and private R&D by 2027. Some of this R&D will contribute to the now legally enshrined ‘Net-Zero by 2050’ objective.

Government-supported initiatives include the National Productivity Investment Fund, Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund and the Strength in Places Fund.

The Land Industrial Strategy (LIS) describes the Government’s approach to industrial matters;

An innovative, globally competitive, and highly skilled sector in the UK that can develop, deliver, and sustain the capabilities we need in the land domain, collaborate domestically and internationally on key defence projects, export overseas, and contribute to our national prosperity.

This does not mean the MoD will purchase every item of equipment from UK suppliers but sets out some broad ways of working to achieve the objectives.

- A strategic approach to acquisition that incorporates a wider definition of national value, including Operational Independence and Social Value

- A longer-term approach to investment and partnering that increases confidence in the UK’s investment pipeline and provides stability needed to invest in new technologies and skills;

- An enhanced approach to portfolio management to create a steadier drumbeat of investment, with

an increasing focus on mission systems, where cost-effective to do so; and - A more collaborative approach between MOD and industry, based on cooperative and transparent cultures and behaviours

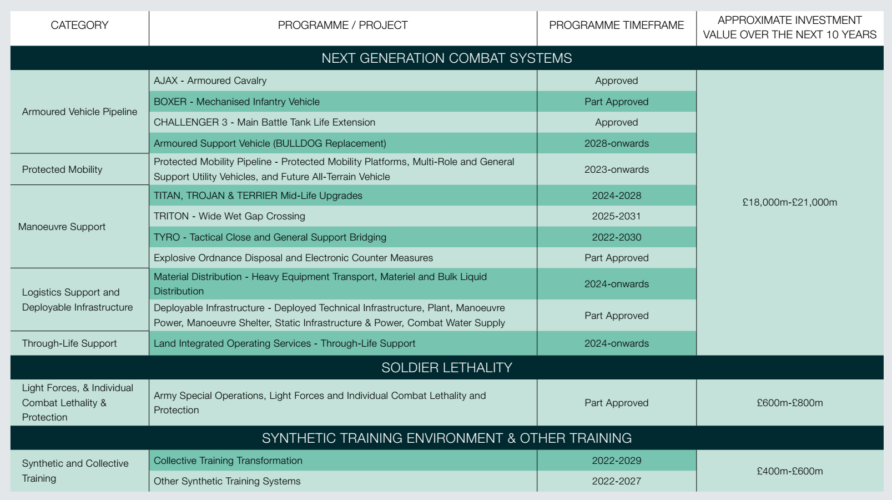

General Support Utility Vehicles are included within the Protected Mobility category

The LIS is an excellent document, not least because there is a recognition of past problems.

The Land Industrial Strategy, Levelling Up and Net Zero are intrinsically linked, the MoD cannot ignore this in any of its equipment programmes, and GSUP is no exception.

Land Rover Replacement Options

You could throw a stick at any country, and it would land on a contract to replace legacy 4×4s with a modified SUV or pickup truck.

SUV and Pickup Truck Derived Vehicles

All might have additional power generation capacity, convoy lights and a NATO standard towing pintle, but they are more or less civilian designs, with green paint.

SUV-derived options include G-Class, Land Rover Defender, Ineos Grenadier, Volkswagen Amarok and Jeep J8s, there are plenty of donor vehicles to choose from.

A guest author (Andrew B) wrote an article last year that looked at some of these, concluding that whilst the new Defender and Grenadier had some merit, the G-Class from Mercedes-Benz would be difficult to beat.

The image below shows a Rheinmetall Caracal, based on the G-Class 464 series chassis.

The SUV market has undoubtedly moved to the higher-cost luxury market, leaving many traditional Defender owners with no other practical options but to look at pickup trucks from Nissan, Ford, Toyota, and Isuzu.

Electronic driving aids and their mobility cannot be doubted, but this comes at a cost.

Supacat has partnered with Jeep for the GSUP requirement after previous attempts to offer a Land Rover Discovery-based Light Role Vehicle.

The J8 is 4850 mm (L) x 1877 mm (W) x 1995 mm (H), Weighs (GVW) 3200 kg and has a payload of 1000 kg and towing weight (braked) of 2495 kg.

Based on the Jeep Wrangler JK platform, it is assembled in Gibraltar by AADS

Looking further afield (and not strictly SUV-derived), Eurovesa in Spain offers the Vamtac LTV

Worth a look?

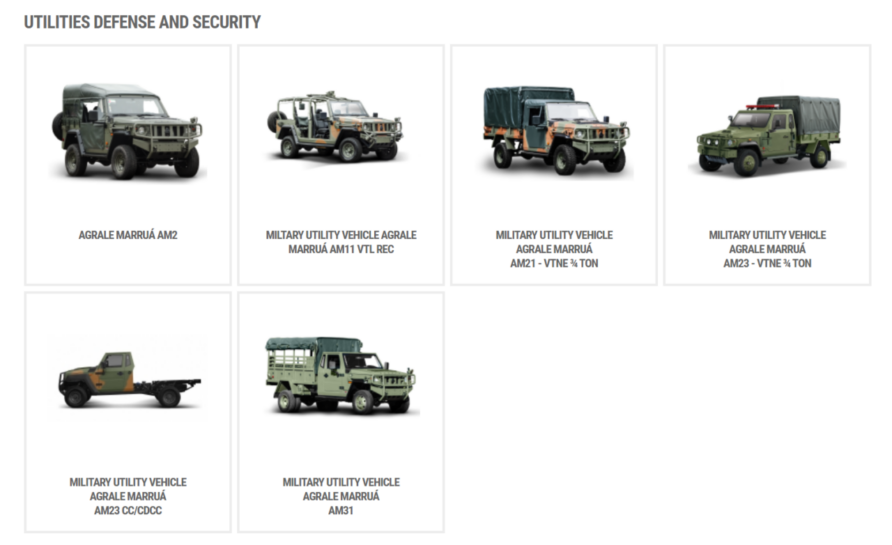

Agrale from Brazil also has a good range of utility vehicles.

France has introduced the Ford Everest-based VT4 Trapper (in two versions) from Arquus

The Netherlands, same route, different vehicle; Volkswagen Amarok.

Glomex Military Supplies from the Czech Republic recently won an order for 1,200 modified Toyota Hilux vehicles, and in Finland, something similar using a local integrator called TruckMasters.

A couple of years ago, the RAC went for a large fleet of Isuzu D-Max pickup trucks, this type of vehicle is becoming increasingly common in the UK among large fleet buyers.

Each will be equipped with an innovative All-Wheels-Up recovery system.

There are several integrators such as Pickup Systems that offer drop-in bodies.

The two main alternative providers for pickup truck-derived military utility vehicles for the UK are Jankel and Ricardo.

Ricardo developed a Ford Ranger T6-derived military pickup in 2019

The general service Ranger concept created by Ricardo is intended to be available with a range of powertrain options, including Ford’s powerful and refined 213 PS 2.0-litre EcoBlue Bi-turbo diesel powertrain, which produces 500 Nm of torque for excellent load-hauling capability. This is mated to an advanced new 10-speed automatic transmission for easy, economical driving. Key features of the adaptation designed by Ricardo include options for a rollover protection system; a ring mounted weapon system, similar to that used in the WMIK; an armoured ballistic underfloor and armoured glass; lightweight but heavy-duty front and rear bumpers; skid plates for the radiator, powertrain and fuel tank; rock sliders and improved wading/fording protection; NATO IRR paint/camouflage and 4-point seat harnesses. In addition, the 24V electrical system is enhanced to provide the power requirements and EMC protection expected of modern defence vehicle applications, and the chassis can be equipped with upgraded springs, dampers, brakes, heavy-duty wheels and all-terrain tyres, offering greater ride height and more versatile towing capacity. In delivering this project Ricardo has worked closely with Polaris Government and Defense, in particular for support in the areas of onboard power management and C4i (command, control, communications, computers and intelligence) integration.

One would expect Ricardo to offer something very similar for GSUP

Another strong contender is Jankel, a company with a long pedigree offering pickup-derived military vehicles.

Jankel offers four vehicles based on the Land Cruiser or Hi-Lux platforms in two or three-axle variants, with the FOX Rapid Reaction Vehicle in service with Belgian special forces.

As can be seen from the video, Jankel also offers a larger vehicle range based on the Mercedes-Benz Unimog platform.

If the requirement leads to crossing the 3.5-tonne threshold, an alternative to simply using a different vehicle (like the Jankel Unimog for example), is to convert to a 6×6 configuration or add an extra non-driven axle. These conversions are commonplace in Australia and with our increasingly close defence relationship, something that could be leveraged.

A good example of this is a company called Australian Patrol Vehicles

There is also a company in the UK doing similar things (and I wonder if there is a commercial relationship), called Prospeed Motorsport, marketing as 6×6 Hiload.

They take a standard Toyota Hilux, change the chassis and add a driven axle to create a larger payload area and to increase the payload to 3 tonnes, with a gross vehicle weight of 5.6 tonnes.

Prospeed has made several variants and proposed others.

Any one of these would be a viable option, they are low-risk, and we would be joining a big club of users and tapping into global supply chains to reduce support costs.

Ricardo has more recently shown an additional axle option called HEX

HEX uses a hybrid drivetrain.

An electric rear drive system has been adopted that uses a production Ford drive unit to provide up to an additional 210kW of power, over and above the class leading 186kW of power from the existing 3.0L V6 diesel engine. The De Dion rear suspension design is not only weight efficient and robust but also provides better wheel control for improved traction and ride. In addition, the De Dion arrangement decouples the suspension and drive systems to allow a range of drive units to be used or deleted for a cost-effective 6×4 variant with maximum payload using an undriven ‘lazy’ axle.

Definitely an interesting option.

Ibex or Fering

If we wanted to take a little more risk but maximise UK industry involvement, Net Zero and skills development, there is another option.

Sitting in the Land Rover after market sector is a few SME manufacturers of off-road sports and commercial vehicles that would offer options for a maximal approach to the Land Industrial Strategy.

Ibex Vehicles are made in Sheffield, with a constantly evolving design that has stood the test of time. Some of their vehicles are still in service 30 years after being purchased and used continuously.

They are available in several variants, from short wheelbase to two-seaters and longer wheelbase variants.

An extra long wheelbase and 6×6 version are also in service

Although no ambulance variant exists, it is certainly possible to see the design adapted to suit a box body for the FFR and Ambulance GSUP requirements.

The design is extremely flexible and can use component sets from the global volume market, an important consideration for vehicles that will be used overseas.

It is simple, rugged and built with commercial or agricultural use in mind. The image below shows an extended 2+2 chassis cab model.

Its rear ladder frame section provides a mounting plane for rear-mounted bodies, and it has an enlarged 270ltr fuel capacity, air suspension, remote reservoir shocks, diff locks, super heavy-duty axles and drivetrain, full underbody protection and body armour, stealth-mounted winch and pre-filtered raised air intake

There is an elephant in the room, Ibex is an SME and doesn’t produce vehicles at the volumes required.

DML and Supacat manufacturing a couple of hundred Jackals is relatively different to manufacturing thousands of Ibex vehicles, but are we in a rush? Again, we could create a separate commercial entity to maximise skills development, apprenticeships and veteran opportunities.

They are easy to dismiss, but I quite like it, and there is even a transition to an electric version, the Munro.

Although, Munro and Ibex are not connected in any commercial capacity.

This brings me to another option, the Fering Pioneer.

Whilst Ibex has been going for decades and has a very mature design, Fering is mostly new on the scene.

The vehicle has been designed, developed and tested from the ground up with every aspect of the car delivering utilitarian use. This is your next ‘go anywhere, anytime’ vehicle which allows you to explore the deserts of Africa one week and the snow drifts of the Arctic circle the next.

It uses modular construction and a range of power options, with payloads of up to 1.5 tonnes whilst still having a kerb weight of only 1.5 tonnes.

Could it scale to support the ambulance requirement, is it too immature, and would it be too high a risk?

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Industrial and Van Derived Vehicles

Whilst we can all probably see that SUV and Pickup truck-derived military vehicles are increasingly common, a less explored option is the industrial utility or van-derived vehicle.

The Hako Multicar M31 4×4 has a maximum allowable mass of 5.6 Tonnes with a payload of 3 tonnes and can tow 3.5 tonnes.

The Multicar is the base vehicle for the KMW Mungo, in service with the Heer.

The KMW Mungo ESK variant has a maximum weight of 5.9 tonnes and can carry 10 personnel and their equipment to a total distance of 500 km with a top speed of 90kph. Designed for carrying cargo, the Multi-Purpose Vehicle has a payload of 1.5 tonnes and uses a skip loader rather than a hook lift to reduce height.

Whilst these are specialist vehicles in service with the German armed forces, they would also make a practical utility vehicle, the M31 is 300 mm shorter than the Defender.

There are plenty of other examples of small agricultural and municipal vehicles from European manufacturers.

The permanent 4-wheel drive Aebi MT760 has a payload of 3.5 tonnes with a maximum vehicle weight of 6.5 tonnes, and can also tow a trailer weighing 3.5 tonnes.

The Unitrac 112, has slightly higher specifications, 5.07m long, 2.08m wide and 2.47m high. With an empty weight of 3,475 kg, it has a maximum payload of just over 6,000kgs.

It can also tow a maximum weight of 10,000 kg.

But within the same general footprint of these industrial vehicle types

It also has several hydraulic tool attachment points, four-wheel steering, a Perkins diesel engine and can have a tipper body fitted. An interesting feature of the Unitrac is its ability to quickly demount its load bed, like a European swap body container.

It would be easy to see this feature exploited in multiple logistics, communications, command posts, weapon carriers, and combat engineering roles.

The Mercedes Sprinter, Iveco Daily and Volkswagen Crafter are obtainable in factory-fit all-wheel-drive versions. Third-party integrators also extend this to other manufacturers.

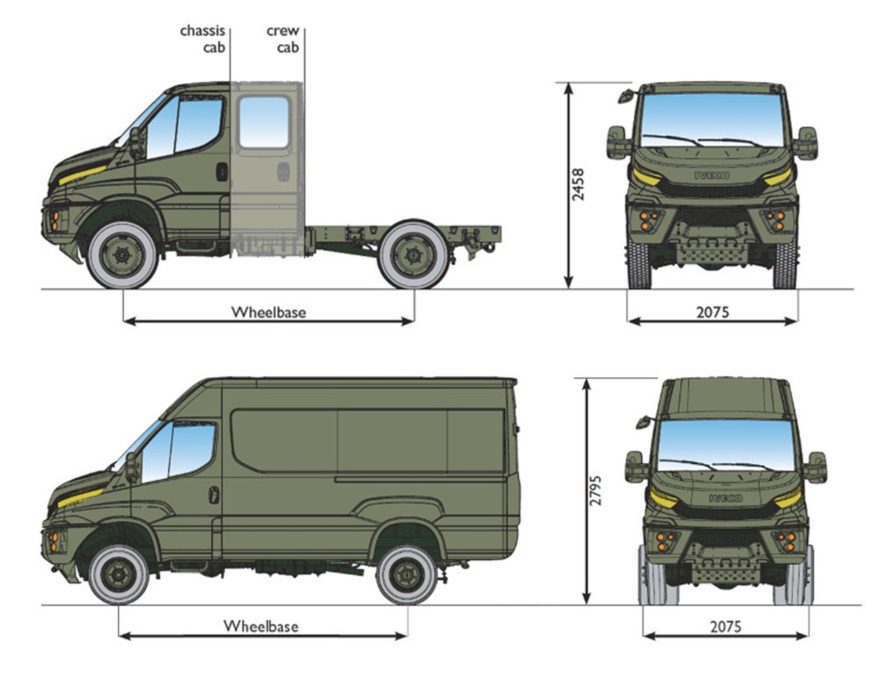

The Iveco Daily 4×4 is available in van, crew and chassis cab models, each only 200 mm longer than a Defender.

Derived from the Daily 4×4, the Military Utility Vehicle (MUV) is available in several cab configurations and even a minibus.

Depending on configuration gross vehicle weight can be up to 7 tonnes, with a 4-tonne payload. The vehicles all have blackout lighting, NATO standard towing facilities, night vision-compatible instruments and other military features.

The Dutch company DMV also uses the Iveco Daily platform, the latest version being the Anaconda, entering service with the Royal Netherlands Korps Mariniers.

Other commercial vehicle-derived designs are from Auchleitner in Austria, the Mantra 4×4 and Carrier 4×4.

These are in the same weight and payload class as the Daily 4×4 and MUV.

Torsus in the Czech Republic also makes capable off-road utility and passenger-carrying vehicles.

The minibus models got me thinking about mobility for a typical light-role infantry company.

With a pickup truck design, a company of 150 personnel would require over 35 such vehicles and drivers. Each would have an entry on JAMES generate maintenance and inspection burdens significantly more than currently. But, it could all be done on a Category Licence (except the ambulance and any other heavier variants)

Move the dial to something like an Iveco MUV, Torsus Terrastorm, or Achleitner Carrier and yes, you would need C1 licences (and possibly PSV also), you would only need 10 vehicles and drivers, plus maybe two or three more for cargo, and the specialised variants.

By thinking differently about licences, we might be able to provide significantly enhanced mobility and capability for those units traditionally without.

One of the most common uses for a Land Rover Defender 110 is with the Fitted For Radio variant, as a Squadron or Battery command post.

At best, the interior volume of an FFR 110 is 2m3

So, we are forced to pitch a 9×9 tent off the back of it to generate a working room for the CP team.

Occasionally, we back-to-back vehicles.

The tent is carried in a trailer, of course.

Imagine a larger vehicle.

Not only do you save time and improve agility (and thus survivability), but you also create a much more efficient and ergonomically working space.

The short wheelbase Daily 4×4 has a usable interior volume of 12m3, 10 more than an FFR, and not much less than an FFR with a 9×9 tent. Oh, and no trailer.

Command on the move.

Expand

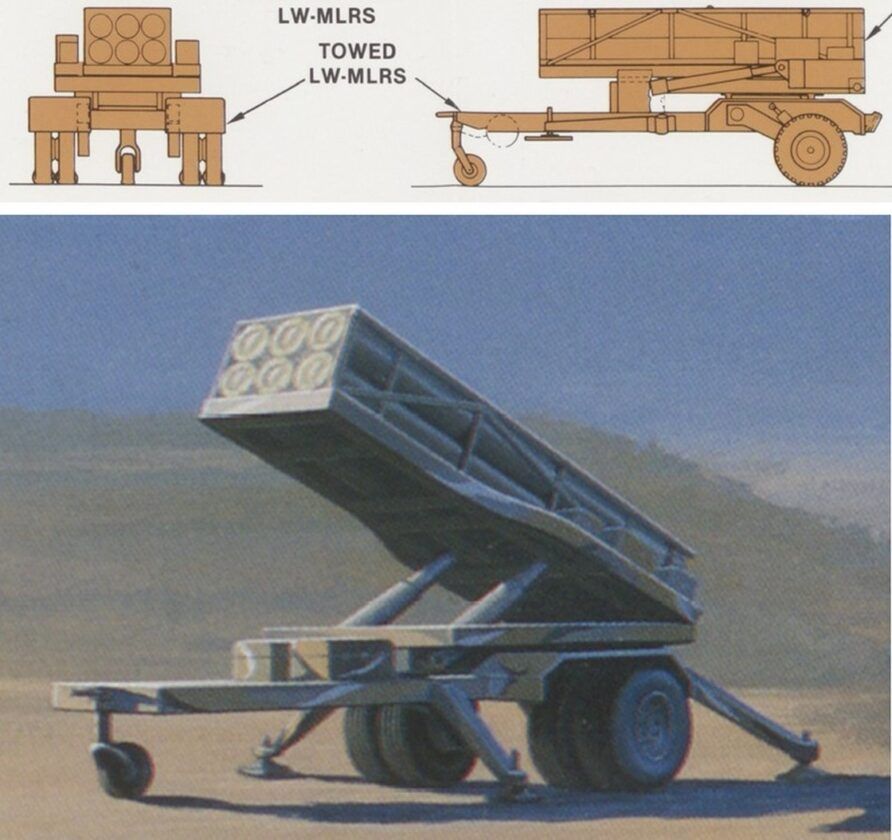

With a vehicle selected (and any of the options above would be good), it is not beyond the imagination to envisage how they could be expanded to light cavalry, artillery, or combat engineering roles.

Some of these are obvious.

Some less so

Final Thoughts on Replacing the Land Rover (and Pinzgauer)

All the options above would be good, all will have some UK industrial benefits, some might be obvious, others less so, but the MoD and British Army, after several failed attempts, should be thinking about risk reduction.

Risk reduction is not just about the programme itself, the British Army is already heavily exposed to Rheinmetall and KMW, and it would be wise not to increase that exposure.

That would require some decision-making out of the programme, perhaps at the ministerial level.

Whilst GSUP is notionally limited to 3.5 tonnes, there is a recognition that for some roles, such as ambulance and light gun towing, that will need to increase.

It would therefore make sense that whatever is chosen for GSUP has options for higher weights (and probably an extra axle) without requiring a separate vehicle.

While I favour IBEX, being realistic about risk probably excludes this option, leaving two design choices.

- Engine front pick-up derived (Ford, Isuzu, Toyota) using UK integrators to add additional military features

- Cab over engine van derived vehicles like the Iveco Daily

Either of these approaches would deliver capable vehicles at low-risk and reasonable cost, and that exploit large and global supply chains.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hybid drive vehicles have some obvious benefits but also the obvious drawback that most of the world’s lithium needed for the batteries comes via China. No point in escaping dependence on fossil fuels only to replace it with dependence on lithium.

Excellent read. Thank you for posting!

That was my FOI not a parliamentary answer.

Ah, cheers, will correct

An excellent overview, thank you. There are some very interesting options from eastern Europe – Poland, Serbia and so on, including Turkey and Greece – that would presumably offer “better” prices and more scope for local manufacture(?)

@Bloke down the pub

Several gigafactories are being built in the uK to make EV batteries.

But the UK is also quite literally swimming in Lithium…ts a byproduct from Geothermal energy…

See:

https://cornishlithium.com/projects/lithium-in-geothermal-waters/#:~:text=The%20granite%20rocks%20that%20underlie,permeable%20geological%20faults%20at%20depth.

That is without doubt the best and most comprehensive article I have ever come across on this subject, a subject I have been in and out of for 20 years.

And now with HILOAD, which is 4×4 or 6×6 very much getting into the mix.

http://www.6x6hiload.co.uk

Would a lot of the driver licensing bottleneck not disappear if the UK woke up and realised Brexit has happened, and it is no longer necessary to stick to the EU's nonsense 3500kg MAM for a basic "car" license? Revert back to the pre-1997 7500kg MAM weight on a car license and problem solved. Even the Australians can drive 4500kg MAM weight on a car license. With modern brakes and modern tires, why limit car drivers to 3500kg? Could it be nanny-statism, perhaps?